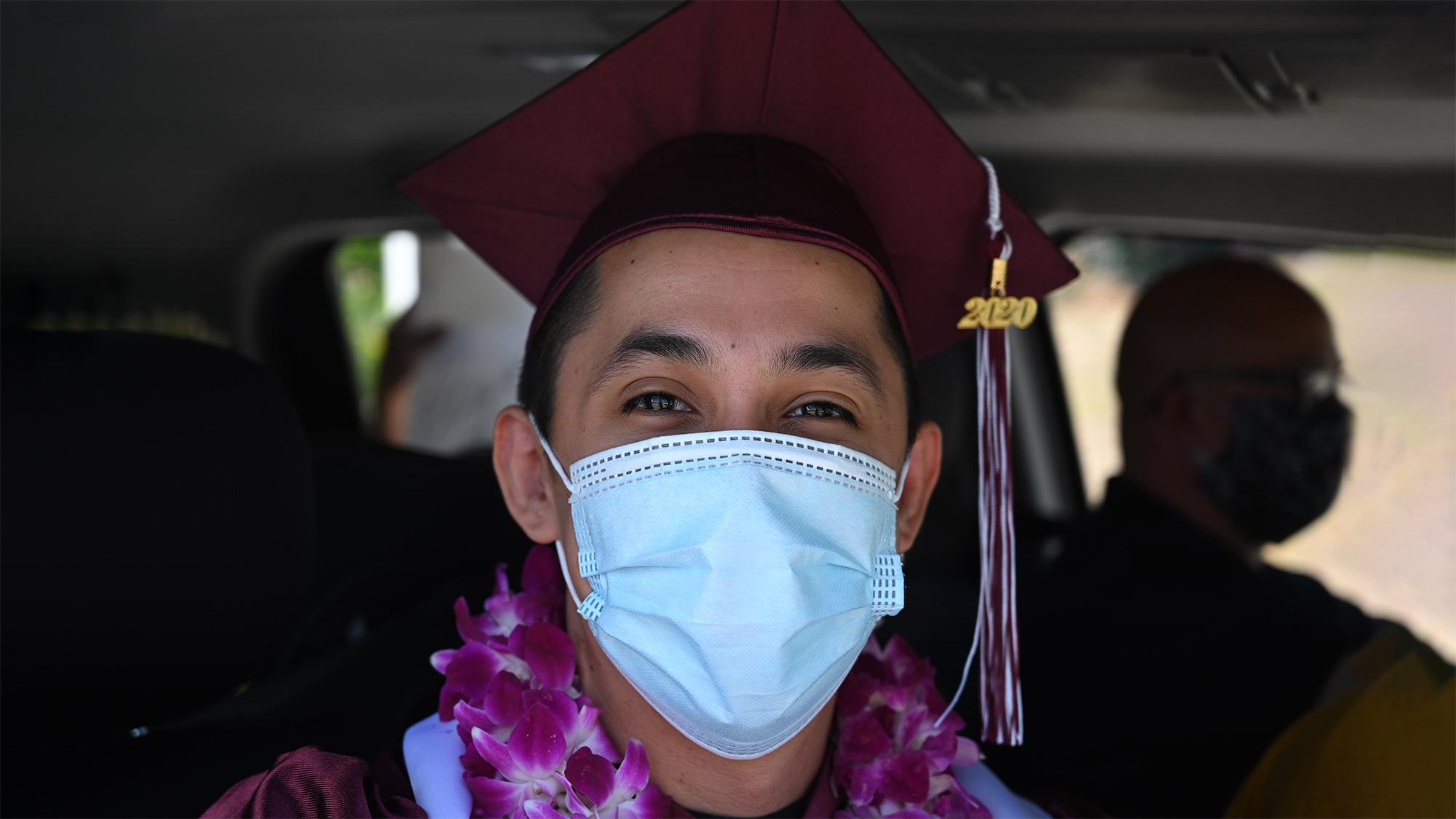

The coronavirus pandemic has changed the student experience. What next?

- Cheating increased during remote learning in 2020, spurred in large part by homework assistant services like Chegg.

- Isolated and lacking support, many students turned to homework assistant programs to offset their stress and anxiety.

- Universities need to reexamine the traditional student experience, while edtech must reconsider their services in light of student needs.

It’s hardly a newsworthy take to say the coronavirus pandemic changed the relationship between customers and industry. During its numerous and patchwork lockdowns, people lost access to businesses the way they once did, forcing those businesses to hastily adopt new strategies to meet ever-evolving needs and regulations.

While challenging all around, some industries managed these changes more adroitly. Retail accelerated its direct-to-consumer advertising, embraced digital engagement, and shifted in-store experiences to focus on safety and care. These strategies have proven so popular that they’ll likely become standard offerings moving forward.

The same can’t be said for every industry. Those unable to adapt or who viewed themselves as bulwarked against disruption continue to struggle as the pandemic endgame stretches on.

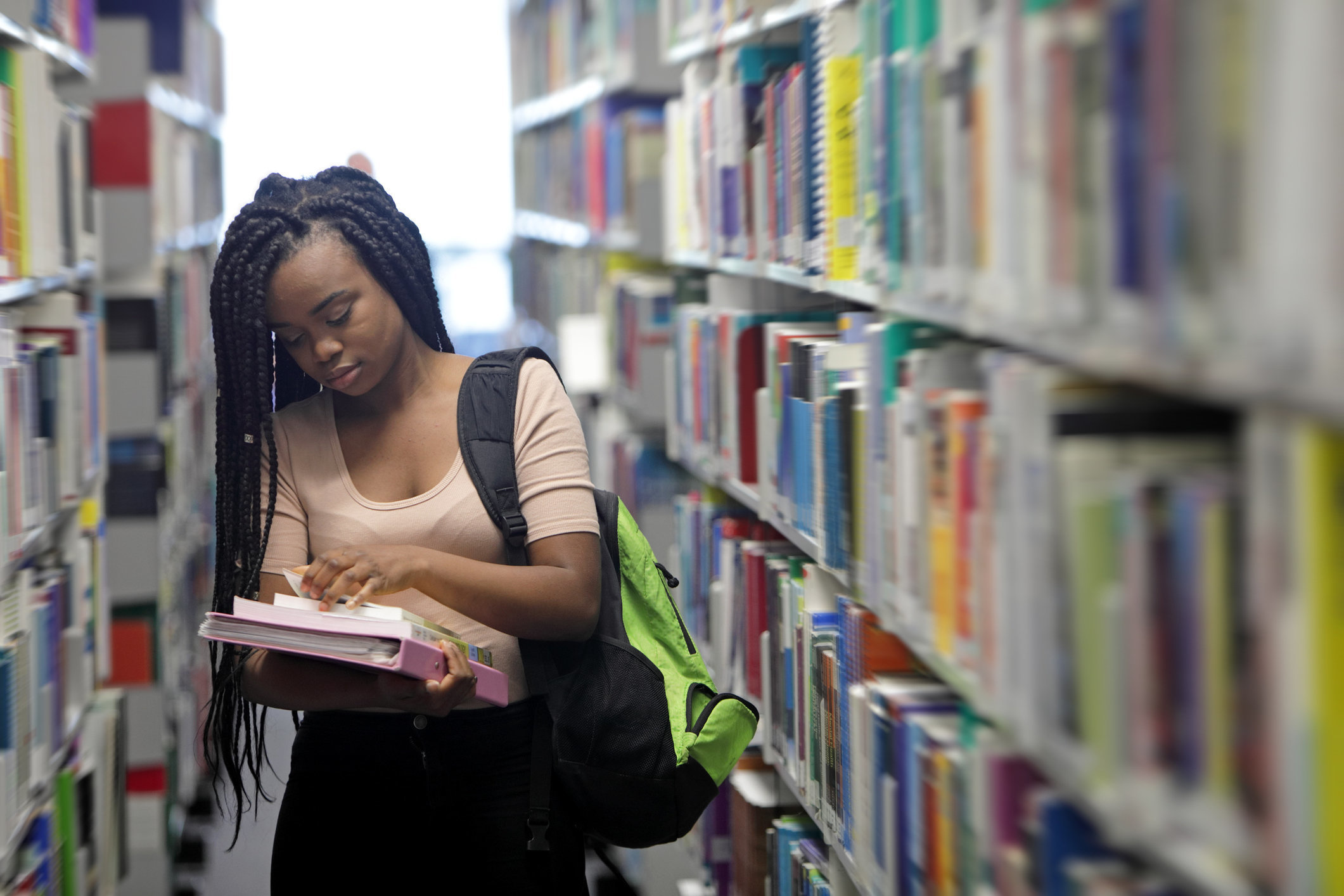

Take higher education, a notoriously entrenched industry. Before the pandemic, online learning was traditionally viewed as a stopgap measure for adult and so-called “nontraditional” students. That lack of commitment left colleges and universities less prepared than they may have been for the mass exodus of winter 2020. Many teachers had not developed lesson plans suitable for the online model. Academic resources remained campus-bound or anemic in their virtual states. And far too many students found their online access unreliable.

As higher education attempted to install new teaching practices in real-time, students began feeling increasingly isolated with unfulfilled needs—needs the business world was happy to provide quickly and efficiently. Unfortunately, business incentives can often lead companies to confuse consumer needs with their desire for ease. As more companies squeeze into the education space and the pandemic’s lasting effects become realized, finding ways to meet student needs may be more fraught than before.

A Chegg up on the competition

One example of this challenge is chegging. The term describes the act of using online homework assistance services to cheat. It’s named as the practice has become synonymous with the education technology company Chegg. (Itself a portmanteau of the words chicken and egg. Language is weird like that.)

The driving force behind chegging is the company’s Chegg Study service. For $15 a month, students can upload a homework or test question and receive an answer in about 45 minutes. As noted in a Forbes article detailing the scandal, the question is outsourced to India, where a freelance expert supplies a step-by-step explanation. And while the company offers other services, Chegg Study has been the source of its meteoric growth.

“Subscriptions to Chegg have spiked since nearly every college in the world went virtual,” Susan Adams writes for Forbes. “In the third quarter, they grew 69% over the previous year, to 3.7 million. Nine-month revenue surged 54% to $440 million through September and is projected to hit $630 million for the year.” Although Adams lacked the final 2020 numbers, they have since been released and show Chegg ending 2020 with a record 6.6 million subscribers.

Meanwhile, a study published in the International Journal for Educational Integrity analyzed data of how students used Chegg across five STEM subjects. They found that help requests posted between April and August 2020 increased by 196 percent (compared to the same time in 2019).

“Given the number of exam-style questions, it appears highly likely that students are using this site as an easy way to breach academic integrity by obtaining outside help,” the study’s authors concluded.

University faculty and staff were quick to catch on and began investigating the academic malfeasance. At Texas A&M University, faculty members noticed students answering questions with remarkable speed only to discover entire exams posted on Chegg. Similar stories occurred at Georgia Tech and Boston University, prompting BU faculty to offer an ultimatum: Students who acknowledged their breach would be docked one letter grade; those caught without admission would receive an F.

Of course, Chegg is not blind to the situation either. As Nathan Schultz, president of learning services at Chegg, wrote on Medium: “It’s certainly an important topic for discussion and one we care a great deal about at Chegg. In fact, we are working with several leading institutions to find ways to leverage technology to address this very problem. As most of you know, offline schools have struggled with this same issue for decades and use technology to discourage plagiarism.”Namely, Chegg has assisted institutions in their official investigations, banned bad actors from its platform, and offers a service called Honor Shield, which allows instructors to submit exam questions to be blocked during exams.

Cheating in context

Schultz is right of course: Students have always cheated—whether by a clumsy peek at a neighboring desk or more sophisticated methods such as steaming off a water bottle label, writing answers on the back, and then re-adhering it so they can read the answers through the clear plastic. (Or, you know, something like that.)

Perhaps the only thing more varied than the methods is the reasons why. Students may cheat because they feel intense pressure to earn the high marks necessary to enter elite schools. They may perceive a test as unfair or a subject marginal to their educational goals. They may feel they’re in rigged competition with other students who cheat. They may do it out of a sense of obligation to others—the motivator behind fraternity essay mills. They may lack study time due to socioeconomic factors, such as holding down a full-time job or family commitments. And there are always poor time management skills to consider.

The pandemic then created a learning environment perfect for cheating. Online learning plus Chegg not only made it easier but less risky—in the same way downloading the latest video game is easier than trying to filch a physical copy in the store.

“I’m not surprised that people used Chegg,” a student told Boston University’s The Daily Free Press. “I didn’t use Chegg, but it seems like such an easy way to cheat, whereas in a classroom, you’d have to put in so much more effort to try to cheat.”

But the pandemic also heightened students’ stresses, pressures, and anxieties. These are ”the primary psychological drivers of cheating,” according to Douglas Harrison, vice president and dean of the school of cybersecurity and information technology at the University of Maryland Global Campus.

Discussing the International Journal for Educational Integrity study, Harrison points out that the period it covered aligned not only with Chegg Study’s increased usage but also the mid-year pell-mell to switch from traditional to remote learning. “It was immensely disorienting and destabilizing,” he said, adding, “It’s certainly no excuse for cheating, but it’s important context.”

Further, many students became disconnected from the support that could have mitigated pandemic stresses. On-campus facilities such as gyms, libraries, and technology centers were shuttered. Social learning opportunities like study groups become diminished without face-to-face bonding. And while institutions tried to bring counseling services online, many students may not have had access to the private space necessary for such services to be effective.

As constant as the northern star

With students returning this fall, will colleges and universities revert to business as usual? Hopefully not. Institutions that view the difficulties of online learning as indicative of the method’s failure would be doing a disservice to their students.

While surveys overwhelmingly show that students and faculty want to return to some form of on-campus learning, they also show students perceive an immense benefit to online or blended learning—benefits they don’t want to lose. And research has suggested that online learning can be as effective as in-person classes, while other research suggests that blended learning offers the best academic outcomes. Then there are the students who would be otherwise unable to pursue an education without online support.

As with retail, habits have formed in the student customer. These have created new expectations that institutions of higher learning must meet if they want to create meaningful and less anxiety-inducing experiences.

Yes, cheating surged because it was easier for students to do so. But another reason is that students felt isolated from their institutions, their teachers, and fellow students. That’s not to cast blame—the challenges of 2020 were immense; everyone tried their best—but it does show that students need support structures however they pursue their learning. To their credit, colleges and institutions seem to be working toward that goal.

Moving forward, however, services like Chegg’s will be a part of that support, too. Yes, Chegg Study is easily gamed. Yes, it needs to be retooled to be an instrument of process-based learning rather than back-of-the-book answers. But many other Chegg services show a desire to fulfill the needs universities typically ignore. Chegg Money offers expert financial advice, where far too many universities offer only a FAFSA form. The company’s textbook rental service allows students to save much-needed money on what effectively becomes a high-culture doorstop by semester’s end.

As Dan Rosensweig, CEO of Chegg, told us in his Big Think+ class: “[B]y putting the student first, the choices that we make become limited, the definition of success becomes clearer: How does this help the student and can we benefit by doing that? The order in which you do it, how much you’re willing to invest, and the return on that investment become much clearer by putting the customer first.”

So long as universities and Chegg see each other as the competition, they won’t be able to deliver meaningful customer experiences for students. They’ll only reinvent ways to undermine the other. Both will need to rethink their strategies and find ways to work in tandem, making the student’s wellbeing, education, and success, in Rosensweig’s words, their constant “North Star.” And while the pandemic has revealed a dire need for both to rechart their path in alignment with that star, the post-pandemic era offers an unmatched opportunity to course correct.

Watch the full class on Big Think+

Our Big Think+ class with Dan Rosensweig, “How to Win with Your Customers,” explores how to deliver a customer experience that meets their expectations.

- Find Your Company’s North Star

- Learn the Art of Sales

- Go Direct to Consumer to Sustain High Growth

- Reinvent, then Reinvest (A Case Study in Reviving Your Business)

- Get a Next-Generation View of Your Business with Internship Programs

Learn more about Big Think+ or request a demo for your organization today.