The cabbage roll epiphany: Our best chance at depolarizing the United States

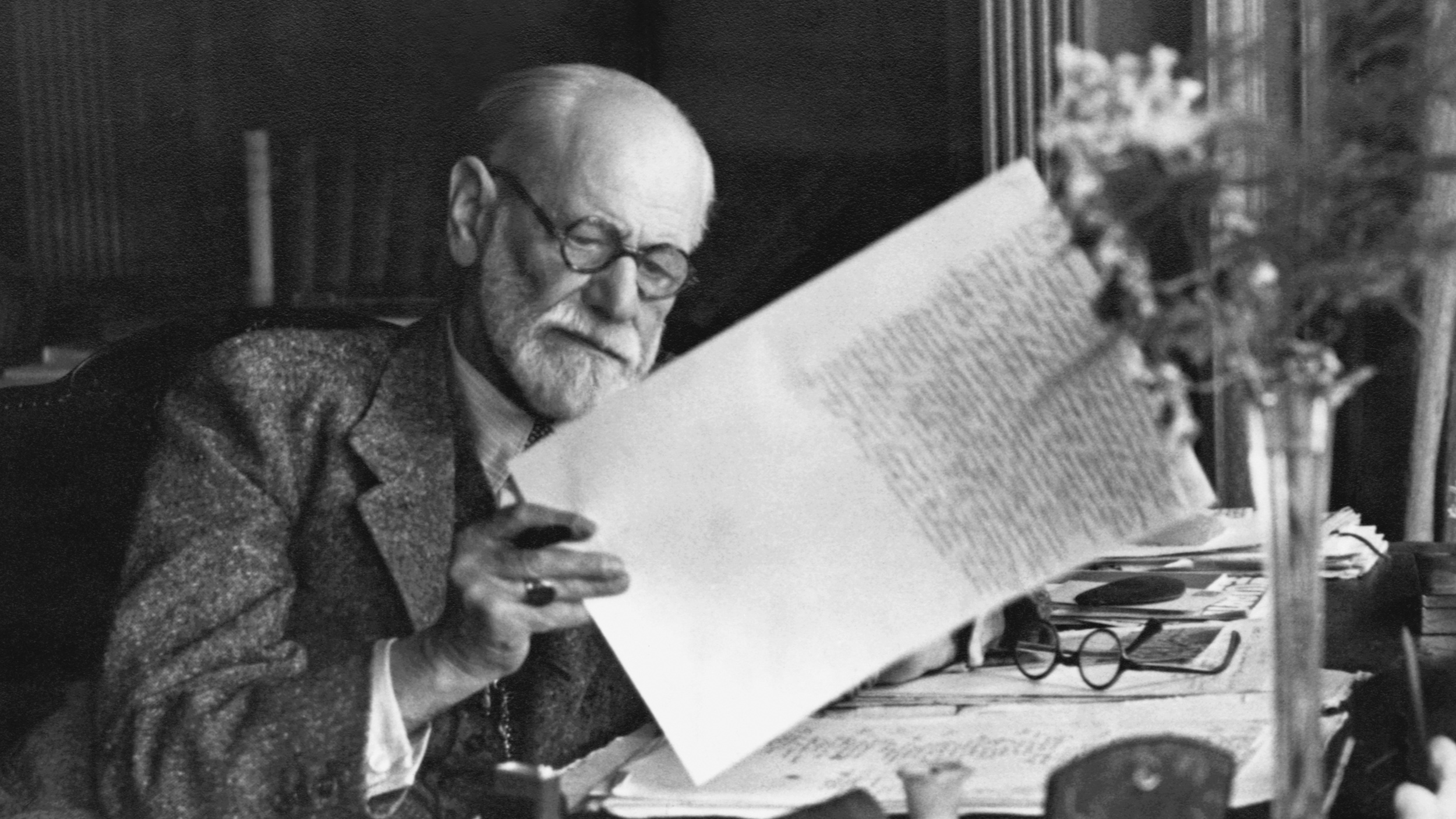

Photo: Jakovo / Getty Images

- Dr. Kurt Gray of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill unpacks a psychological and political phenomenon: reactive devaluation.

- This negative phenomenon is driving polarization in the U.S.. The good news? It has an equally powerful counterpart: benevolence.

- Understanding how humans create meaning in the world is the key to a more unified and a more rational America.

I hate cabbage rolls and for good reason. They don’t taste like much and what they do taste like is bad: boiled cabbage, greasy meat, thin tomato sauce. Cabbage rolls are seldom on the menu at nice restaurants. They do not inspire eyes-closed savoring or 5-star Yelp reviews. Instead, they evoke endless winters, feudal oppression, and culinary fatalism. Despite my loathing of cabbage rolls, I still ate every bite when my grandmother cooked them. It wasn’t just that I feared disappointing her, but instead my grandmother’s cabbage rolls—bad as they were—somehow tasted better than the sum of their parts.

As I would later reveal by rigorous scientific experimentation, the reason my grandmother’s cabbage rolls tasted better was because they were baked with love. “Being baked with love” sounds decidedly unscientific, but studies have revealed how our experience of the world is shaped by social context. Even the most basic of our sensory processes, such as taste and smell, depend on associations and memories. If a passing whiff of shampoo or cologne has ever mentally transported you back to your first love, you know how the world is imbued with meaning.

“The power of perceived malice is not restricted to one side of the aisle but is instead our shared human nature. When Democrats see every one of President Trump’s policies as causing them personal pain, they too are guided by perceived animosity.”

The meaning of an event is so powerful that it can fundamentally change how it impacts us. One study conducted during the Korean war revealed that many American soldiers declined painkillers after sustaining gruesome gunshot wounds. The reason is because the experience of pain depends on the meaning of wounds. Normally being shot is bad news—it means danger and threat—and so we feel pain, but here it meant salvation. As long as they survived the recovery, being shot meant leaving the battlefield and going back home to the safety of America. Later studies in my own lab reveal that our everyday experience of pain is also shaped by meaning: electric shocks actually hurt less when they seem to be given accidentally, and they hurt more when they seem malicious.

The electric shock study has an important lesson for modern America. If perceived malice can make electric shocks—simple physical events—hurt more, then imagine how it can shape our interpretation of comments on Twitter or governmental policies. If you perceive that someone dislikes you (or your group), then everything they do will be experienced as hurtful, even if they are actually trying to help you.

Consider debates about health care. In 2006, Governor Mitt Romney passed a comprehensive state healthcare reform bill in Massachusetts that mandated insurance coverage and expanded Medicaid. In 2010, President Obama passed “ObamaCare,” a comprehensive federal healthcare reform bill that achieved similar goals to “RomneyCare.” Despite the similarities between the bills, and despite supporting Romney in 2012, many Republicans remain outraged. Why? There are differences between the bills, but more likely it is because Republicans experienced ObamaCare through the lens of maliciousness, seeing Obama as trying to undermine their rights.

The power of perceived malice is not restricted to one side of the aisle but is instead our shared human nature. When Democrats see every one of President Trump’s policies as causing them personal pain, they too are guided by perceived animosity. Social psychologists have a term for a similar phenomenon, reactive devaluation, which is when something seems worse just because your opponent offered it to you. In the original 1988 study, Americans were overwhelmingly in favor of bilateral nuclear arms reduction when they believed the suggestion came from President Reagan but strongly against the exact same policy when it was attributed to Mikhail Gorbachev. This phenomena not only reflects zero sum thinking but is rooted in the idea that your opponent is also your enemy—someone bent on hurting you.

“If my grandmother’s love for me can make cabbage rolls more palatable, hopefully understanding that most Americans love their country can make even political disagreement more palatable.”

The drivers of political antipathy are deep problems that are not easily fixed, but the solutions are what many scientists, research centers, and global initiatives are studying. Some early findings reveal that exposure to people on the the other side is important. Once you actually talk with political opponents—or better yet—work together with them, people start to recognize their humanity and become more tolerant of disagreement. It is also important to recognize that we all share deep similarities; for example, we may belong to different political opponents, but we are all Americans (especially on the 4th of July). It also helps to stay away from social media, which not only creates echo-chambers, but also rewards people for being outraged. Combining all these elements together into a “tolerance-cocktail” may help address political intolerance.

Although perceived malice can make the world seem more painful, there is a message of hope: Benevolence can also make things feel better. If you know that someone actually cares for you, then you experience events as more positive. In one study, we gave people a piece of candy (the classic American “Tootsie Roll”) that (we said) was picked out for them by another person. The fictitious person put in a note with the candy that said either, “Whatever. I don’t care. I just picked it randomly,” or “I picked this just for you. Hope it makes you happy.” The addition of thoughtfulness made the candy taste significantly better and also sweeter.

The power of benevolence is also why my grandmother’s cabbage rolls tasted better than I expected. The ingredients may all have been lackluster, but the intention behind them warmed my taste buds. Studies also reveal that the perception of benevolence can also make electric shocks hurt much less. If you know that someone has your best intentions at heart, then an errant electric shock is easily shrugged off. The same is likely true politically: If you know that a congressperson or senator is ultimately trying to help the country, then pain from policies can be better endured.

If my grandmother’s love for me can make cabbage rolls more palatable, hopefully understanding that most Americans love their country can make even political disagreement more palatable.

Dr. Kurt Gray is an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.