New AI-based theory explains your weird dreams

Photo by Bruce Christianson on Unsplash

- A new paper suggests that dreaming helps us generalize our experiences so that we can adapt to new circumstances.

- Therefore, the strangeness of dreams is what makes them useful.

- This idea is supported by some data, though new experiments could help confirm it.

Lots of animals dream, but nobody is quite sure why. Researchers are divided over if dreaming is a mere side effect of other brain functions or if it serves its own purpose.

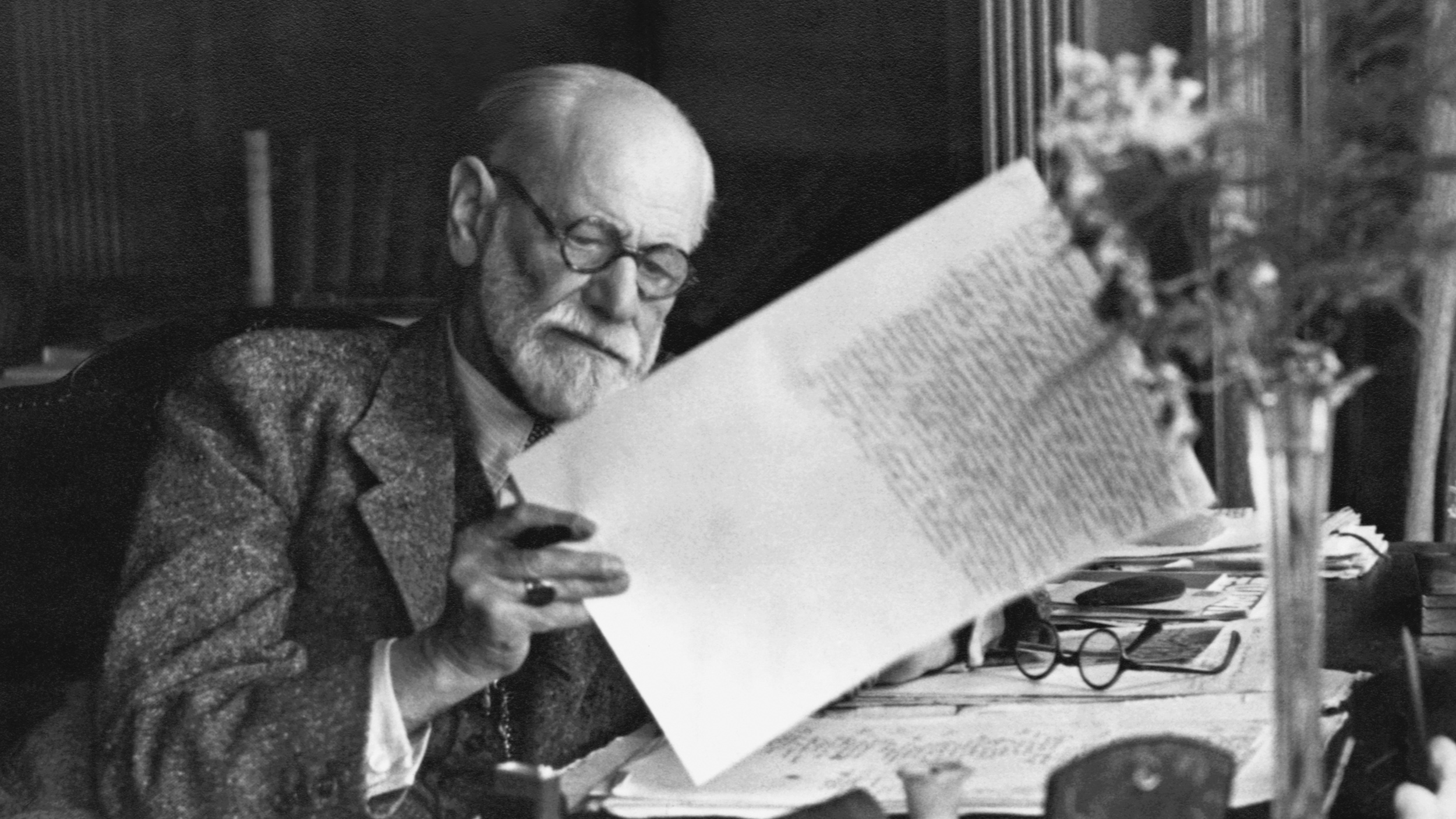

A number of theories attempting to explain dreaming exist. These include the ideas that dreams are needed to regulate our emotional health (the grandchild of Freudian theory) and that they help us psychologically practice for encountering real-world phenomena. The leading contemporary theory is that dreams are involved with or even caused by memory processing and storage.

A newpaper published in the journal Patterns proposes a new hypothesis: dreaming is the brain’s attempt to generalize our experiences, much like how randomness must be used to teach computers how to recognize real world-data. The paper also proposes ways to test it.

Perchance to dream?

The author, Erik Hoel, calls his idea the “overfitted brain hypothesis.” It is based in part on the learning process of artificial neural networks, which are computer algorithms that seek to find patterns in large data sets. These systems are often given training data that is similar, but not identical, to the data that they will analyze later. Practice data is often purposefully contaminated with extra noise and chaos. This is done in order to prevent “overfitting” — in other words, to prevent the neural network from becoming too “narrow minded” and hence unable to identify the bigger picture.

Dr. Hoel’s new hypothesis argues that your brain does something similar through dreaming. The “hallucinogenic, category-breaking, and fabulist quality of dreams” allow our brains to introduce “warped or ‘corrupted'” sensory input for consideration.

In this way, the strangeness of our dreams is a feature rather than a bug.

By presenting us with occasionally bizarre takes on the world, our brains keep us from getting too fixed on the specifics of a task and make us better able to generalize. Dr. Hoel summarizes this rather poetically by saying, “Dreams are there to keep you from becoming too fitted to the model of the world.”

Can Hoel’s dream hypothesis be tested?

Dr. Hoel suggests that evidence for this already exists. It has been shown that repeatedly performing a novel task while awake is a good way to assure that you’ll dream about it that night. He proposes that actions like this trigger the brain’s defense against overfitting, and the weird dreams are the result.

Dr. Hoel’s idea does not necessarily exclude other hypotheses about sleep or dreaming that currently have a fair amount of empirical support. Importantly, he also proposes a few ways to test the predictions made by his hypothesis.

If it is correct, then the effects of sleep deprivation on the ability to memorize would be different from its effects on the ability to generalize. Dr. Hoel suggests that a well designed test examining if sleep or dream deprivation impacts the ability of mice to generalize fears could provide evidence for his hypothesis. Tracking synaptic changes in response to dreams could also be an avenue worth exploring.

Additionally, Dr. Hoel proposes that dream-like stimuli, such as virtual reality or video, could provide similar benefits as dreaming if the over-fitting theory is correct. He explains that this could also serve as the foundation of an experiment to test the hypothesis as well as a possible application of it:

“For example, it may be that a pilot who has been flying for a long period of time is beginning to overfit to their task, and a quick but intense exposure to an entirely different sort of visual stimulus (like a dream-like nature scene in VR) could stave off some of the effects of sleep deprivation. The impact of substitutions can be examined both behaviorally but also at the neurophysiological level of REM rebound.”

If the hypothesis catches on, we may expect to see future studies that seek to confirm or deny the predictions it makes. Until then, we can only speculate on the idea’s possible merits and failings within the framework of what we already know to be true.

Though, I suppose we can also sleep on it.