CRISPR used in human trials for first time in U.S.

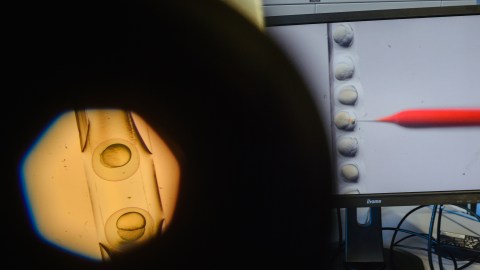

Photo credit: Gregor Fischer / picture alliance via Getty Images

- Doctors used the gene-editing tool in an attempt to treat a 34-year-old patient with sickle cell disease.

- Last year, a Chinese scientist caused major controversy when he used CRISPR to genetically edit two human embryos.

- It’s unclear exactly what risks are involved in gene editing.

For the first time in the U.S., doctors used the gene-editing tool CRISPR to alter the genes of a human.

The patient was Victoria Gray, 34, who suffers from sickle cell disease, a genetic defect in which bone marrow produces a defective protein that renders blood cells unable to carry oxygen effectively.

“It’s horrible,” Gray told NPR. “When you can’t walk or lift up a spoon to feed yourself, it gets real hard.”

In an experimental procedure, doctors took stem cells from Gray’s own bone marrow and used CRISPR to disable the faulty gene — named BCL11A. This disabling boosts the production of fetal hemoglobin, an oxygen transport protein. All humans produce fetal hemoglobin when young, and for decades it’s been thought that this protein, in particular, helps treat sickle cell disease.

Now, researchers are able to put that theory to the test.

“It’s exciting to see that we might be on the cusp of a highly effective therapy for patients with sickle cell,” Dr. David Altshuler, executive vice president, global research and chief scientific officer at Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which is conducting a study with CRISPR Therapeutics, told NPR. “People with sickle cell disease have been waiting a long time for therapies that just let them live a normal life.”

Still, it’s unclear what risks gene editing poses to humans, given that almost all past experiments have been limited to animals and culture dishes. One major risk factor has to do with the interconnectedness of genes and their unmapped functions. For example, in June, a paper published in Nature Medicine described how editing genes to yield one specific benefit might result in a number of unforeseen consequences.

Why CRISPR Gene Editing Gives Its Creator Nightmares

Specifically, the researchers of the new study were examining the potential consequences of a highly controversial gene-editing procedure conducted last year by a Chinese scientist named He Jiankui, who used CRISPR to edit two human embryos, giving them a genetic mutation that theoretically rendered them unable to contract HIV. The scientists’ main takeaway? Their research suggests that people born with that specific mutation tend to die sooner than those who don’t.

“There might be a public perception that one mutation does one thing, but biology doesn’t work like that,” Rasmus Nielsen, an evolutionary biologist who coauthored the paper with one of his postdocs, Xinzhu Wei, told Wired. “I hope this raises awareness that before we think about modifying the human genome with CRISPR, we carefully consider all the possible effects of the mutations that we create.”

Still, for people with life-shortening diseases like sickle cell, the risks of gene editing might be well worth it.

“This gives me hope if it gives me nothing else,” Gray told NPR. It will likely take years of further testing before gene-editing procedures could become available to a wider pool of sickle cell patients.