CRISPR-edited babies born in China may have enhanced brain functions

YouTube

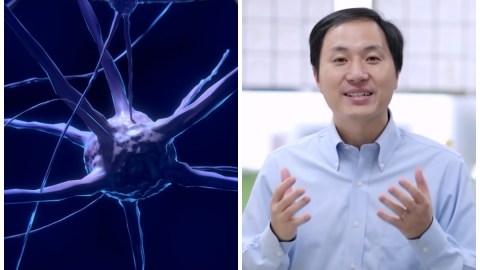

- In November, Chinese scientist He Jiankui reported that he’d used the CRISPR tool to edit the embryos of two girls.

- He deleted a gene called CCR5, which allows humans to contract HIV, the virus which causes AIDS.

- In addition to blocking AIDS, deleting this gene might also have positive effects on memory and cognition. Still, virtually all scientists say we’re not ready to use gene-editing technology on babies.

The controversial decision to genetically edit the embryos of two girls born in China last year might have enhanced their memory and cognition, scientists say.

Chinese scientist He Jiankui reported in November that he’d used the CRISPR editing tool to delete a gene called CCR5, which enables humans to contract HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. In addition to potentially blocking the development of AIDS, recent research suggests knocking out CCR5 can also make mice smarter and help the human brain recover from strokes.

“The answer is likely yes, it did affect their brains,” Alcino J. Silva, a neurobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, whose lab studied the CCR5 gene’s role in memory and cognition, told MIT Technology Review. “The simplest interpretation is that those mutations will probably have an impact on cognitive function in the twins.”

Despite any potential benefits, the scientific community has almost universally condemned the move, which was generally described as a premature use of technology whose physiological and philosophical consequences on human life remain unclear. When Silva learned He had used CRISPR to delete the CCR5 gene, his reaction was “visceral repulsion and sadness.”

“I suddenly realized, ‘Oh, holy shit, they are really serious about this bullshit,'” he told MIT Technology Review.

The CRISPR co-founder’s response to He

Jennifer Doudna, a professor of chemistry and molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley and co-inventor of CRISPR, published a statement in November saying the public should consider the following points on the use of gene-editing technology:

- The clinical report has not been published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature.

- Because the data has not been peer reviewed, the fidelity of the gene editing process cannot be evaluated.

- The work, as described to date, reinforces the urgent need to confine the use of gene editing in human embryos to cases where a clear unmet medical need exists, and where no other medical approach is a viable option, as recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.

In 2017, Doudna spoke to Big Think about the tricky regulatory and philosophical questions we might soon wrestle with if genetically designing babies becomes an option for parents.

As Silva told MIT Technology Review, this kind of selective gene-editing wouldn’t just have consequences for parents and their kids, but also for society at large:

“Could it be conceivable that at one point in the future we could increase the average IQ of the population? I would not be a scientist if I said no. The work in mice demonstrates the answer may be yes. But mice are not people. We simply don’t know what the consequences will be in mucking around. We are not ready for it yet.”