Some scientists speak of a “crisis in cosmology.” They have a good reason

- Just like atoms are the building blocks of chemistry, galaxies are the building blocks of cosmology.

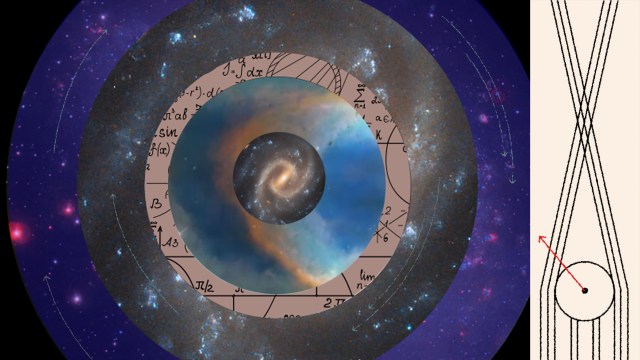

- The standard model of cosmology gives astronomers a way to link observed distances to objects with their age.

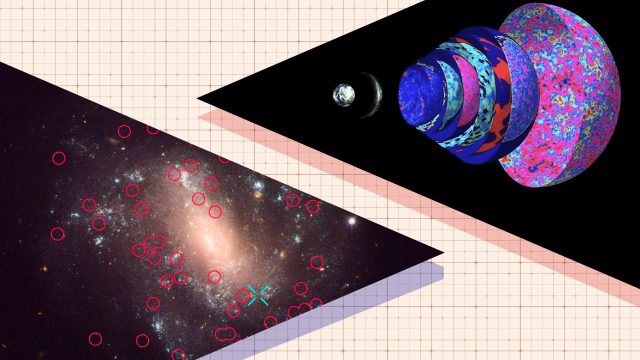

- However, new images from the James Webb Space Telescope found galaxies far more distant (and, hence, far older) than what the standard model of cosmology predicts. The new data provide compelling evidence that the model might need to be updated.

Cosmologists love galaxies more than any other celestial body. Stars and planets are important for problems like the formation of life, sure, but in cosmology, galaxies are the building blocks. Each galaxy is a mostly independent, gravitationally bound collection of billions of stars, and cosmologists can use them to track the evolution of cosmic spacetime itself. The first great cosmological discovery, Hubble’s revelation of the expanding Universe, was accomplished using galaxies. Given this importance, the recent drop of new images from the James Webb Space Telescope has triggered something of a crisis in the field. The images show galaxies forming far earlier than our best models of cosmology predict.

The story the standard model of cosmology tells

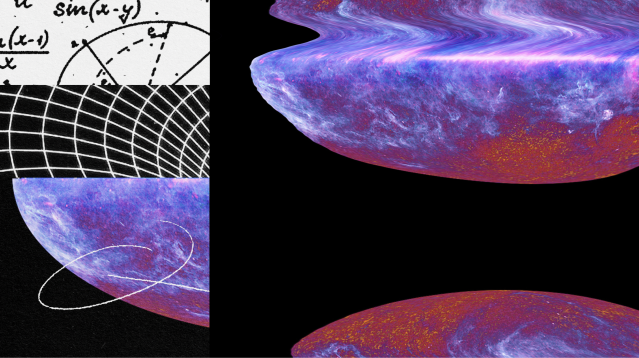

Welcome to another installment of our series exploring emerging and potentially serious challenges to the standard model of cosmology — humanity’s best and most expansive scientific understanding of the Universe. In a recent paper, astrophysicist Fulvio Melia articulated a list of problems that, for him, indicate something fundamental is wrong with the standard model. Melia is not alone in wondering whether the standard model’s time might be up. The phrase “crisis in cosmology” is finding its way into a growing number of blogs and podcasts. But what is behind this crisis, and how seriously should we take it?

Today we will take a look at another entry on Melia’s list, one that has grabbed a good share of headlines: the problem of galaxies and what is called the age-redshift relation.

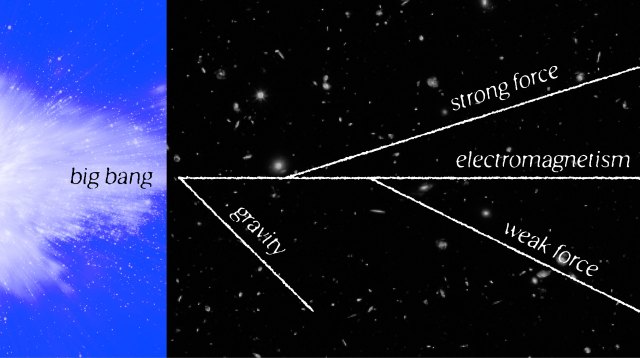

The story of cosmology given to us by the standard model says that about 400,000 years after the Big Bang, electrons and protons found each other to create the first hydrogen atoms. Before this, they had been running free along with the photons that would soon become the cosmic microwave background radiation. Once this recombination into hydrogen occurs, the Universe is largely composed of a fairly smooth gas of these atoms — with some helium around, too — and the left-over background radiation.

Now gravity can get to work within perturbations — small regions of overdensity in the hydrogen gas — and slowly collapse them to form the first stars. It is inside these first stars, which are formed only of hydrogen and helium, that nuclear fusion begins to forge all the heavy elements we know today. Elements like carbon and nitrogen play an important role in the story of galaxy formation. That is because these are the elements that can absorb heat from surrounding gas and emit photons that cool that gas. This cooling process will be critical in helping gas coalesce into galaxies.

Eventually these first-generation stars explode, and the resulting supernovae seed the gas that surrounds them with heavy elements. Each supernova, along with black holes which are also forming, pumps ultraviolet radiation into the Universe. This strips electrons from hydrogen atoms, making the Universe more and more transparent to UV radiation. After the Universe has run through a few generations of stars, there are enough heavy elements and UV radiation around to feed the formation of galaxies. Stars and vast quantities of gas collapse into gravitationally bound entities to pull these first galaxies together.

This is a good story, and observations confirm key parts of it. The problem comes when it is placed within the cosmological context of the expanding Universe.

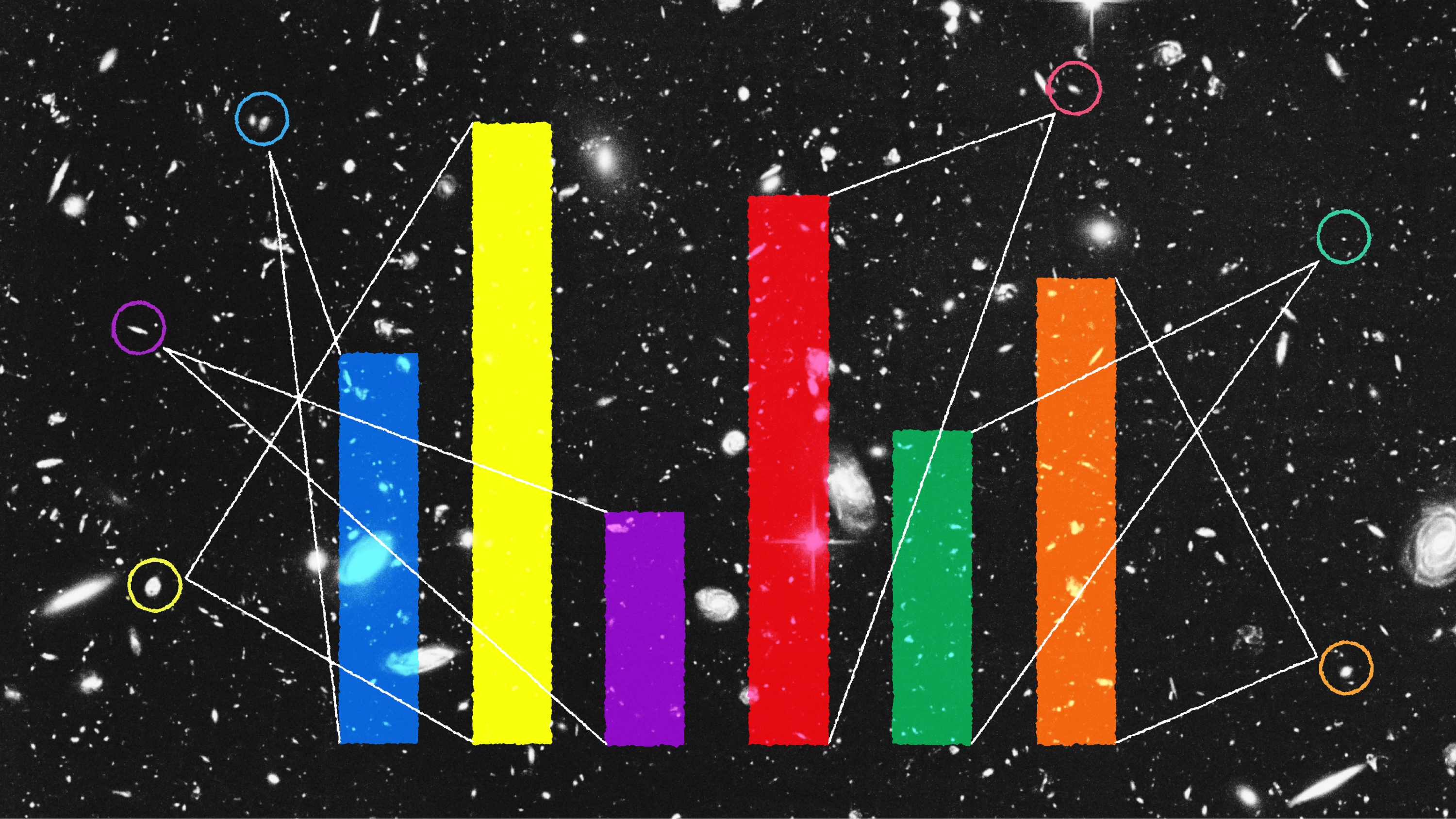

The standard model of cosmology gives astronomers a way to link the observed distances to objects (expressed in redshift) with their age relative to the Big Bang (expressed in years). Distances are measured by observation and cannot be tinkered with. Age, on the other hand, comes from a theoretical story. We take our models of an expanding Universe, guided by Einstein’s general relativity, and pour into them our understanding of matter, as expressed in the standard model of particle physics. Together these tell us how a distance, or a redshift, correlates with an age, a time since the Big Bang.

A crisis in cosmology

So, what is the problem? Almost as soon as JWST was turned on, it found galaxies at redshifts, and hence ages, much farther back than the standard model of cosmology predicts. (The Hubble Space Telescope found hints of this before JWST.)

Here is how the problem plays out. With these images, we are looking very, very far away. Since looking to a particular distance means looking back in time, we are also looking very, very far back in time. But the Universe has a beginning called the Big Bang. The age-redshift relation, which comes from the standard model, tells us how to convert an observed distance into a time after the Big Bang. But there seems to be a mismatch between how old these first galaxies appear to be and how long ago the age-redshift relation tells us they must have formed. Well-formed galaxies are appearing too early for the story we told above to fully play itself out.

The Big Bang model of cosmology shows us a Universe that is evolving rather than static and eternally unchanging. It is not under question in any serious way. (See Marcelo Gleiser’s lovely series on the history of cosmology.) What these new JWST results do throw into question is the story about that evolution that the standard model of cosmology tells us. That is what Melia says needs a big update, and the new data certainly provide a compelling clue that something might be amiss. The real question facing us is how much of an update is needed.