New research reveals what it’s like to inhabit someone else’s body

Photo: UfaBizPhoto / Shutterstock

- The idea of inhabiting someone else’s body can be found in some of humanity’s earliest mythologies.

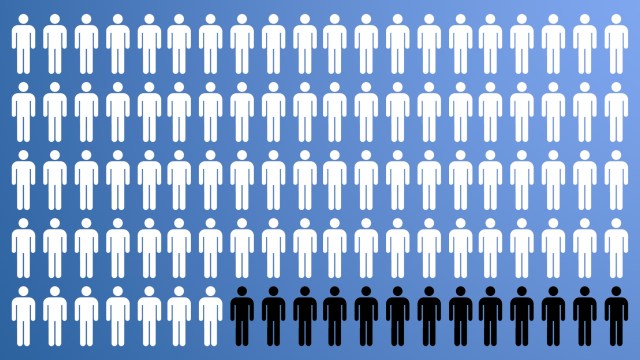

- A team at Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet conducted a body-switching experiment with 33 pairs of friends.

- The findings could have profound clinical implications down the road, such as in depression treatment.

Humans have long been fascinated with the possibility of inhabiting another body, as if consciousness was transferrable through an esoteric (or medical) procedure. Paramahansa Yogananda wrote about his guru dropping his body to take over a dead man by a riverbank (a likely play on a metaphorical transition in the “Bhagavad Gita”). A more humorous example is the 2003 comedy, “Freaky Friday,” in which Jamie Lee Curtis and Lindsay Lohan wake up to find they’ve switched bodies—an existential crisis that ultimately results in a grand moment of empathy.

What if you could accomplish such a feat? Unlike the relatively smooth physical transition in “Freaky Friday,” researchers have suggested that such an act would result in severe disassociation, akin to powerful LSD. Your motor patterns would be different; the way you move through space alone would require an entirely new education. The idea that you’d just pick up where you left off in new skin is implausible.

Humans will try any novel ideas. Though the consciousness-switching tech isn’t quite ready, VR headsets are widely available. While still clunky (due to the weight and feel of the headset), a sense of embodiment is rather convincing. And so a team led by Karolinska Institutet neuroscientist Pawel Tacikowski handed 33 pairs of friends goggles and let them trade places. The results have just been published in iScience.

Sam Harris: The Self is an Illusion | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

The most fascinating aspect of their findings concerns the concept of self. We often think of our self as an island in an ocean of islands, but reality isn’t quite that simple. As neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran has written, the idea that the self is “entirely private is to a significant extent a social construct—a story you make up for others.” This narrative imposes social stability and also acts as cover to shield your true feelings from others.

Decades of neuroscience research has found the self is not a fixed identity but a fluid state of being. “You” change according to the environment you’re in and the people you’re around. Changes are often undetectable, as least to you. You likely don’t realize your “self” depends on everything around you at all times. There is no island.

It’s not that you don’t bring anything to the table, however. Your memories—specifically, episodic memories—play a leading role in perception. Because of this, the very concept of “reality” is often debated. Is shared reality possible? Likely not. You regularly create reality based on your past experiences.

Upon assuming their friend’s body, volunteers in this study assigned their friend’s personality characteristics to their new skin. This process was informed by their own memories of the other person.

“These findings demonstrate that our beliefs about [our] own personality are dynamically shaped by the perception of our body and that coherence between the bodily and conceptual self-representations is important for the normal encoding of episodic memories.”

Incredibly, this meant the volunteer lost track of who they are. Their perception of their friend dominated while inhabiting a foreign body. They ended up performing worse on memory tests about their own lives due to how bound up those memories are with their bodies. A major strike against dualism.

Photo: Crystal Eye Studio / Shutterstock

While this might seem like a freaky and fun experiment, Tacikowski is looking at the real-world applications of such a phenomenon.

“People who suffer from depression often have very rigid and negative beliefs about themselves that can be devastating to their everyday functioning. If you change this illusion slightly, it could potentially make those beliefs less rigid and less negative.”

Tacikowski first wants to further investigate the neural correlates of body-switching. He’s interested in how we construct the self in the first place. Once that’s better understood, he believes clinical applications will naturally follow.

This sort of research also helps overturn an inherent biological impulse to separate body and mind. As neuroscientist Antonio Damasio writes, we need to recognize both aspects of ourselves as continuous partners.

“They are not aloof entities signaling each other like chips in a cell phone. In plain talk, brains and bodies are in the same mind-enabling soup.”

Still, an unshackled imagination leads to great storytelling, like Krishna on a battlefield and Yogananda on a riverbank. There’s no harm in such tales provided we recognize them as metaphors. Until then, we dream forward the possibility until science fiction again becomes real.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter, Facebook and Substack. His next book is “Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.”