How to reclaim deep thinking: Ditch Google, trust yourself

- Online tools give us the illusion of thinking — but they let us surrender control of our synapses to algorithms.

- Thinking is about unlearning the habit of looking to others for answers.

- Deep thinking requires time and concentration; shallow thinking produces shallow ideas.

We don’t think with a pen and paper. We “think” with Google. It feels better to start from a known place and leverage someone else’s ideas than it does to stare at a blank page and form our own. We don’t even have to complete the search query ourselves.

Google’s auto-complete function takes that momentous burden off our shoulders by telling us what we should be searching for and what we should be thinking. We then sift through SEO-optimized results to find the answer to life, the universe, and everything. This process gives us the illusion of thinking — when, in reality, we just surrendered control of our precious synapses to manipulative algorithms.

Glennon Doyle, the best-selling author of Untamed, once found herself in this position. Sitting in bed at 3 am, she typed the following question into the Google search bar: “What should I do if my husband is a cheater but also an amazing dad?” In a moment of clarity that escapes many people, she stared at that question and thought: “I’ve just asked the internet to make the most important and personal decision of my life. Why do I trust everyone else on Earth more than I trust myself? WHERE THE HELL IS MY SELF?”

I’ve been in Doyle’s position more times than I care to remember. In fact, when I was writing the chapter you’re reading right now, I found myself Googling Why is my book so hard to write? — as if a faceless crowd of strangers and bots I’ve never met could find a solution to my writer’s block.

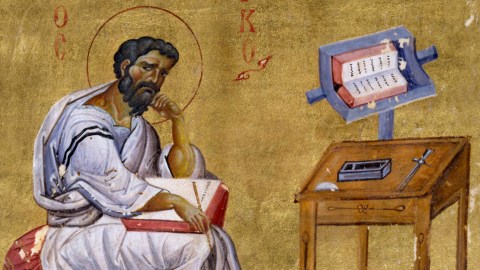

We’ve lost touch with one of the most basic of human experiences — thinking. We beg for answers from others, like Tolstoy’s fabled beggar pleading for pennies from passersby — while unaware that he’s sitting on a pot made of gold. Instead of digging deep into our core to find clarity, we outsource life’s most important questions to others and extinguish the fire of our own thoughts. These suppressed thoughts then come back to haunt us: In works we admire, we see ideas that we crushed because they were our own.

As Bob Dylan reminds us in “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” When we look to the weatherman to figure out answers we can find ourselves, we lose the ability to think for ourselves.

Thinking for yourself isn’t just about reducing external inputs. It’s about making thought a deliberate practice — and thinking about an issue before researching it. It’s about unlearning the habit — programmed into us in school — of immediately looking to others for answers and instead becoming curious about our own thoughts.

As Bob Dylan reminds us: “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

Let’s say you’re curious about where good ideas come from. Instead of jumping on Google right away, or even reading relevant books, think about the question first on your own. Search inside your own mind, mine it for relevant ideas, and jot them down. If you reverse the order — if you think after you read — other people’s opinions will exert too much gravitational pull on your own. Captured by their orbit, you won’t reach escape velocity. Your own ideas will end up deviating only marginally, if at all, from what you’ve read.

When you begin exploring your depths, the initial thoughts you encounter often won’t be your best. These will be the stories you’ve told yourself or the conventional wisdom on the subject. So resist the tendency to settle on the first answer and move on. Deep thinking requires time. It’s only by concentrating on the problem or question long enough that you’ll dive deeper and locate better insights.

Most of us resist setting aside time for deep thinking because it doesn’t produce immediate tangible results. With every email you answer, you make visible progress toward inbox zero. With every minute you think, nothing seems to happen — at least not on the surface. As a result, most people don’t stay with their thoughts long enough before reaching for the nearest available distraction.

“I don’t have time to think” really means “Thinking is not a priority for me.” A commitment to deep thinking is shockingly rare even in professions where the value of original ideas is clear. But shallow thinking produces shallow ideas — along with bad decisions and missed opportunities. Breakthroughs don’t happen in 60-second bursts of thought between meetings and notifications.

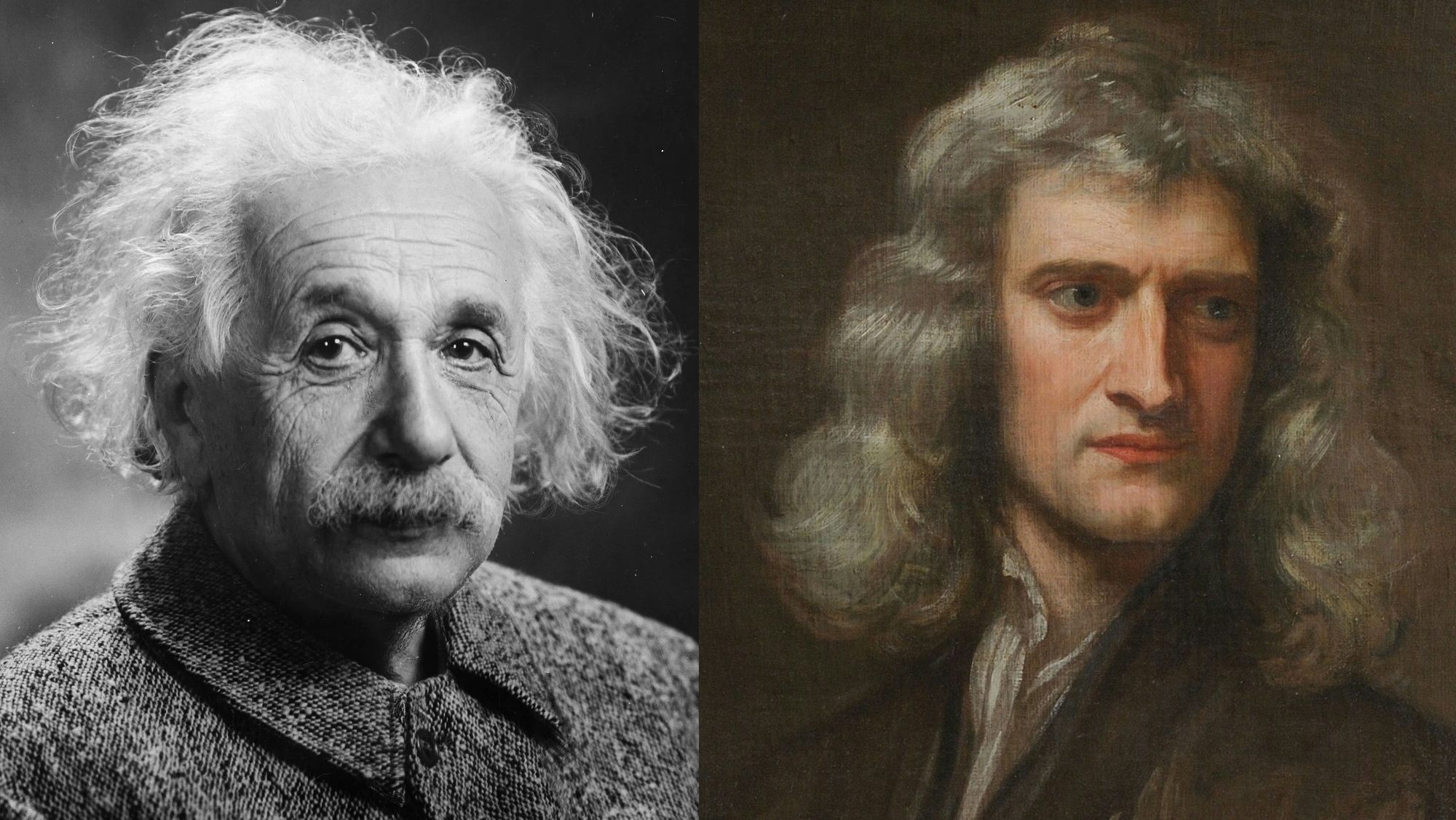

Pop culture exacerbates shallow thinking. When it comes to explaining how breakthroughs happen, storytellers focus on the “eureka” moment when a fully formed insight seemingly appears in an effortless flash. A clip of someone thinking for a long time doesn’t make for exciting television. It’s not thrilling to read: “And then she thought some more.”

But epiphanies are the product of a long, slow burn. Ideas, as the filmmaker David Lynch puts it, are like fish: “If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper.”

Diving deeper requires sustained focus on one idea, one question, or one problem. It’s called “top of mind” for a reason: This question has to be where your mind drifts when it’s allowed to drift. If you clutter your brain-attic with junk, important ideas will get crowded out by the rest and won’t have the room they need to expand.

After you’ve gone deeper on a question by thinking about it yourself, turn to reading what others have written about it. But don’t pause your own thinking. When we read, we often don’t engage with what we read. We see through the author’s eyes, instead of our own. We passively absorb their opinions without thinking for ourselves. As a result, reading becomes a way of shirking responsibility.

Underlining or highlighting passages in what you read isn’t enough. It’s also not enough to ask, What does the author think? You need to also ask, What do I think? Where do I agree with what I’m reading? Where do I disagree? Just because Gordon Wood wrote it doesn’t make it right — and his perspective certainly isn’t the only one. In addition to reading between the lines, also write between them — scribble in the margins and hold imaginary dialogues with the author.

The goal of reading isn’t just to understand. It’s to treat what you read as a tool — a key to unlocking what’s inside of you. Some of the best ideas that come up when I’m reading a book aren’t from the book. An idea I read will often dislodge a related thought in me that was previously concealed. The text will act as a mirror, helping me see myself and my thoughts more clearly.

Your own depths aren’t a place to escape reality. They’re a place to discover it.

Breakthroughs lie — not in absorbing all the wisdom outside of you — but in uncovering the wisdom within you.