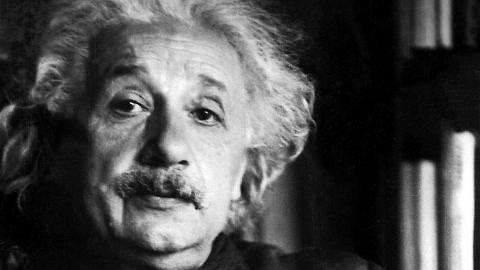

Albert Einstein’s Surprising Thoughts on the Meaning of Life

Albert Einstein was one of the world’s most brilliant thinkers, influencing scientific thought immeasurably. He was also not shy about sharing his wisdom aboutother topics, writing essays, articles, letters, giving interviews and speeches. His everyday-life opinions on social and intellectual issues that do not come from the world of physics give an insight into the spiritual and moral vision of the scientist, offering much to take to heart.

The collection of essays and ideas “The World As I See It” gathers Einstein’s thoughts from before 1935, when he was as the preface says “at the height of his scientific powers but not yet known as the sage of the atomic age”.

In the book, Einstein comes back to the question of the purpose of life, and what a meaningful life is, on several occasions. In one passage, he links it to a sense of religiosity.

“What is the meaning of human life, or, for that matter, of the life of any creature? To know an answer to this question means to be religious. You ask: Does it many any sense, then, to pose this question? I answer: The man who regards his own life and that of his fellow creatures as meaningless is not merely unhappy but hardly fit for life,” wrote Einstein.

Did Einstein himself hold religious beliefs? Raised by secular Jewish parents, he had complex and evolving spiritual thoughts. He generally seemed to be open to the possibility of the scientific impulse and religious thoughts coexisting in people’s lives.

“Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind,” said Einstein in his 1954 essay on science and religion.

Some (including the scientist himself) have called Einstein’s spiritual views pantheism, largely influenced by the philosophy ofBaruch Spinoza. Pantheists see God as existing but abstract, equating all of reality with divinity. They also reject a specific personal God or a god that is somehow endowed with human attributes.

Himself a famous atheist, Richard Dawkins calls Einstein’s pantheism a “sexed-up atheism,” but other scholars point to the fact that Einstein did seem to believe in a supernatural intelligence that’s beyond the physical world. He referred to it in his writings as “a superior spirit,” “a superior mind” and a “spirit vastly superior to men”. Einstein was possibly a deist, although he was quite familiar with various religious teachings, including a strong knowledge of Jewish religious texts.

In another passage from 1934, Einstein talks about the value of a human being, reflecting a Buddhist-like approach:

“The true value of a human being is determined primarily by the measure and the sense in which he has attained liberation from the self”.

This theme of liberating the self to glimpse life’s true meaning is also echoed by Einstein later on, in a 1950 letter to console a grieving father Robert S. Marcus:

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us “Universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish it but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind.”

In case you are wondering whether Einstein saw value in material pursuits, here’s him talking about accumulating wealth in 1934, as part of the “The World As I See It”:

“I am absolutely convinced that no wealth in the world can help humanity forward, even in the hands of the most devoted worker in this cause. The example of great and pure characters is the only thing that can lead us to noble thoughts and deeds. Money only appeals to selfishness and irresistibly invites abuse. Can anyone imagine Moses, Jesus or Gandhi armed with the money-bags of Carnegie?”

In discussing the ultimate question of life’s real meaning, the famous physicist gives us plenty to think about when it comes to the human condition.

Can philosophy lead us to a good life? Here, Columbia Professor Philip Kitcher explains how great minds—like Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Confucius, Mencius, Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre—can help us find meaning and wellbeing in human existence—even if there is no “better place“.

Related reading: Sapiens: Can Humans Overcome Suffering and Find True Happiness?

Related reading: A Growing Number of Scholars Are Questioning the Historical Existence of Jesus Christ