Dark tourism: Inside a new, morbid kind of travel

(Paula Bronstein/ Getty Images)

- A new form of tourism that focuses on visiting sites associated with death and tragedy is growing in popularity.

- Some call it exploitative, and some call it respectful. Still others consider it to be far too dangerous for reasonable people.

- In any case, dark tourism showcases humanity’s irresistible fascination with death.

Maybe you’ve saved your vacation time up for a while and are looking forward to flying off to some idyllic Caribbean island. Maybe Barbados or the Virgin Islands. You’ll get to put your feet up on the beach, suck down a Pina Colada or juice straight from a fresh coconut. You’ll probably go to bars at night that have been heavily influenced by Jimmy Buffet.

There’s certainly one viable option for a vacation destination. But instead, you could fly to Eastern Europe to tour Nazi and Soviet death camps, maybe see a human skull or several thousand, or fly to Afghanistan and carefully plan out exactly which provinces you can visit to minimize the likelihood of triggering a roadside IED.

If the latter put a morbid smile on your face, you might be into dark tourism.

Traveling for fun and terror

Dark tourism is the practice of traveling to places associated with death and tragedy. Of course, Caribbean islands certainly have had their fair share of death and tragedy, but their terrible history isn’t generally the reason why tourists visit those kinds of places.

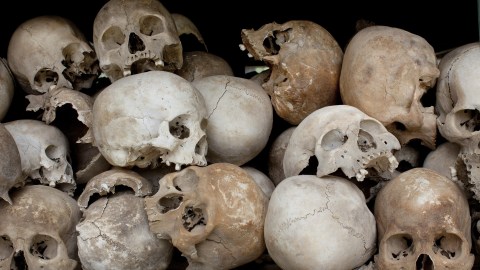

If you were to travel to Choeung Ek in Cambodia, one of the killing fields where the Khmer Rouge executed over one million Cambodians, that would be an example of dark tourism. At this site, you can walk above the more than 17,000 murdered men, women, and children who were dumped into mass graves. Finding loose human bones in the fields at Choeung Ek is a fairly commonplace phenomenon. They also have kindly displayed the skulls of 8,000 human beings in a glass stupa, a kind of Buddhist monument.

Another dark tourism destination would be the Karosta prison in Latvia, a military prison where the Nazis and Soviets housed, tortured, and shot Latvian deserters. Now (after signing a form indicating your consent), you can spend a night inside the prison and receive insults and physical punishment for disobeying the prison guards.

A collapsed building in Fukushima prefecture. After the accident at Fukushima power plant, the area was evacuated. Now, it’s a travel destination for dark tourists, who often come equipped with chirping Geiger counters.

(Athit Perawongmetha/Getty Images)

Why dark tourism?

Writing for The Guardian, Professor John Lennon explains that “Our motivations are murky and difficult to unravel: a mix of reverence, voyeurism and maybe even the thrill of coming into close proximity with death.” Professor Lennon wrote the aptly named book Dark Tourism in an effort to explain what it is about death and tragedy that so many of us find compelling.

“‘Dark tourism’ sites,” he says, “are important testaments to the consistent failure of humanity to temper our worst excesses and, managed well, they can help us to learn from the darkest elements of our past.” But he cautions that “we have to guard against the voyeuristic and exploitative streak that is evident at so many of them.”

Netflix’s Dark Tourism series, for example, has toed the line between respectful and exploitative. In the show, journalist David Farrier visits nuclear ghost towns near Fukushima, cultists in New Orleans who drink human blood, and other grim attractions. The show has been criticized as simply taking unfamiliar cultures and practices and framing them as sinister. Moreover, the very practice of dark tourism itself can be seen as an inherently sordid and cruel transformation of human suffering into amusement for rich Westerners.

Even darker tourism

Although dark tourism is already an extreme travel experience, there are some versions that push the envelope even further. There’s no officiating body that defines what dark tourism is or isn’t, but some dark tourists insist on distinguishing between “real” dark tourism and other types of tourism with increasingly grim adjectives, like war, danger, or natural disaster tourism.

These types of travel are relatively self-explanatory. Believe it or not, some dedicated tourists do travel to Afghanistan, North Korea, Iraq, and other places that are either simmering with violence or in active conflict. Kidnapping is a real risk for these tourists, including Koda, a Japanese tourist who traveled to Iraq in 2004 and was beheaded by militants, and Colin Rutherford, a Canadian tourist kidnapped by the Taliban in 2010 and released in 2016.

The travel group Untamed Borders specializes in these extreme places, and their website offers travel packages to Somalia, Pakistan, and other unlikely destinations. In the FAQ section of their site, they acknowledge the risks of traveling to places like this:

“We take extra precautions in Afghanistan. We often split into smaller groups when walking around cities to keep a low profile. We keep the details of our itinerary to a few selected people. Also, when travelling between cities we take more than one vehicle so that we will not be left stranded in the case of breakdown.”

While whether or not these kinds of experiences fall under dark tourism is up to the growing field of academics studying the phenomenon, it’s clear that they bear some kind of relation. For whatever reason, people are attracted to getting as close to death—whether it’s the deaths of genocide victims or their own—as possible without tipping over the edge.

Dark tourism is becoming more and more popular. Auschwitz, for instance, had its most visitors ever in 2017. As long as human beings remain fascinated by the concept of death, dark tourism will remain a lucrative industry.