Even if you’ve never studied animation, chances are you’re familiar with something called the “uncanny valley.” An important concept in aesthetics and psychology, it refers to the uncomfortable sensation we sometimes experience when we look at computer-generated images of humans and humanoid creatures that seem suspiciously lifelike, but — of course — are not.

The key word here is “suspiciously,” because we do not have the same responses when we look at images that are stylized. As such, the hidden mechanisms that give rise to the uncanny valley effect seem to have less to do with what we find ugly or scary, and more to do with how we have been biologically trained to recognize members of our own species.

Until recently, the uncanny valley seldom came to our attention because artists did not have the mediums necessary to create images that were both animated and lifelike. While Rembrandt’s paintings and Michelangelo’s statues look incredibly realistic, they do not move. Animation does, but most animators opt for cartoonish styles to save on time as well as money.

The uncanny valley did not become widely known until computer animation arrived on the scene. Thanks to this new and exciting medium, creating lifelike images became easier than it had ever been before. While navigating the valley proved trickier than expected, animators continue to discover innovative and clever tactics to circumvent it altogether.

The origins of the uncanny valley

Although the term is now mostly associated with animation, the problems posed by the uncanny valley were initially encountered in robotics, where they were described by Masahiro Mori, a former professor of robotics at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. In a 1970 essay, Mori wondered how people might respond to the humanlike robots he was making.

Biology suggested this response would be positive, as studies show that our capacity for empathy is strongest toward members of our own species, and decreases the farther a particular organism is removed from our position on the evolutionary tree. But as Mori accurately predicted, this was not the case with lifelike robots.

In the words of the publication that authorized the one and only official translation of Mori’s essay into English, the robotics professor “hypothesized that a person’s response to a humanlike robot would abruptly shift from empathy to revulsion as it approached, but failed to attain, a lifelike appearance.”

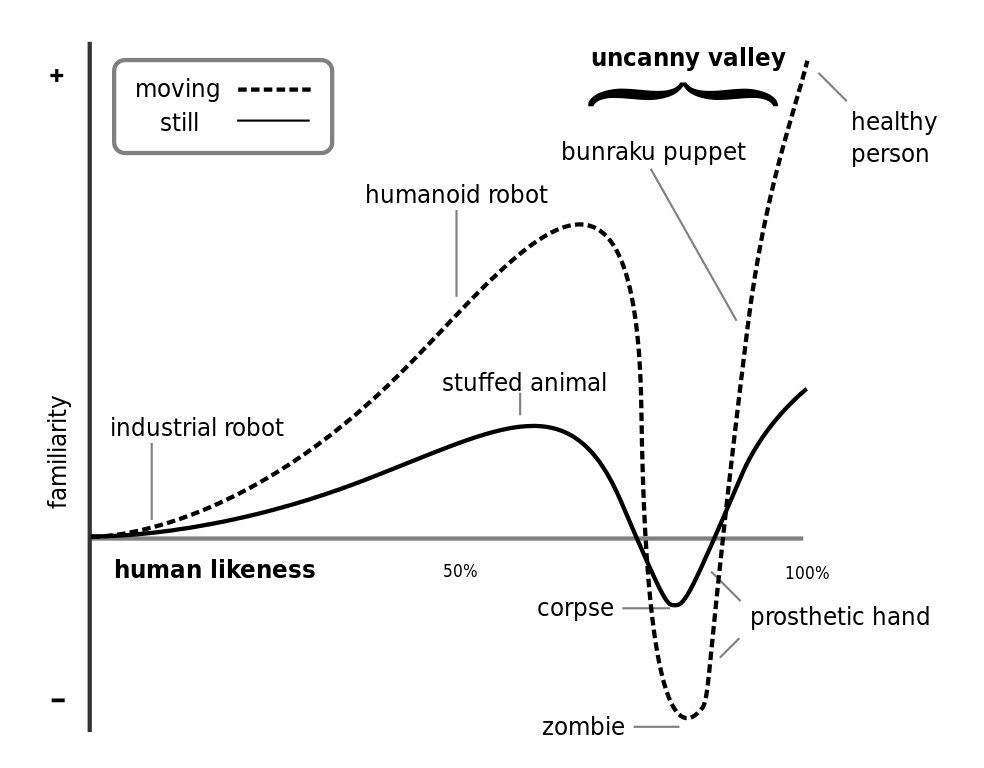

Mori also drew up the now-famous diagram comparing the eeriness associated with various humanoid entities. Non-humanoid industrial robots provoke neither sympathy nor disgust, while vaguely humanoid stuffed animals strike us as cute. The uncanny valley, meanwhile, is populated by things that seem human but aren’t, including lifelike dolls and corpses.

Lessons from video game design

The power of the uncanny valley effect has proven too powerful to ignore. It has forced robotics engineers to reconsider how they might implement artificial intelligence in society, and has been listed as a primary cause for the critical or commercial failures of important films, from last year’s Cats to the digital de-aging seen in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman.

But while films continue to struggle with creating digital renditions of actors, video game developers seem to be doing just fine. In Japanese designer Hideo Kojima’s latest game, Death Stranding, players encounter fully digitized versions of actors Norman Reedus and Léa Seydoux that are not at all uncanny.

Kojima isn’t the only designer to have circumvented the valley. The main antagonist of the surival game Far Cry 6, released last month, is portrayed by none other than the Breaking Bad actor Giancarlo Esposito. Esposito’s movement and likeness were recorded using motion-capture technology, and his in-game appearance is similarly convincing.

How can the digital renditions of Reedus and Esposito look believable, while a de-aged version of Robert de Niro cannot? One explanation is that in video games these renditions blend in with their equally digitized surroundings, while in films the same sort of CGI stands out like a sore thumb when placed next to real-life actors and environments.

Bridging the uncanny valley

Robotics engineers have long understood that the power of the uncanny valley depends on context and categorizations. If a robot resembles a machine more than a human being, people will hold it to the same standards as they do a machine. Conversely, if the robot resembles a person, it will be judged by how well it can mimic one.

Understanding how the uncanny valley works is often the first step in circumnavigating it. Interactions, a bi-monthly magazine on design and engineering, outlines a number of methods animators can use. They advise to “steer clear of atypicalities at high levels of realism,” and point to the large, anime-style eyes plastered on the heroine of Alita: Battle Angel as an example.

Getting the eyes right is especially important, as these are the facial features people often pay the closest attention to when they interact with others. If you’re looking to create a realistic character on a limited budget, therefore, you may want to focus most of your efforts on these organs, though the authors also stress that levels of detail should be consistent throughout the entire model.

At the end of the day, however, some of the greatest achievements in computer animation are the ones that manage to use the effects of the uncanny valley to their advantage. Think, in this case, of Gollum from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings — a character whose creepiness the uncanny valley actually helped accentuate.