New study determines how many mothers have lost a child by country

USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

- A first-of-its-kind study examines the number of mothers who have lost a child around the world.

- The number is related to infant mortality rates in a country but is not identical to it.

- The lack of information on the topic leaves a lot of room for future research.

Among the best indicators of societal progress over the last few decades has been the remarkable decline in infant and child mortality rates worldwide. In the early sixties, a staggering 1 in 4 children around the world died. Today, that rate has fallen to fewer than 1 in 10. The continued efforts of several organizations will help that number to fall even further.

However, like many other kinds of progress, the blessings of these advances have been shared unequally. Child mortality rates are much higher in some parts of the world than in others. Additionally, measuring infant mortality by itself doesn’t tell the whole story. While conditions are improving, the legacy of high child mortality rates endures.

In hopes of shedding light on both issues, a first-of-its-kind study suggests that mothers in some parts of the world remain astronomically more likely to lose a child than others.

Bereavement around the world

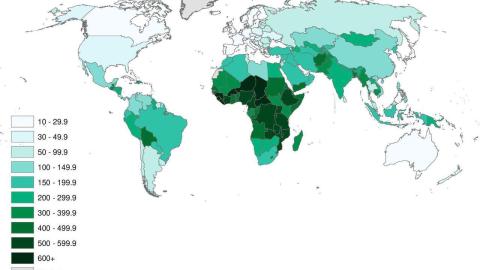

An international team of researchers led by Dr. Emily Smith-Greenaway examined data from 170 countries. By combining information on child mortality, maternal life expectancy, the fertility rate, and the proportion of women in the country who have children, among other statistics, the researchers were able to create indices of the number of mothers per thousand who lost a child either before the age of one or five, or ever, for nearly every country in the world.

The results are quite shocking.

As seen in the above map, the countries with the highest maternal bereavement rates are clustered in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Hong Kong has the lowest maternal bereavement rate of any measured locale in the world at 2.8 per 1000, while Sierra Leone has the highest at 303.3 per 1000, nearly 1 in 3. A mother in Sierra Leone is 108 times more likely to have lost a child than a mother in Hong Kong.

This difference is far larger than that of infant mortality alone. There are many possible reasons for this, including factors which directly impact child mortality. Because of the number of factors involved, there are countries where the infant mortality rate remains stubbornly high but where maternal bereavement is rather low, such as the Philippines, and countries where a low mortality rate hides a high bereavement rate, such as Peru.

The differences between countries continue to exist when age is accounted for. While rates are worse everywhere when looking only at older mothers, the difference between Hong Kong, which remains the best, and Liberia, which becomes the worst, is still a factor of 70.

The mental and physical toll of losing a child

The authors of the study suggest that these numbers demonstrate the existence of a previously hidden element of global health and the inequality between nations. Their work shows that the maternal cumulative prevalence of infant mortality is not identical to the infant mortality rate, though it is related. They also warn that their estimates are probably conservative due to the likelihood of unreported infant deaths.

The toll of losing a child on a mother’s mental and physical health is considerable. However, much of the research on this topic ignores the possible effects on other family members. The authors note that what information does exist suggests it can be equally as damaging to them. Additionally, they state that their research focused on national rates but that similar issues may exist within nations where demographic differences in infant mortality and parental bereavement rates exist. They encourage further study into this matter.

Dr. Smith-Greenaway explained the authors’ hopes for the study and the new area of research it identifies:

“We hope that this work will emphasize that further efforts to lower child deaths will not only improve the quality and length of life for children across the globe, but will also fundamentally improve the lives of parents.”