How meth and fentanyl homogenized the illegal drug supply

- Drugs of abuse can stifle our most basic instincts for survival.

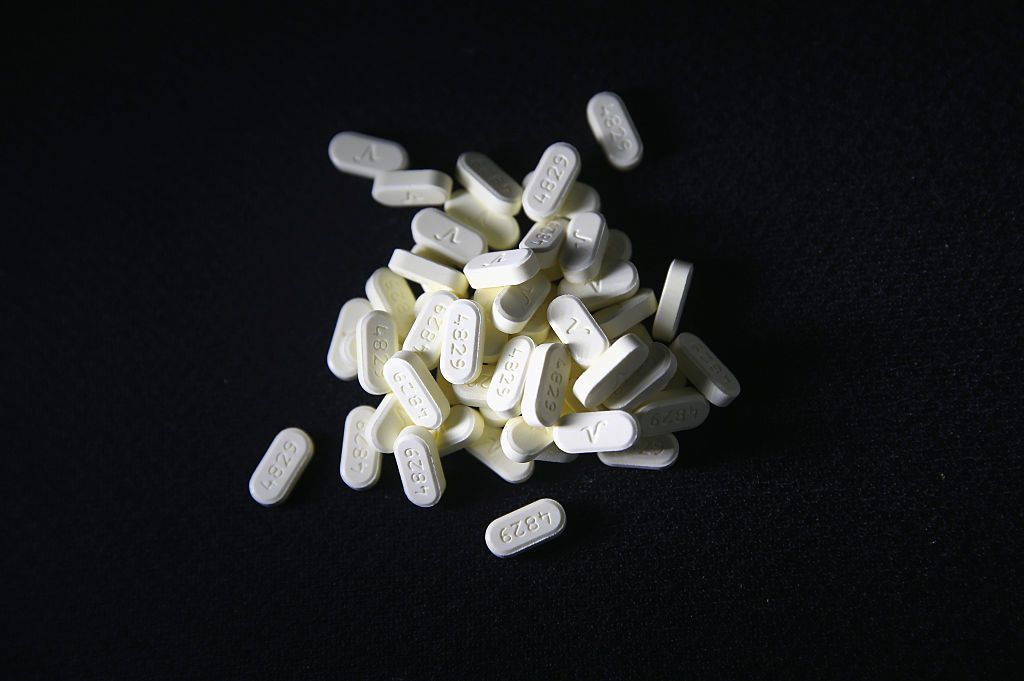

- This has become especially true with the rise of powerful synthetic drugs like fentanyl.

- Drug traffickers have homogenized the drug supply the way corporate America has done fast food, coffee shops, and hotels.

In early 2022, I spent some time in the town of Jeffersonville, Indiana, across the Ohio River from Louisville.

I spoke to Dr. Eric Yazel. Yazel is an emergency room doctor and the health officer for his county. Clark County fentanyl-overdose deaths have soared, he told me. His hospital is Indiana’s first to install a machine dispensing free Narcan, the opioid-overdose antidote.

Meanwhile, tent encampments have spread in Jeffersonville in the last three years, he said, due to cheap and prevalent methamphetamine. Addicts refuse to leave the encampments and their drugs even when offered treatment or shelter during winter, he said. So, even though the winter of 2020–21 was fairly mild, he said, “I saw probably tenfold more frostbite cases than I’ve had any other year.” A week before my visit, a woman froze to death in her tent, despite her mother’s pleas to come back to her five-year-old son, and a warm home and bed.

Listening to Eric Yazel, I was struck again by how powerfully drugs of abuse can stifle our most basic instincts for survival. All drugs of abuse, from alcohol to heroin, do this to some degree. What’s different now is the intensity with which synthetics, in massive supply and potency nationwide, impose that obedience on our brains, even as they assure death or madness. As I write, Covid now seems in retreat. Our attention is now freed to focus elsewhere. With that, more Americans are noticing the disturbing display across our country of how these drugs hijack users’ brains and divert those immense instincts toward finding and using dope no matter the risk.

In fall 2021, overdose deaths were reported to have surpassed 100,000 for a twelve-month period. A few months later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a record 107,000 overdose deaths for calendar year 2021—one death every five minutes. Close to 70 percent of those deaths involved fentanyl. The DEA sent out an alert of mass fentanyl overdoses in seven towns. Congress designated May 10 as National Fentanyl Awareness Day. Meanwhile, I heard often from folks who had, from their own angles, watched the effects of synthetic drugs on our country.

“We’ve never had a homeless population. We do now,” said J. T. Panezott, chief of police for the town of Salem (pop. 12,000) in northeast Ohio. Meth arrived some two years before and has driven people mad and homeless, he said. People wander the town, he said, imagining they have died and come back as someone new. Panezott said he opened his department lobby to one such man to come in out of the winter cold. “People are going to rehab and coming out and they still can’t fix that psychosis,” the chief said. “It’s still there. I’ve never seen anything like this.” This appears to be a controversial idea—that the meth now coming out of Mexico could be accompanied by mental illness sufficient to push people into homelessness, or to keep them there regardless of the original reason they’re on the street. I don’t know why this is controversial. To anyone who has spent time in tent encampments, it should not be.

West Virginia used to not have a homeless problem to speak of. And, to be sure, West Virginia housing prices are low by any measure. But then P2P meth arrived in 2017 and supplies exploded in 2018 and that changed a lot. As the meth flooded in, tent encampments and stripped and abandoned houses proliferated. The drug made people psychotic, impossible to live with. Morgantown, Parkersburg, Salem, Wheeling, Huntington, Charleston—all were West Virginia towns with new eruptions and expansions of tent encampments of homeless people once this meth arrived in such remarkable quantities.

People end up homeless for many reasons and high housing costs can certainly be part of the mix. But the meth that Mexican traffickers began making in 2009, and that I reported on in The Least of Us, did the job quicker and more ferociously, often with apparent damage to the brain. My reporting showed that, in particular, tent encampments are often barometers of this —places where people can use meth and be around others who do the same, using tents as protection from a world of meth-imagined threats. They are where drugs’ stifling and redirecting of our brains’ instinct for survival is most graphic. And they are found not just in Los Angeles and Portland, with their stratospheric housing costs; they are also in rural America, Rust Belt towns, southern Indiana, towns in West Virginia.

Boston had high housing costs for years but no full-time tent encampments until Mexican meth arrived in 2019, and meth prices dropped from $25,000 a pound to $5,500. Then “Mass and Cass”— Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard—became a day-and-night encampment. “Now, it’s people in fits on the sidewalk, no idea where they are, people with no clothes on, walking into the street, screaming at nothing. That didn’t happen until meth was the thing there.”

Michael Barillot told me that he spent the last fifteen years in various forms of homelessness in the Boston area, due to a two-decade opioid addiction that began with a wisdom tooth extraction.

Before meth arrived, he said, most of the homeless people were in shelters at night, and outside during the day. “But you can’t be inside a homeless shelter and be comfortable given the places that meth will take you to, mentally. So now it’s just tents,” he wrote me about a month after the book came out. “People in the same spot all day, hundreds of tents.” Even through Boston’s winter.

Yet though P2P meth was prevalent nationwide, fentanyl continued to dominate the conversation wherever I went. It was in everything now. It seemed to be in most of the country’s cocaine supply. The cases kept mounting. Michael K. Williams, the great actor who brought Omar to life in HBO’s The Wire, had struggled with a cocaine addiction, but he died in 2021 when the cocaine he used contained a fentanyl analogue.

The larger truth on the streets is that no one uses just one drug anymore. Medical examiners routinely find three, four, five drugs in the systems of those who die from overdose. That’s drug use in the time of fentanyl and meth, which are the two most common because they’re made and smuggled in such enormous supplies.

Used to be that drug use differed from region to region across America. Drug traffickers have homogenized the drug supply the way corporate America has done with the commercial offerings—the same fast food, coffee shops, hotels—at every off-ramp on every interstate in the country. What’s more, drug historians have noted long cycles of drug use – from stimulants to depressants and back again, every ten to fifteen years. Meth and fentanyl have flattened and merged those cycles into one; now it’s a stimulant and a depressant, together in unrelenting supplies, nationwide. Because this makes sense to traffickers.