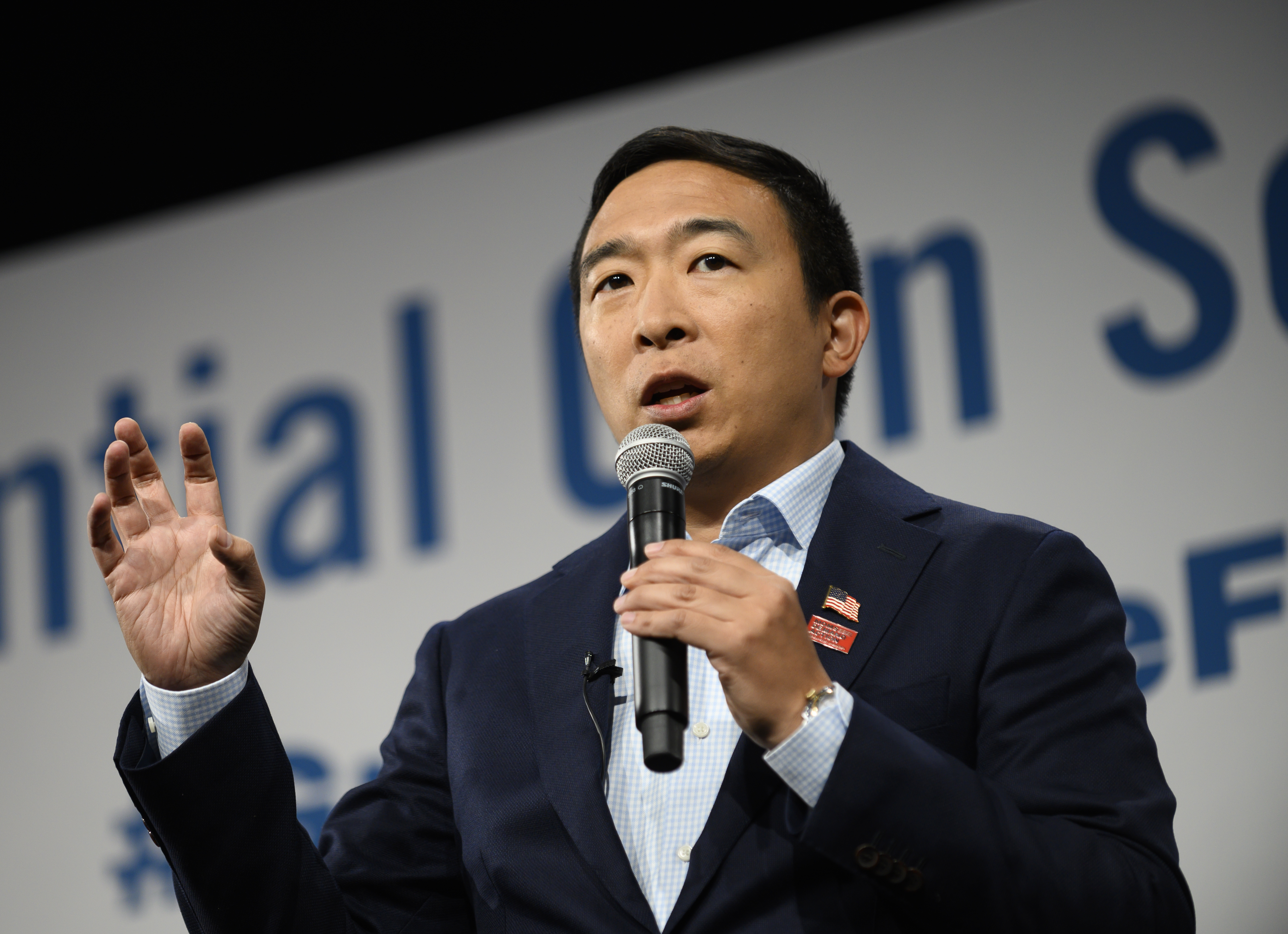

Andrew Yang on how the media shapes our impressions of political candidates

- "Forward: Notes on the Future of Our Democracy" details the surreal experience of running for president, the shortcomings of institutions, and how media shape our perception of political candidates.

- Yang uses his firsthand experience to describe the ways in which news media shape public opinion on political candidates.

- Some reporters in the national news media, according to Yang, feel a responsibility to reinforce particular candidates and their narratives.

From the book FORWARD: Notes on the Future of Our Democracy by Andrew Yang. Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Yang. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Wing Ding is Stacked Against Me; Or, How We Learn About Candidates

“Okay, so now I’m running for president,” I thought in early 2018. I was still quite anonymous, so this decision led to any number of awkward conversations. For example, I would be at a kid’s birthday party and another dad, clutching a beer and making small talk, might ask me, “What do you do for work?” If I answered, “I’m running for president,” it would seem positively bizarre. In theory I should have been working it every waking moment, but the last thing I wanted to do was try to persuade every dad at the birthday party to support me. So I’d answer with something vague like “I’m an author” or “I work in policy” and then change the subject.

My hesitancy seemed justified by what happened when I did actually try to inform people. Every conversation took half an hour. And most people weren’t exactly pumped up afterward. It was more often a confused “Good luck,” like the Citibank teller.

The operator in me continued to tell my brain that the inputs my campaign needed were pretty straightforward. I needed to raise enough money to not just keep the organization running but to grow it. I needed to generate publicity and get press. And I needed to get voters on board, particularly in the first states that would vote. Later, I would come to realize that the process through which one gets press and mainstream coverage is much more institutionalized than I would have ever believed.

I had studied the trajectory of other primary campaigns, and it was clear that Iowa and New Hampshire were the key. If you didn’t perform in those states, you were done; most candidates would drop out even before the early states voted. But if you did well in those first states, it could catapult you forward into contention. Doing well in the early states struck me as fairly achievable. I had gone to high school in New Hampshire and felt confident that my message would hit home there; there’s a healthy independent streak in the Granite State. And in Iowa only 171,517 Iowans participated in the 2016 Democratic caucuses. This was only 5.4 percent of the 3.1 million people in the state. You could assume that the number would grow somewhat in 2020, but the field would also be much more crowded. So my projection was that if I got approximately 40,000 Iowans on board I could win. (Indeed, Bernie Sanders wound up getting the most votes, with 45,652, so my working assumption was pretty close.)

Our system of electing a president operates such that each Iowan was worth his or her weight in gold. I started saying that every Iowan was worth a thousand New Yorkers or Californians, which was essentially true. Getting forty thousand Iowans on board to abolish poverty seemed very doable.

The first bridge to cross was trying to generate attention. And for that we needed the media. The initial New York Times piece had not generated as much follow-up as I’d hoped, but I figured other journalists would take an interest eventually.

That turned out to be much easier said than done.

In the summer of 2018, I was invited to speak at a major Democratic grassroots fundraising event—the Wing Ding—in Clear Lake, Iowa. It was a huge coup for my fledgling campaign at that point. I later found out that I was invited because one of the organizers had heard me on the Sam Harris podcast—one of my first big breaks in terms of exposure earlier that year (more on this later)—and decided that I was worth hearing from.

For me, the Wing Ding was the first time I was getting the chance to address such a large group of people—a thousand—and in front of dozens of reporters. The venue, the Surf Ballroom, is most famous as the place where Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper played right before their plane crashed six miles away in 1959, which was later christened “the day the music died” by Don McLean in “American Pie.” I tried not to dwell on that ominous history, though I absolutely love that song.

It was my first major political speech. It’s not my custom to make emotional appeals, but I also knew, from the numbers, that a knockout performance would get me 2.5 percent of the way to forty thousand if I somehow converted everyone in the room. I approached it as a potentially make-or-break moment for the campaign—the speech of my life up to that point. My team approached it the same way; they had me practice until I could speak without notes, hit my major points, and not go beyond my allocated time

The four major speakers were me, Tim Ryan, John Delaney, and the headliner—Michael Avenatti. John and I were the only declared candidates for president as of the summer of 2018. Most candidates were waiting until after the midterms to declare. It was clear that Michael Avenatti was the draw. The press was salivating over the pugnacious lawyer, who had rocketed to fame as the attorney representing the porn star Stormy Daniels in her lawsuit against Donald Trump, as a possible opponent for the Republican president. For his part, John Delaney had already spent several million dollars, including on Super Bowl ads in Iowa, and had opened ten offices in the state. I, of course, had zero staff and offices in Iowa at the time.

Approaching the ballroom, I saw it was surrounded by “John Delaney for President” signs that had been planted earlier that day. John’s giant blue tour bus and sign spinners—two guys who were very talented at spinning giant “John Delaney” cardboard signs— were very conspicuous in the parking lot. The Wing Ding was my first brush with presidential campaign pageantry as a candidate. It immediately made me feel small and self-conscious showing up with my three young staffers and a meager table with our one brochure.

Still, I was careful not to project any vulnerability. You have to be rock solid because your team will take its cues from you.

I went into the darkened ballroom and began shaking hands with whoever was nearby. Most people didn’t really know who I was, so it was a struggle to seem busy and not look awkward. One of my quick-thinking staffers started to bring people, including local officials, over to meet me.

The program was at least two hours long, with a procession of local candidates and luminaries who gave brief speeches in support of their races. I met local candidates like J. D. Scholten and Rob Sand. Eventually it got to Tim, John, me, and Michael Avenatti. Tim gave a rousing speech about America’s never being knocked down. John spoke earnestly about consensus and bipartisanship.

It was my first time seeing their speeches, but not the last. Eventually, if you’re a candidate, you see each other’s stump speeches over and over again. Late in the cycle, I’d come to joke that Democratic fundraisers should have us draw names from a hat and deliver another candidate’s speech. Donors would pay big money to see it. By the end, I thought I could do a decent rendition of Pete Buttigieg or Bernie Sanders giving their go-to stumps. I can imagine someone parodying my stump: “The robots are coming, we’re doomed, give everyone money right now.”

In the Surf Ballroom, I heard my name called and jogged up to the stage. I talked about how our economy was transforming before our eyes, and why Iowans needed to lead the country in a new and better direction. It felt great. I got a standing ovation from much of the crowd, though the level of applause was likely inflated by Iowa courtesy. (If you want to see the speech, you can judge for yourself by searching online for “Andrew Yang Wing Ding 2018.”)

As I stepped off the stage, there was a small line of people who wanted to shake my hand. I wound up in conversation with John Delaney and his wife, April, who came over to compare notes. While we spoke, Michael Avenatti took to the stage to deliver the last speech of the night. Curious to see how it would go, I turned to pay attention.

Objectively, I thought Michael’s speech was awful. He read from notes the whole time—word for word. He went on for way too long—a full five minutes over the allotted time. Though his speech was filled with cliché-ridden talking points, the Iowans in attendance politely applauded on cue.

Watching all this, I thought, “Okay, anyone seeing this will take from it that Michael Avenatti is not serious.”

I could not have been more wrong.

As soon as Michael finished speaking, he was encircled by a dozen television cameras and journalists peppering him with questions about his presidential run. I didn’t even know half of these journalists were in the room until they swarmed Michael. They followed him in a scrum as he slowly gravitated toward an exit.

The next couple days the headlines ran “Avenatti’s ‘Swagger’ Stirs Iowa Democrats” and “Avenatti at Iowa Wing Ding: Democrats Need to ‘Fight Fire with Fire,’” with glowing quotes from Iowans in attendance about how Avenatti had fired up the crowd and was an appealing counterpoint to Trump.

These stories barely mentioned me or Tim or John. To the national press it had solely been the Michael Avenatti show.

I realized that these journalists had come to Clear Lake, Iowa, for a story that had already been written in their minds. Avenatti, media darling, was exciting voters. His actual performance was incidental, and the speeches of any other candidates who happened to be there—including my big debut—might as well not have happened.

The Media Has its Own Stories in Mind

There’s a common assumption that people run for president because they have big egos and it serves their sense of self. As candidates, they are afforded numerous opportunities to get their messages across because people want to hear what they have to say. Later, they are rewarded with lucrative TV contracts, speaking gigs, and a larger following.

This is seriously off base. Generally the opposite is true. Running for president is, by and large, an ego-destroying, humbling process. And the media is a very big part of that.

Imagine you are the author of thirteen books, including four New York Times number one bestsellers, and a spiritual leader with a following of millions. You count some of the most famous people in the world as your friends and confidants. You have founded a nonprofit that delivers food to people struggling with AIDS and co-founded a nonprofit for world peace. You have improved the well-being and spiritual life of droves of people and are adored and respected by them. You are wealthy, serious, and philosophical.

Then you decide to run for president.

Reporters respond with ridicule, scorn, and eye rolling. Journalists interview you with a patronizing air of skepticism when they decide to interact with you at all. Your past statements are taken out of context and used to ascribe to you beliefs that you do not hold. Eventually, you are denigrated as a wacko and a crystal lady. Everyday Americans contribute millions to your campaign, but that doesn’t seem to matter. You move to Iowa in order to connect with people and campaign your heart out for months on end, and your efforts are essentially ignored.

As you probably guessed, I’m describing Marianne Williamson, whom I found to be warm, generous, thoughtful, and driven by a genuine desire to improve the world.

Or imagine yourself as a former three-star admiral in the U.S. Navy who served for more than three decades and commanded the USS George Washington aircraft carrier strike group in the Persian Gulf in 2002. You have led thousands of sailors who put their trust in you for their very lives. You have a PhD from Harvard and were second in your class at the U.S. Naval Academy. You were a two-term congressman from a swing state and led a nonprofit that promoted STEM education around the world. You see the direction that the country is going and its increased polarization, and you feel that a different type of leadership is needed.

So you decide to run for president.

You are ignored by most of the press. When they do talk to you, journalists regularly ask you, “Why are you running for president?” even though you spent decades in service and the answer ought to be pretty obvious. To the media, you are nearly a nonentity: major networks tell you they will not have you on air even to talk about foreign policy, which you are clearly better qualified to discuss than just about anyone, because they don’t consider you a legitimate candidate. You walk across the state of New Hampshire as a way to generate attention and meet with people, and that is generally ignored too.

That’s Joe Sestak, who struck me as a patriot and great man when I spent time with him on the trail. His daughter, Alex, suffered from cancer, which is one reason he got into the race late. She passed away in 2020.

I could go on and do the same exercise with perhaps a dozen other candidates. Running for president doesn’t serve your ego generally—quite the opposite. It isn’t much fun showing up to events that are poorly attended and stumping to disinterested audiences. I remember driving all day to New Hampshire to meet with a “crowd” of one person in a coffee shop or spending Labor Day in Iowa to address a tiny rally. The day-to-day positive reinforcement is spotty to say the least.

You believe in your message and hope that it will catch hold and that reporters will share your ideas with others who will then take an interest in you. And if you do start to grow a base of support, you hope that journalists will notice and cover you more.

Instead, many members of the national media feel they have a responsibility to reinforce particular candidates and their “narratives” and dismiss others. They don’t just report on the news; they form it.

That was the case at the 2018 Wing Ding. My team was disappointed that my big debut speech in Clear Lake didn’t get a mention in the press. I didn’t let that discourage me. I traveled to both Iowa and New Hampshire every month from then on. I joked that the early states were like my children: if I visited one, I needed to visit the other one shortly afterward. My work in Iowa paid off in December 2018 when the Selzer Iowa poll included me in its list of candidates. It was the first nationally recognized poll to actually include me, which itself was a big deal after being ignored for months—thank you, Selzer and The Des Moines Register! The numbers were not great: I was dead last of the twenty-one candidates listed, including some people who weren’t running, like Eric Holder. I had the lowest name recognition of any of the twenty-one candidates and was the only one with net unfavorables: of the 17 percent who had heard of me, 12 percent didn’t like me. Zero percent said I was their first choice for president.

But buried in the poll were a couple signs that just about made me jump for joy. Seventy-six percent of those polled said they could consider supporting me or didn’t know, which was comparable to other candidates. And 1 percent of polled caucus goers said I was their second choice. That was the same level of support drawn by established politicians like Kirsten Gillibrand, Jay Inslee, and Eric Swalwell. I figured polling would be the main criterion to eventually make the debates, and now there was a glimmer of hope.

To me, that was all I needed. If there were a few Iowans who were enthusiastic about me, I knew we could find more. But it was going to take a lot of work and ingenuity.