Record for oldest DNA ever sequenced broken by mammoth remains

Credit: Thomas Quine / Flickr

- Scientists extracting DNA from mammoth teeth have set a new record for the oldest DNA ever sequenced.

- The new record holder may also be a member of a new species of mammoth, but that remains to be proven.

- The findings suggest that DNA as old as 2.6 million years old could be decoded.

Analysis of million-year-old mammoth remains has set a new record for the oldest DNA ever sequenced and revealed a potentially new mammoth species. The study containing these findings, published in Nature, sheds new light on the mammoth’s evolutionary history and suggests that even older DNA samples could have survived to the present day.

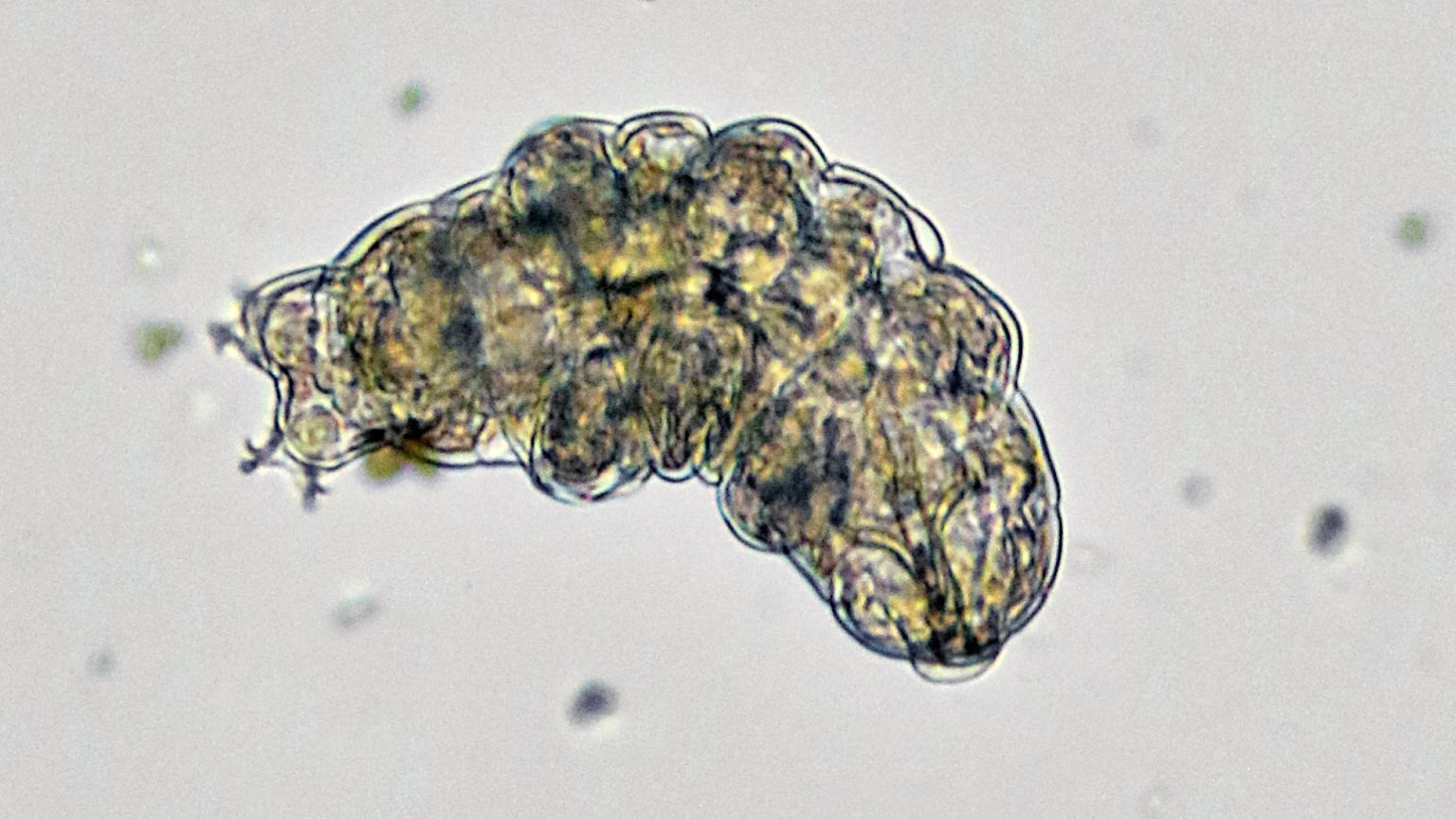

The DNA was taken from three sets of mammoth teeth discovered in Siberia in the 1970s. The three samples, named Krestovka, Adycha, and Chukochya, are too old for carbon dating techniques to be useful. Their ages were instead determined using methods such as radiometric dating.

Krestovka is the oldest of the three, dating back to about 1.1 or 1.2 million years ago. In addition to setting the record for the oldest animal to have DNA sequenced from it, Krestovka appears to be the first known example from a new lineage of mammoth. It seems to belong to another branch of the evolutionary tree that left no living decedents. However, some of its DNA also exists in the Colombian mammoth’s genetics, which raises other questions.

While it is too soon to say that Krestovka is from a new mammoth species, the possibility is there. If it is, then it also suggests that the Columbia mammoth could be a hybrid species between this unknown branch and the woolly mammoth. This would be particularly exciting, as evidence for hybridization creating new species is rare.

Adycha dated back about one million years. It is thought to be a steppe mammoth, a larger, less hairy ancestor of the woolly mammoth. Steppe mammoths lived across Eurasia but were considered to be best suited for warmer climates than Siberia. Some of the DNA fragments also imply that adaptations for surviving in cooler temperatures, revealed in genes related to fat deposits, thermal regulation, and the circadian rhythm, appeared earlier in the evolutionary tree than previously thought.

Chukochya is the youngest of the three. Dated to some point between 500,000 and 800,000 years ago, it was an early example of a woolly mammoth.

DNA breaks down fairly quickly in most environments. Exposure to bacteria, water, ultraviolet light, or enzymes breaks it down. Even in the permafrost, where conditions are more favorable, these factors slowly whittle away at the information until little is left. That makes this find so exciting — it is remarkable that this much information endured a million years in the ground.

The previous record-holder was the DNA of a 750,000-year-old horse found in the permafrost of the Yukon. In principle, it is possible to find DNA as old as the oldest permafrost: 2.6 million years old. Protein sequences last longer; the current record holder is dated back to 3.8 million years but reveal much less information.

While the DNA from these mammoth teeth was quite fragmented, modern technology made putting the pieces together possible. By comparing what remained with the DNA of elephants and younger mammoth samples, the scientists could isolate the fragments that were unique to the specimen.

Ludovic Orlando, the head of the team which held the previous record, expressed his excitement at losing it, “I love this paper. I have been waiting since 2013 [for] our world record for the oldest genome to be broken.”

Not yet. As mentioned, these sequences are incomplete and damaged due to their age. The cloning of mammoths using more complete samples of their DNA is generally thought to be a bit unfeasible. Even if it could be done, there is a question of what you’d do with the animal you’ve created. While some have suggested bringing the mammoths back and putting them in Siberia, the benefits of doing this remain unstated.

However, the findings shine a light on evolutionary paths previously unknown to us and prove that these methods can work on other samples, potentially including even older ones.

So, even if you’re not going to see a cloned mammoth any time soon, you may see a better model of one at the natural history museum and a better picture of how life on Earth, including our species, changes over time in response to shifting environmental factors. It’s a great takeaway from studying some old teeth.