The surprising reason Inca children were drugged before human sacrifice

- Pre-Columbian civilizations like the Incas incorporated drugs in their rituals of human sacrifice.

- Previously, it was assumed the victims of this ritual consumed psychoactive drugs to help them get in touch with the supernatural forces they were about to meet.

- However, a recently published toxicological analysis suggests the drugs were used not to induce visions, but to combat the depression and anxiety one would feel at the prospect of being sacrificed.

In September 1995, explorers Johan Reinhard and Miguel Zárate stumbled upon the mummified body of a teenage Inca girl while scaling the Ampato volcano in southern Peru. A second expedition organized by Reinhard the following month led to the discovery of two more girls. Research indicated they were even younger than their older sister, between six and seven years old.

Evidence suggests these children were the victims of human sacrifices. The volcano on which they were buried, located not far from the city of Arequipa, was revered as the home of some of the most important gods or “huacas” of the Inca Empire. Its original name, “hampattu,” is thought to have derived from the Quechua word for toad, a creature featured prominently in Andean folklore.

The children were buried at heights over five kilometers, an unusual resting place, which further indicates their deaths took place under extraordinary circumstances. They were also surrounded by precious goods that Reinhard and others believe were used as additional offerings, including ceramic vessels, figurines made from gold and silver, and intricately decorated textiles.

Because the Incas did not have a written language, it’s hard to figure out what exactly happened during these human sacrifices. Most of what we know about the ancient practice comes to us from the questionable accounts of Spanish colonizers, who lacked the knowledge necessary to record their observations with the same degree of objectivity we expect from modern-day ethnographers.

Recent studies on human sacrifices in the Inca Empire have resorted to chemistry as a means of testing the hypotheses put forth by excavations and historical documents. This year, an article published in the Journal of Archeological Science shared the results of a comprehensive and highly anticipated toxicological analysis of the mummies recovered from Ampato.

According to the article, which Reinhard co-authored, the Ampato mummies tested positive for chemicals present in coca leaves and ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic drink made from the bark and stem of various tropical plants. These substances were used widely in the Inca Empire and are known today for their euphoric and mind-altering effects.

The idea that Inca children were drugged before they were sacrificed is not new; it has been mentioned in academic literature and was even described, albeit vaguely, by the Spaniards. However, the unprecedentedly precise data gathered by Reinhard’s team suggests that those drugs served a radically different purpose in the ritual than we previously assumed.

The final moments of the Ampato mummies

When the conquistadors invaded the Americas during the 16th century, the Inca Empire had developed from a small regional government into the largest political entity of the pre-Columbian Andes. The Inca state organized numerous religious ceremonies, not only to appease their corresponding huacas but also to assert political dominance over conquered territories.

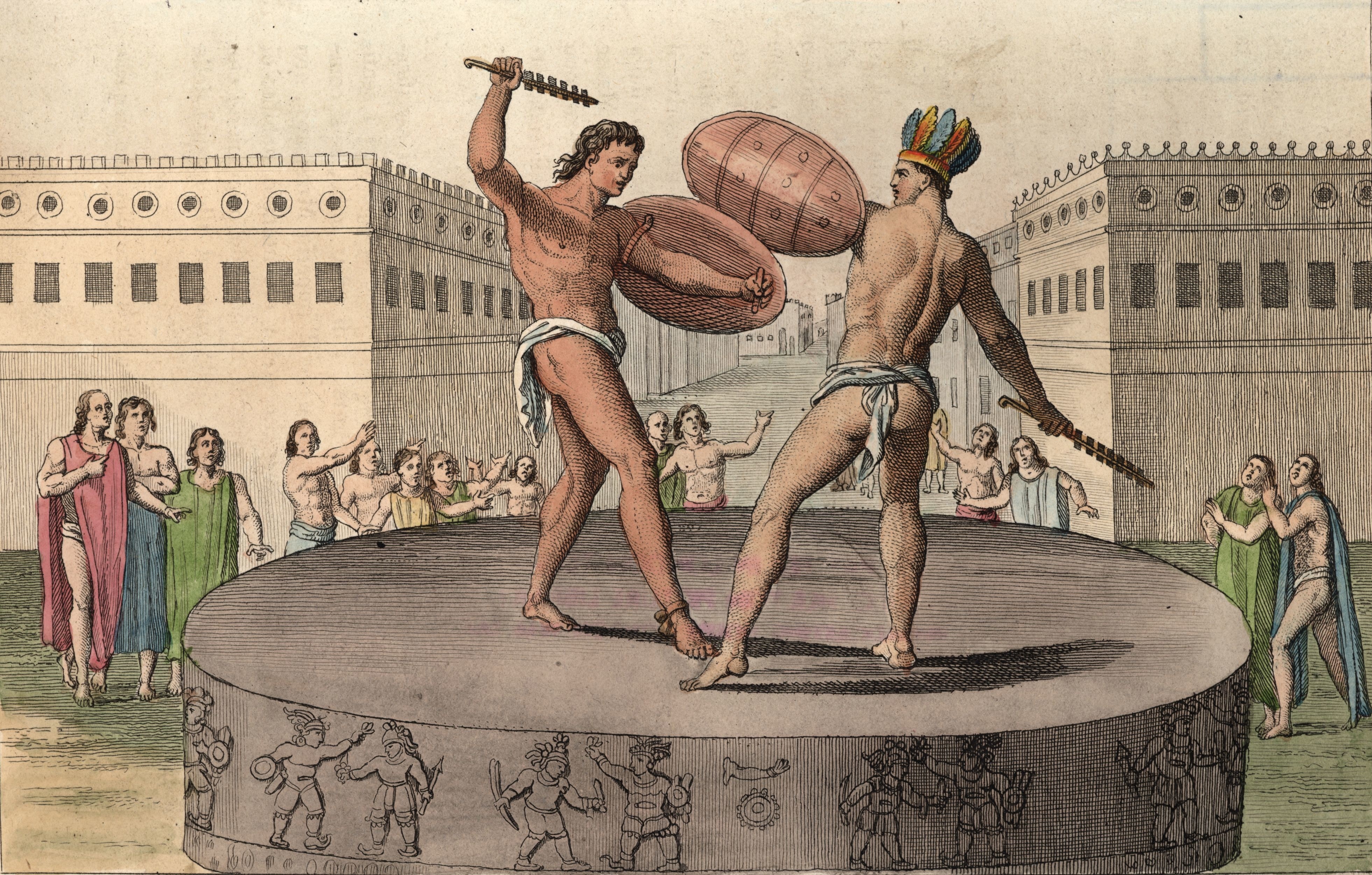

Of these religious ceremonies, the capacocha ranked among the most significant. Capacocha rituals centered on the sacrifice of young women and children, people whom society regarded as unspoiled. Female candidates were selected for their beauty as well as their virginity, and housed in special compounds where they awaited the day they would be sacrificed by the priests.

Others may have been chosen for their disabilities. Studies of rituals performed at a different stratovolcano (Misti) discovered that several victims had curved legs. In the Inca Empire, physical disabilities were seen as evidence of interference from the gods. Those born with such conditions were revered and, consequently, made to play a prominent role during sacrificial rites.

Selected children traveled to the capital city of Cusco to receive an audience with the emperor, a pilgrimage that often took months to complete. From Cusco they were taken to the location of the sacrifice, usually atop a mountain where the huacas dwelt.

Some chroniclers have maintained that the children’s hearts were cut out of their chests, a gruesome image that heavily influenced the way we picture human sacrifice today. The Ampato mummies, however, show no signs of injury. Reinhard’s article suggests that the children were either strangled or buried alive. They even may have died of extreme cold.

Capacocha rituals served different purposes for different parts of the Empire. Local communities organized them to prevent natural disasters like droughts, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. For the Inca state, the ritual helped establish and signify the hierarchy of huacas — no small task, considering there were as many as 475 keeping watch over Cusco alone.

Ayahuasca as an antidepressant

A toxicological analysis of hair and nails from the Ampato mummies betrayed the presence of harmine, a component of ayahuasca that strongly suggests the children were given a form of the hallucinogenic drink during the sacrifice. Coca alkaloids, meanwhile, indicate they had been chewing coca leaves for weeks leading up to their inescapable deaths.

In Inca society, plants with psychotropic properties served a number of cultural, economic, and political purposes. Coca leaves, the source of cocaine, were used as funeral offerings, being buried alongside the deceased and sometimes placed inside their mouths as well. The state, meanwhile, used them as a form of diplomatic gifts as well as payment.

Spanish observers noted that the Incas also relied on coca leaves as a medicine to treat various ailments, including digestive problems, altitude sickness, and mouth ulcers, and also to reduce the feeling of hunger. They also mentioned alcoholic and hallucinogenic drinks, which were used to improve a person’s mood, prepare them for battle, or help them connect with the gods.

Among these drinks was ayahuasca. It is made from Banisteriopsis caapi, a liana plant indigenous to the Amazonian rainforest. Often translated as “liana of the soul” or “liana of the dead,” ayahuasca causes an hallucinogenic state that has been described as a “spiritual” or “near-death experience.”

It is believed that Inca children consumed psychotropic substances in order to get in touch with the supernatural during the moments leading up to their sacrifice. This would make sense considering that, after their deaths, their contemporaries would go on to worship them as mediators between the world of people and the world of huacas.

In reality, however, it seems more likely that the victims were given these drugs to make them more compliant, as well as to help with the anxiety and depression they must have felt upon realizing their days were numbered. Evidence for this is both anecdotal and scientific. For one, several Spanish observers wrote that the drugs were used to dull rather than heighten the senses of the victims.

More importantly, Reinhard’s toxicology report found that the Ampato mummies tested positive for harmine but negative for DMT. Both are components of ayahuasca but produce different effects. DMT is the main psychoactive component of the brew. Harmine, by contrast, blocks the breakdown of serotonin and dopamine. For this reason, it has been used in modern medicine to treat depression.

This, combined with the ecstatic feeling derived from chewing coca leaves, suggests the children were given drugs not to induce visions but improve their mood. “The knowledge of being about to be ritually sacrificed,” Reinhard and his co-authors conclude, “likely produced serious anxiety… the active consumption of Banisteriopsis caapi might have helped keep the victims more accepting of their fate.”