Hopewell: Did a comet destroy one of the biggest ancient trading networks in North America?

- Cosmic airbursts occur when comets explode in the upper layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

- Their disintegration sends forth shockwaves that are known to cause catastrophic damage to the environment.

- Researchers believe such an airburst may have led to the downfall of an ancient Native American trading network.

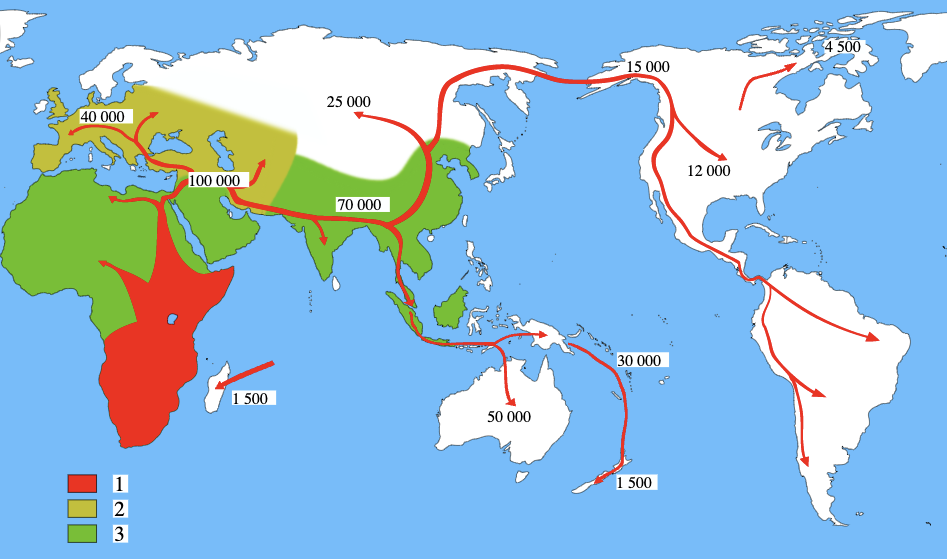

From 100 BC to 500 AD, a network of trade routes connected many Native American communities across North America into a single economic superstructure which is now referred to as the Hopewell tradition. Though Hopewell communities were culturally distinct, their sustained contact with one another led them to adopt a number of uniform practices, archaeological evidence of which helps us determine the tradition’s rise and fall.

Most of what we know about Hopewell communities comes from excavations. They cremated their dead, though important people like hunters were often buried. Hopewell communities were also known for their earthwork structures, specifically their mounds. These “large earthen enclosures,” archaeologist Mark Lynott stated in his book Hopewell Ceremonial Landscapes of Ohio, “appear to have been multi-functional places where people perhaps met for games, ceremonies, rituals, trade, or to share news.”

At the peak of the tradition, Hopewell communities could be found anywhere from North Dakota to Louisiana. Unfortunately, however, the success of this ancient trading network was not to last. In the 1960s, carbon dating showed that the last of the mounds were constructed around 550 AD. After this date, almost every trace of this once prevalent culture — from their tools to their art — seemingly disappears from the archaeological record.

Hopewell vanishes

Several hypotheses were brought forth. One article published in the Central States Archaeological Journal speculated the Hopewell tradition — a non-militant entity created by the voluntary participation of its members — lacked the means to prevent and resolve conflict. Excavations also revealed that many Hopewell villages eventually became surrounded by stockades, a possible sign that their contact with the wider world had been decreasing alongside their trade in exotic goods.

A new theory turned to outer space in search of answers. In February this year, an archaeological study published in the journal Scientific Reports suggested the cultural decline of the Hopewell tradition may have been linked to a cosmic airburst that occurred over the Ohio River valley between 252 and 383 AD. Although the Hopewell communities are thought to have outlived this catastrophic event, their way of life was bound to have changed significantly.

The destructive power of cosmic airbursts

According to the article, cosmic airbursts are created when comet fragments travel through the upper layers of our planet’s atmosphere, where high air pressure releases “a devastating high-energy shockwave over a large area.” Much has been written about the devastating effect asteroid impacts can have on plant and animal life. However, their influence on human communities in particular remains poorly understood.

Most of what we know about the environmental impact of cosmic airbursts comes from studying the last time one is believed to have taken place: the so-called Tunguska event. On June 30, 1908, a 60-meter meteorite exploded high above the Siberian taiga, sending forth a shockwave that knocked over 80 million trees across an area of 2,150 square kilometers. While the handful of eye-witness accounts were initially met with skepticism, researchers eventually managed to corroborate their stories.

Doing so wasn’t easy. The airburst took place at an altitude of at least five kilometers, completely disintegrating the comet before it touched the ground. Unable to discover an impact crater, the scientific community went in search of other, smaller traces of the airburst. Almost a century later, researchers analyzing the soil of a nearby peat bog stumbled upon unusually high concentrations of iridium — an element that’s rare on Earth but relatively common in outer space.

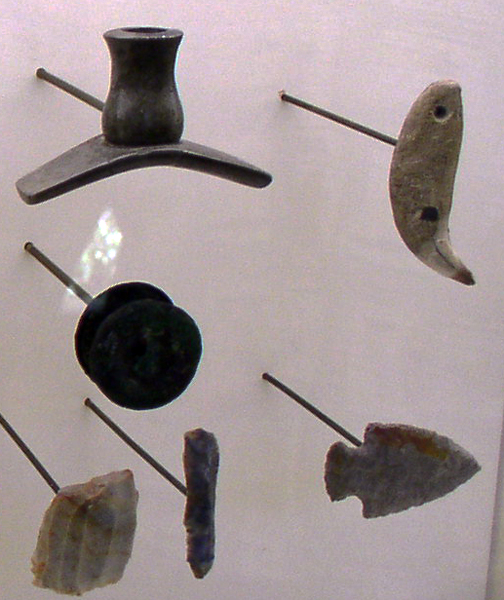

If a cosmic airburst did occur above North America while the Hopewell tradition was still around, it too failed to leave behind an impact crater. Still, archaeological excavations from various Hopewell communities showed that the Ohio River valley contains “an anomalously high concentration and diversity” of meteorites. Evidence of these meteorites survive in the form of fragments, which, at one point, were so abundant that the tradition’s people incorporated them into their jewelry, musical instruments, and burial gifts.

Given that these items were coveted by and frequently traded between communities, however, it is hard to determine where these fragments were originally recovered, let alone whether they came from one or multiple airbursts. The aforementioned study from Scientific Reports, written by a team of geologists and anthropologists at the University of Cincinnati, mapped out the distribution of meteorite fragments across 11 different Hopewell sites and concluded the materials could not be traced back to a single source. Instead, they probably came from “multiple independent” airbursts dated from 252 to 383 AD.

The mysterious fate of the Hopewell tradition

At each site, researchers scanned the sediment for iridium and platinum as well as two other chemical markers of meteorites: iron and silicon. Prior to their study, the sediment at Hopewell sites had scarcely been analyzed. Some sites were revealed to contain higher concentrations of rare earth metals than others, suggesting that the sites with the highest levels of concentration are located “at or near the epicenter” of an airburst.

Given that the environmental destruction at Tunguska was caused by a single airburst, one can only imagine the kind of damage that multiple ones could have brought about in the Ohio River Valley. While we still don’t know just how these airbursts affected life for members of the Hopewell tradition, we do know a thing or two about the way in which these catastrophes affected their culture.

None of the communities that were part of the Hopewell tradition had a writing system, making it difficult for scholars to reconstruct the past as they saw it. Other than the incorporation of rare earth metals into jewelry and instruments, a comet-sized earthwork found near a Hopewell site in Milford, Ohio suggests that the tradition’s people may have put up special structures to commemorate the airburst.

Memory of the catastrophe may also have persisted in the form of oral histories that were passed down from one generation to the next. These memories ended up in the origin stories of a number of Hopewell communities, where they eventually took on anthropomorphized forms. The Myaamia, for example, spoke of an ancient comet called Lenipinšia, which they pictured as a horned serpent dropping rocks as it crossed the sky.

Both the Shawnee and the Haudenosaunee refer to an infamous comet as the Sky Panther — a being endowed with the power to destroy entire forests — and the oral history of the Odawa contains a story about a time when the Sun fell from the sky. If the airburst theory proposed by this new article is correct, myths such as these could be interpreted much more literally than previously assumed.