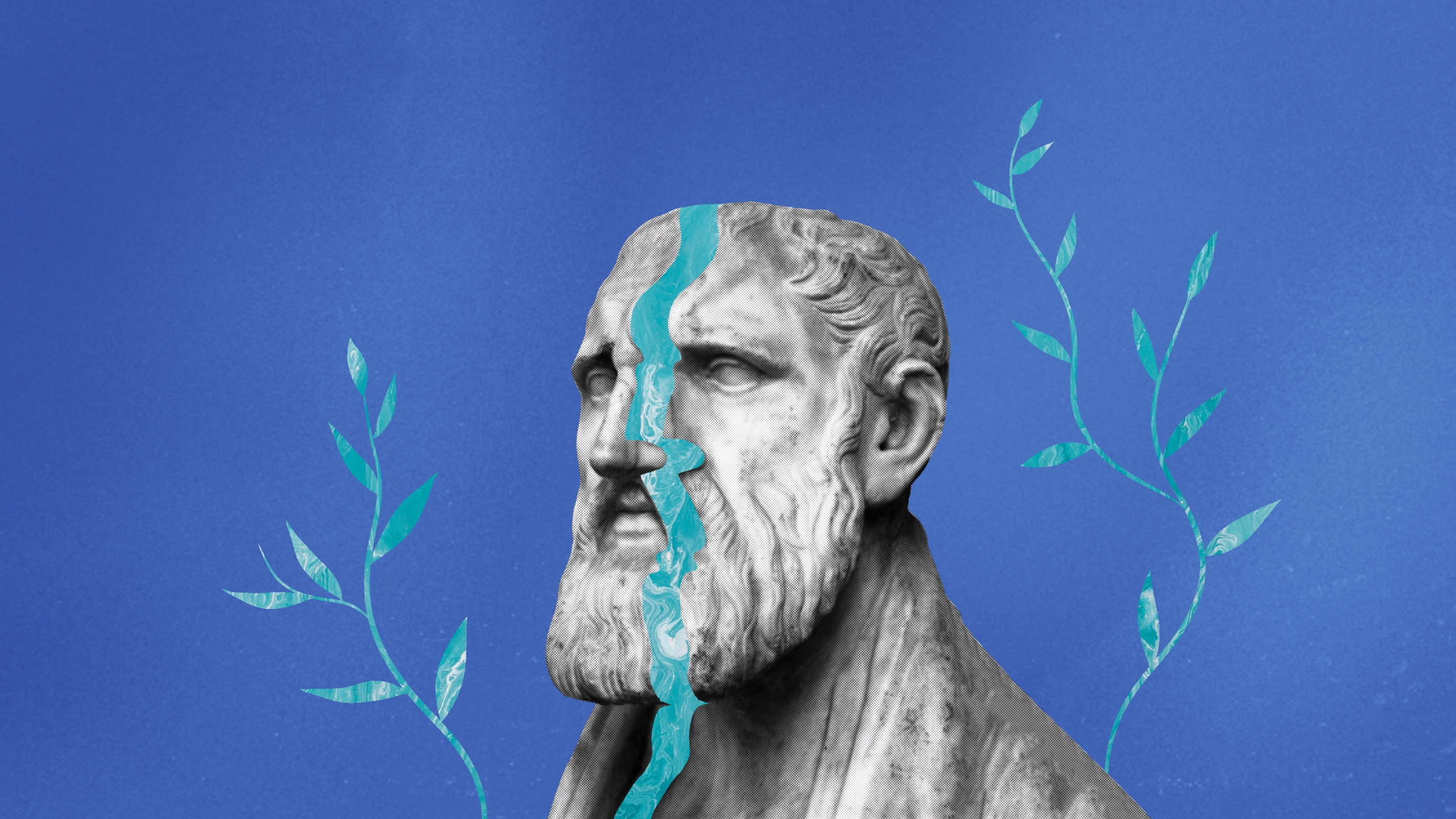

How to rule your emotions like a Stoic philosopher-king

- During Marcus Aurelius’ reign, the Roman Empire confronted war, plague, and rebellion.

- Journaling offered the philosopher-king a daily means to develop his self-awareness and strengthen his ethical resolve.

- Research shows that journaling can help us better regulate our emotions and improve our mental well-being.

Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus — Marcus to his friends and historians — ruled Rome in a time of turmoil. Under his watch, the Antonine plague devastated the Empire. Two frontier wars strained the armed forces and drained the imperial coffers. A trusted general, Avidius Cassius, led a rebellion against him. Topping it off, Marcus himself suffered from ill health, and his son Commodus was the absolute worst.

Despite these challenges, history looks back fondly on Marcus and his leadership. He kept the Empire from fracturing, passed laws to improve the lives of citizens and slaves alike, and may even have sent an embassy to China to establish a trade route centuries before Marco Polo’s famed journey. For his accomplishments, he is considered the last of the Five Good Emperors and a symbol of Rome’s golden era.

How did he manage? As with any historical figure, the answer is multifaceted. His adherence to education, philosophy, and hard work certainly played a role. Another element was his temperament for politics and the law, and, as we’ll see, he enjoyed the occasional stroke of luck. But in my eyes, Marcus’ signature advantage was knowing how to cultivate his emotional intelligence and his ability to tap into it at the critical moment.

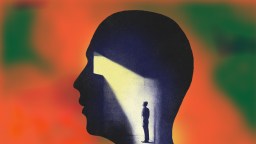

The king and EI

As defined by Daniel Goleman, emotional intelligence (EI) is “the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, and for managing emotions well in ourselves and in our relationships.” Its foundational pillars include such abilities as self-awareness, motivation, emotional self-regulation, and social awareness.

While Marcus wouldn’t have thought in such modern terms, he did understand the value of such abilities in terms of practical ethics. As Christopher Gill, a professor of ancient thought at the University of Exeter, notes: “Self-scrutiny and self-examination were standard features of philosophical practice at this time, and the methods of practical ethics evolved in this period were designed to encourage people to take forward their own self-improvement.”

Marcus’ command of emotional intelligence is clear in his handling of the aforementioned rebellion. In 175 CE, Cassius used a rumor of Marcus’ death to garner support in the Eastern provinces and proclaim himself the emperor. At the time, Marcus was fighting in the north, but when word of the uprising reached him, he made peace with the Germanic tribes and turned his attention eastward. The two would never fight though, as Cassius’ kingly ambitions were cut short by an assassin’s dagger. (Never underestimate the role luck plays in history.)

Like many monarchs before and after, Marcus could have used the opportunity to crush his enemies and violently bring the Eastern provinces to heel. Instead, he showed restraint. He pardoned the wayward general’s co-conspirators and instituted a peace tour. In doing so, he showed incredible self-awareness for a leader in his era, as well as social awareness for how to renew loyalty.

Another potential example may be Marcus’ decision to rule alongside his adoptive brother, Lucius Verus. When the Senate bestowed Marcus the title imperator, the fresh-faced philosopher king refused to accept it unless Lucius was named co-emperor. Now, statesmanship certainly played into his decision. According to historian Frank McLynn, Marcus made the choice as a means to “head off the possibility of a coup by the Ceionius clan jealous that their putative rights to the throne had been ignored.” However, recognizing those emotions in others as well as his own aptitudes — Marcus seemed to only accept the throne out of a sense of duty — seems the result of Marcus’ well-tuned emotional intelligence, too.

Journaling to improve emotional intelligence

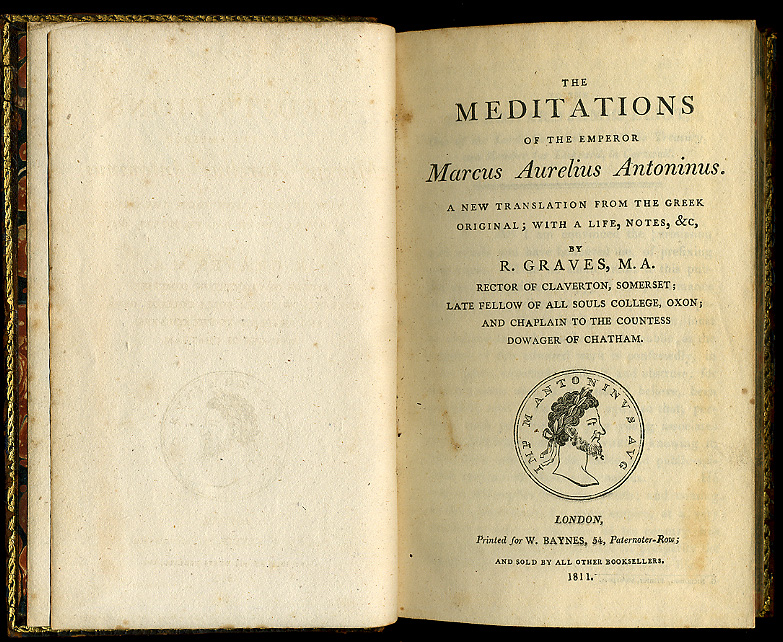

How did Marcus cultivate his EI? One method he used was journaling, and we know this because his notebooks survived him in the form of Meditations.

Today, Meditations is often read as a Stoic text, but evidence suggests that Marcus didn’t write the material to be published or taught. As Gill points out, most of the text appears to be written in no particular order. Themes often repeat themselves, and occasionally Marcus will simply group together quotes from various other authors. These and other signs indicate the work was a personal journal he kept during his European military campaigns.

“It seems likely that Marcus simply wrote down one or two comments at moments of leisure, for instance, at the beginning or end of the day, and the resulting work is the sum of those comments,” Gill writes. “Marcus is writing to examine his inmost thoughts and advise himself how best to live.” In fact: While Marcus never titled the work, its first Greek title was Ta Eis Heauton, which translates as “To Himself.”

This style of journaling has much in common with what Cassandra Worthy, founder and CEO of Change Enthusiasm, refers to as “capturing your emotional data.” In a Big Think+ interview, Worthy shared how she uses her journal to first express, then identify, and finally understand the challenging emotions she may feel on a given day. Once she has accumulated many such data points, she can then review her journal to recognize patterns in her emotional behavior. That improved self-awareness can inform ways for her to bolster her emotional intelligence to better handle similar emotions and situations later on.

“The more that you can capture this emotional energy, you can go back and almost recognize patterns,” Worthy said. “And oftentimes, you can see an action, an activity, or maybe an individual that you’re engaged with that inspires the signaling motion that you’re experiencing most often. You can then paint a picture of a recurring signal when you’re doing a certain thing and that can help you focus attention on that area.”

Consider motivation, another EI ability. Like most people, Marcus had difficulty getting out of bed in the morning, and as the historical examples of Nero and Commodus show us, no one was going to make a Roman emperor do what a Roman emperor didn’t want to. However, facing such tumultuous times, Marcus recognized the need to join the morning larks. In his journal, he provided instructions for doing just that:

“Early in the morning, when you find it so hard to rouse yourself from your sleep, have these thoughts ready at hand: ‘I am rising to do the work of a human being. Why, then, am I so irritable if I am going out to do what I was born to do and what I was brought into this world for? Or was I created for this, to lie in bed and warm myself under the bedclothes?’” (5.1)

Given his historical accomplishments, it seems to have worked.

Meditations and more

In addition to exploring his emotional intelligence, Marcus may have received additional benefits from his journaling habit. Modern research into the practice suggests that expressive writing — that is, journaling to explore your emotions and feelings rather than a diary recording daily events — may boost well-being.

An overview of the clinical research published in Advances in Psychiatric Treatment found the practice to be associated with improved mood, greater psychological well-being, and even better health outcomes, such as reduced blood pressure. While the researchers could not determine an exact cause for these benefits, they hypothesize that journaling helps people develop a coherent narrative that “helps to reorganize and structure traumatic memories, resulting in more adaptive internal schemas.”

Other studies have shown journaling to offer other benefits. For example, journaling about emotions and how we think about them can:

- Heightened self-efficacy in college students.

- Decrease rumination to help us sleep better.

- Reduce stress by helping us prioritize problems, fears, and concerns.

- Improve mental distress and well-being by building emotional resilience and reducing depressive symptoms.

“But if you look carefully, you will generally observe this further point, that what benefits one person also brings benefits to others.”

– Marcus Aurelius, Mediations (6.45)

Emotional intelligence isn’t built in a day

If you are looking to take up journaling, here are some helpful tips and ways to get the most from the practice:

Start small

You don’t need to journal for hours every day until you’ve produced your own Meditations. Trying to take on too much will make journaling another source of frustration and negative emotions, as opposed to an activity for decluttering your emotions and cultivating self-awareness.

Worthy recommends starting small. Set a goal of journaling at the same time every day for 30 days, but limit yourself to writing for five minutes or even a single sentence. This strategy can help you build the habit and momentum. After that, you can then up the time to, say, 10 minutes or a couple of sentences. And so on.

Importantly, you can still reap benefits during this habit-building phase. Many of the studies cited above only asked participants to write expressively for about 15 minutes for a couple weeks, and yet they still showed moderate results. As the old proverb goes: “Rome wasn’t built in a day,” but as James Clear reminds us, “They were laying bricks every hour.”

Ask what, not why

Self-reflection can have its dark side, too. Organizational psychologist Tasha Eurich notes that trying to understand why we feel or act a certain way can lead us to incorrect understandings. For instance, a parent reflecting on an incident in which he yelled at his child may assume he did so because he is a bad person — rather than the more likely answer that he is a good person suffering from a bad week.

That false reasoning can trigger a destructive cycle of rumination and self-criticism. It can further cloud our self-awareness, distort our journaling data, and make us less capable of emotional regulation. We are, after all, not entirely rational even at the best of times, and exploring painful emotions is hardly the best of times.

To help you short-circuit this tendency, Eurich recommends you forego exploring emotional “why” questions. As she writes in the Harvard Business Review: “As it turns out, “why” is a surprisingly ineffective self-awareness question. Research has shown that we simply do not have access to many of the unconscious thoughts, feelings, and motives we’re searching for. And because so much is trapped outside of our conscious awareness, we tend to invent answers that feel true but are often wrong.”

Eurich suggests you focus on “what” questions instead. For example, rather than starting a journal entry with the question, “Why did I yell at my kid?” the parent above would be better served asking: “What about the situation led you to become so angry with your child? What can you do moving forward to prevent a similar situation from occurring?” This wording presents the incident from an emotional distance, which can help you gather better data for more efficacious problem-solving.

Tap into the universal “you”

Another way to get emotional distance and prevent journaling from reinforcing negative emotions is to engage in distanced self-talk. Distanced self-talk is when you talk (or write) to yourself as though speaking (or writing) to another person.

In a study performed by psychologist Ethan Kross, participants were asked to write about their fears and concerns before giving a public address. One group was instructed to write using the first-person “I” while the other group wrote using the second-person “you.” Kross’s results showed that participants in the “you” group experienced less embarrassment and ruminated less about their performances afterward.

“There is a potent psychological comfort that comes from normalizing experiences, from knowing that what you’re experiencing isn’t unique to you, but rather something everyone experiences,” Kross writes in his book Chatter. Writing from that universal “you” perspective can help in that normalizing process. Marcus used this technique himself. As we’ve established, Meditations was likely written for the philosopher king’s own edification; however, most of the work is written in the second-person perspective.

Consider this EI-elevating piece of advice: “Confine your attention to the present time. Learn to recognize what is happening to yourself or another. […] Let the wrong committed by another remain where it first arose.” (7.29)

Make it your own

Of course, no matter how helpful a practice may be, it won’t do you much good if you never engage. To help with that engagement, bring to your journaling practice your own interests and needs, and make it your own.

Try dabbling in gratitude journaling. Write in quotes that inspire or challenge you. Include drawings and personal accounts for preservation. Write stream-of-consciousness and get messy, or slow down and write measured details. Borrow from Meditations and other famous journals but don’t try to slavishly follow their example.

The point is to give yourself the time you need to express and reflect upon your emotions and needs, so you can use that information to build the life you want.

Or as Marcus reminds us (and himself): “So constantly grant yourself this retreat and so renew yourself; but keep within you concise and basic precepts that will be enough, at first encounter, to cleanse you from all distress and send you back without discontent to the life to which you will return.” (4.3)

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Cassandra Worthy full class for your organization, request a demo.

Author’s Note: All quotes from Meditations come from Robin Hard’s translation of the text, published by Oxford University Press. Christopher Gill’s quotes come from his introduction to the 1st edition.