The Yerkes-Dodson law: This graph will change your relationship with stress

- Stress is popularly perceived as the silent killer, but not all stress is harmful.

- Eustress can motivate us to accomplish goals and perform well.

- The Yerkes-Dodson law shows how we might tap into this good stress to live more accomplished and mentally sound lives.

Stress has received a bad rap lately. Far from a mental gremlin, this emotional state is your natural response to a stressor or threat. It floods your body with hormones that provide the burst of energy and focus you need to react in a clutch moment or dangerous situation.

Unfortunately, that hormonal mixture contains some high-octane chemicals, such as cortisol and adrenaline. The longer your body holds on to these, the more wear and tear is done to it.

A stressful day can end in fatigue, muscle tension, or a pounding headache. A stressful week grinds on your mood to leave you sad, anxious, irritable, restless, burned out, or all of the above simultaneously. Should your stress become chronic, it can do serious damage in the form of social withdrawal and physical ailments such as stroke and cardiovascular disease.

These facts have earned stress the nickname “the silent killer” — a characterization that’s less life-saving evolutionary response and more serial strangler.

And while this silent killer perception isn’t entirely wrong, it does miss the nuances of our affinity for stress. That being, not all stress is bad stress. Some stress, in particular eustress, can be an important part of living a productive, engaging life.

That’s what two psychologists learned when they decided to torture Japanese dancing mice in the name of science.

Of mice and menacing choices

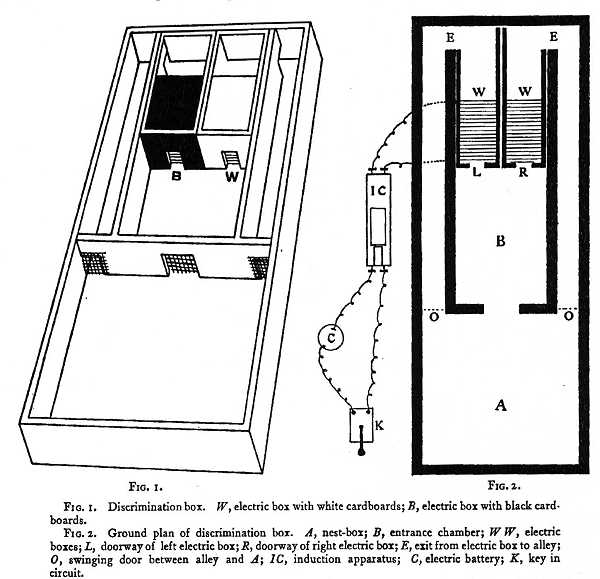

In a famous 1908 paper, Robert M. Yerkes and John D. Dodson investigated habit formation by placing mice in an experiment box. The box contained a nest and two chambers, a black one and a white one.

When forced out of the nest, the mice had to choose either the black chamber or the white one as a means to return. The black chamber delivered a “disagreeable” electric shock to any mouse foolish enough to enter, while the white one let them pass unassailed. (The Animal Welfare Act was still a few decades out.)

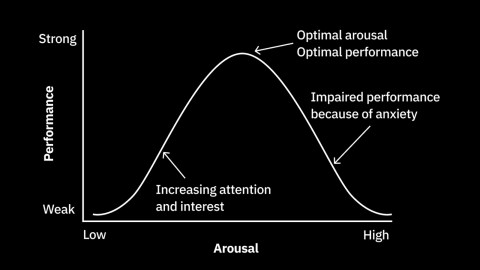

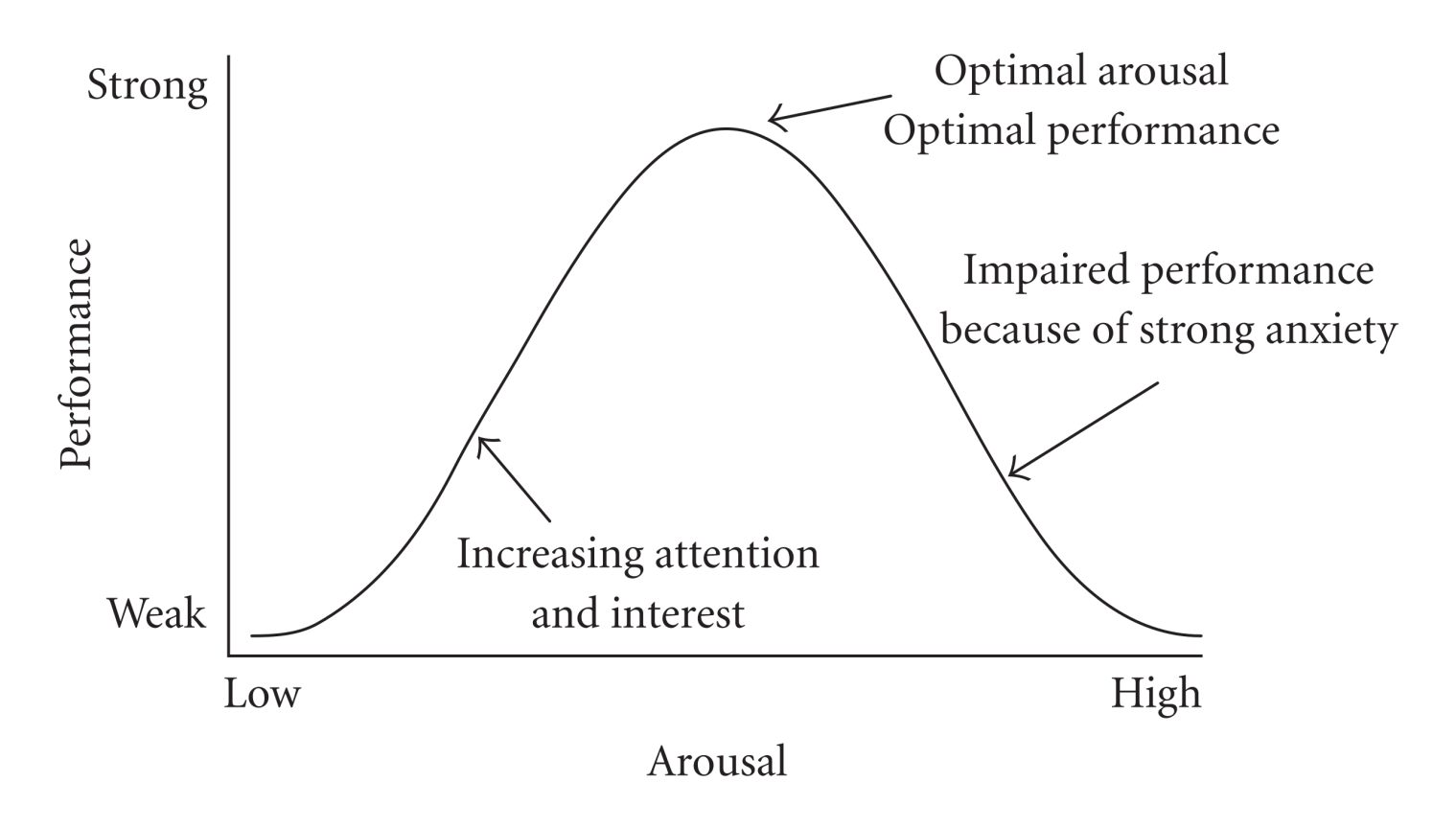

Yerkes and Dodson then varied the shock and brightness levels of the chambers to determine when habit formation proved difficult. They discovered that the mice’s performance increased with “cognitive arousal” (that is, stress plus motivation) but only up to a certain point. Afterward, the mice’s performance tapered off.

When their findings are charted on a graph, it’s essentially the Goldilocks story told as a bell curve. The bottom left of the curve represents low stress but also low performance. Too cold. As the mice move along the x-axis, their stress increases steadily but their performance increases in tandem until reaching the peak. Here, stress and performance are just right. Adding more stress degrades performance. Too hot.

Today, this graph is known as the Yerkes-Dodson law or the arousal-performance curve.

Eustress for success

While there’s no universal definition of stress — it’s a highly subjective and personal sensation — research does suggest that we experience three different types, or levels, of the emotional state: eustress, distress, and sustress. And the Yerkes-Dodson law shows us why that is.

In the middle of the curve, we have eustress. It’s the low-to-moderate amount of stress that leads to arousal. In this context, as in Yerkes and Dodson’s experiment, arousal doesn’t mean a kind of erotic excitement (though it doesn’t rule it out either). Rather, it’s the combination of stress and motivation that propels us to accomplish a task or rise to a challenge. We experience it less as a strain and more as attentiveness galvanized by a crackle of positive energy.

As neuroscientist Amishi Jha explains in her book, Peak: “This type of ‘good’ stress […] is a powerful engine for performance, all the way up to the very top of that chart, where we reach the optimum level (what I affectionately call the ‘sweet spot’). [Here], stress is a positive motivator, something that drives and focuses us.”

If our stress tips beyond the sweet spot, we enter distress — what we typically think of as stress. It’s that high-potency agitation that arises thanks to emergencies, physical threats, overly demanding work, trouble at home, or procrastinating until the do-or-die moment. While useful in an emergency when you need to act quickly, distress can degrade your performance and well-being the more acute it becomes and the longer it sticks around.

Throttle down your stress, and you reach sustress. This is the low-potency stress you feel when you have a deadline that’s several weeks out. Yeah, you could work on the project, but you could just as easily spend the day binging a favorite TV show or window shopping aimlessly through the downtown. Relaxing but weak fuel for performance.

Of course, as with any psychological phenomenon, it’s not always this straightforward. The shape of the curve can vary depending on the difficulty of the task, your skill level, and your familiarity with it. Even mice, Yerkes and Dodson found, can perform well under distress assuming the task is very simple.

However, the Yerkes-Dodson law does provide a useful shorthand for understanding how our minds and bodies relate to and handle stress.

Sometimes stress is more

By this point, you’re probably wondering what a century-old session of animal mistreatment has to do with your stress management. You are, after all, a human and not a mouse stuck in a Skinner box. Fair point.

That same question has prompted researchers to study eustress in our species — albeit without resorting to Saw-inspired experiment boxes — and they’ve found evidence that it works for us, too.

For example, a study published in Psychiatry Research reviewed data from the Human Connectome Project, which looks to map the human brain and understand its relationship to our behaviors. Sampling questionnaires from 1,200 young adults, its researchers looked at reported levels of stress and negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and attention problems. They then compared those to the young adults’ scores on neurocognitive tests.

They discovered that young adults who reported low-to-moderate levels of stress saw psychological benefits. Their findings lead them to suggest that eustress acts as a kind of stress inoculant, potentially making people more resilient to distress and other mental health disorders.

“If you’re in an environment where you have some level of stress, you may develop coping mechanisms that will allow you to become a more efficient and effective worker and organize yourself in a way that will help you perform,” Assaf Oshri, lead author of the study and an associate professor in the College of Family and Consumer Sciences, said in a press release.

The cognitive benefits extend beyond emotional resilience, too. In their book Uncommon Sense Teaching, authors Barbara Oakley, Beth Rogowsky, and Terrence Sejnowski point to research showing that short hits of eustress can improve cognition, working memory, and physical strength in students.

The authors note that these short bursts — what they call transient stress — release adrenaline and cortisol in amounts that enhance connections between neurons without reaching toxic-level doses. Those neural connections may be why people can recall information they learned for a presentation in a packed auditorium years after they graduate.

Finding your stressful sweet spot

As mentioned, stress is a very personal sensation. What stresses you out and the degree to which you find it stressful will vary greatly from others. That means there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to stress management. There are, however, some general guidelines.

If you’re stuck in the sustress doldrums, try seeking out a challenge. This challenge may be related to your career, a hobby, or an exercise goal. What’s important is that it motivates you to engage. Setting goals, making them time-sensitive, and making yourself accountable to others are good ways to pump up the healthy stress — assuming you set realistic goals and deadlines.

When it comes to eustress, remember that you can have too much of a good thing. As Jha writes: “Even if stress begins as motivating or productive, the longer we’re under high-demand conditions, the more that ongoing stress is going to affect us. We’ll start to tip over the optimum stress point and drop down the far side of the stress curve. We rapidly lose any benefits from the stress we’re experiencing, and it becomes a corrosive, degrading force on our attention.”

If you’re chronically distressed, then you need to find reliable ways to release the pressure. While that may sound like a prescription for TV, video games, and a stiff drink or three, it’s not. Those activities are fine in moderation, but research has shown that inactive approaches to stress management don’t relieve stress as well as we think. In fact, they run the risk of increasing your stress if you overindulge to the point of draining time and energy from more active pursuits.

Instead, try adopting a life-affirming stress management style. According to psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar, that means pursuits that target the spiritual, physical, intellectual, relational, and emotional aspects of your life.

When your pursuits foster these aspects, Ben-Shahar argues, they help you become antifragile. This means you can bounce back from painful and distressing emotions faster and more effectively. The concept is not only in line with the Psychiatry Research study but may also broaden your personal arousal-performance curve, creating a larger range in which challenges and struggles fuel you.

“Learning to accept and even embrace painful emotions is an important part of a happy life,” Ben-Shahar told us in an interview. “Rather, happiness resides on a continuum. It’s a life-long journey, and knowing that, we can have realistic rather than unrealistic expectations about what is possible.”

The same is true for stress in all its varieties.

Learn more with Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. Request a demo today.