Utopia is Creepy: The Agreeable Internet Leaves Us Unchallenged, Makes Us Unchallenging

I wonder what Arthur Koestler would think of Google.

The Hungarian writer’s 1967 book, The Ghost in the Machine, is an elegant takedown of Cartesian philosophy. Koestler believed the feeling of dualism arises from what he termed a holon—the mind is, simultaneously, a part and a whole. The brain, he argues, is the outcome of an array of forces, including the environment, habitual patterns, and language. For the holon to function, he writes, it must be self-regulated:

In other words, its operations must be guided, on the one hand, by its own fixed canon of rules and on the other hand by points from a variable environment. Thus there must be a constant flow of information concerning the progress of the operation back to the centre which controls it; and the controlling centre must constantly adjust the course of the operation according to the information fed back to it.

Koestler was alive long enough—he committed suicide in 1983, following a fight with Parkinson’s disease and terminal leukemia—to contemplate the role of computers. Yet our dependency on automation is changing not only the ways we interact; outsourcing memory to Google is changing the physical structure of our brains. How would the holon fare in this new world?

Koestler might not be able to speculate, but we do have Nicholas Carr. The author of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated The Shallows has just released a collection of blog posts, essays, and articles called Utopia is Creepy. While he is in no way anti-technology, he recently told me that we have come to an “intersection of technology with human nature in a way that technology has not been designed to deal with.”

That comes down to how the chemical reactions and motor properties of our physical bodies are not attuned to the attentional demands placed on us by the algorithms on our devices. We don’t even have, he says:

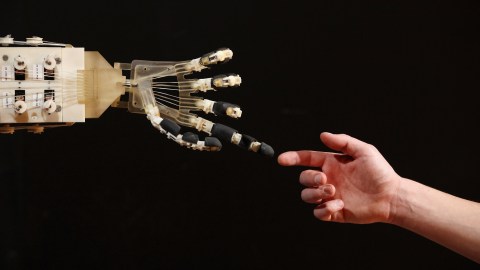

a very good language for talking about the physical nature of existence. And so when a computer comes along—a screen—that presents us with a two-dimensional world that isn’t very physically engaging and starves many of our senses, we nevertheless rush to do things through it. We don’t think about the subtle physical qualities, the tactile qualities we might be losing.

Take Google, a company Carr covers extensively. Have a question? The answer is always seconds away. It’s not convenience factor that’s the major problem; it’s co-dependency. This process began, Carr says, when we started using computers as mediums instead of tools. Our media encloses us, creating a new environment to navigate. Yet this environment, the one Koestler knew necessary for interaction, is virtual. And when the algorithms behind the software are invisible, our consciousness is subjected to the companies writing the code.

Consider exploration, one of humanity’s great evolutionary triumphs. Our brain’s seeking system, as coined by Estonian-born neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp, is responsible for the motivation behind exploring our environment. This, of course, involves getting lost. Interacting with foreign territories is both exciting and educational, including the fear that tags along. Navigating while staring at a screen (or listening to directions) strips away the tactile sense of place. Carr told me,

When we navigate with our senses, we’re engaging our entire body. We’re learning very deeply about the place we’re in. When we simply turn on Google Maps or our dashboard GPS, we can get from one place to another very quickly but we’re starving ourselves of the rich physical quality of being in a place and figuring out how to go from one place to another—figuring out the terrain that we’re in.

Dealing with the environment is only one duty of the holon. Patterns are another; habit formation involves memory. This is where Carr’s writing is most eloquent. At the end of The Shallows he realized that offloading memory and information to his computer was stripping away an ability to develop higher-order emotions such as empathy and compassion. It also damages intelligence. Reaching into our pocket for every question, he says,

does not free us to have deeper thoughts. It’s pretty clear that the way we gain the ability to think deeply and have creative and interesting thoughts is by knowing a lot of stuff. The better stocked your own mind is with lots of knowledge, that’s within you and you’ve made your own through long-term memory consolidation—the more of that you have, then when you get a new piece of information, you can fit it into this much broader context.

Technology companies are resistant to skepticism, however. One of Carr’s scariest findings during his research of his book, The Glass Cage, is automation bias: the speed with which humans grant authority to computers. With specialized media feeds catering to personal tastes and filtering trigger warnings, the online world is very unlike the actual world, in which confrontation is inevitable, and more like, well, utopia. What’s creepy is how little utopia conforms to the reality of biology.

One of my favorite posts in his collection, which was amassed from over a decade of writing on his site, Rough Type, discusses Facebook’s first television advertisement. What is absent is loudest: computers. The ad—which Carr writes in characteristically humorous fashion: “If Terrence Malick were given a lobotomy, forced to smoke seven joints in rapid succession, and ordered to make the worst TV advertisement the world has ever seen, this is the ad he would have produced”—is focused purely on real world phenomena. Everything is bright, shining…illusory, like a swing set in a late-night erectile dysfunction infomercial.

This is what happens when a tool becomes a medium. Carr is fond of quoting Marshall McLuhan, a man who understood how various forms of media act as extensions of our physical bodies. When driving, for example, the contour and textures of road are ‘felt’ by the boundaries of your car; a pencil becomes an extension of your arm, which is an extension of your mind. When the media becomes invisible—when Facebook and Google are so woven into the fabric of everyday life that functioning without them seems impossible—you’re susceptible to the will of software designers and the products and ideas they peddle.

This, Carr believes, has the potential to make life less fulfilling. Humans evolved as “physical creatures adapted to a physical world.” When our sense of social proprioception dissipates—when the map becomes the territory—we not only lose structural and intellectual talents, we also lose the satisfaction that arises from actively engaging with our environment. In other words, he concludes, we become “supplicants to the company writing the software.”

And that loss is not only individual. One big question regarding artificial intelligence is morality. Take self-driving cars. Who writes the moral code of this new driving environment? The car companies, the insurance companies, the government? Religions are structured like corporate institutions, in part, due to their monopoly on ethics. Even the bombastic debate between Tim Kaine and Mike Pence fell to a hush when religious ethics were discussed, such reverence do we pay to the supposed overseers of human morality.

Obviously there is no easy solution. Avoiding tough questions is not going to facilitate active engagement in deciding how we move forward from here, however. Carr has written an incredible body of work pondering such topics; Utopia is Creepy is a wonderful collection of what happens when our humanness collides with the illusory notion of perpetual progress—what occurs when these “meat sacks,” as Vedic philosophers like to call our bodies, get lost in the dazzling Net of Indra. Everywhere we turn we see ourselves reflected in the jewels. We take an infinite stream of selfies while never stopping to realize the entire web is nothing but a dream.

—

Derek Beres is working on his new book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health (Carrel/Skyhorse, Spring 2017). He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.