There are two kinds of Metaverse. Only one will inherit the Earth

- Virtual reality has advanced tremendously, but the technology is fundamentally flawed.

- We have a deeply human aversion to being cut off from our surroundings, and it will be nearly impossible for VR to overcome that.

- Augmented reality seamlessly integrates the real and virtual, which is why the Metaverse will be dominated by AR.

The most polarizing word in technology right now is Metaverse. There are those who are convinced it is the future of society, like Mark Zuckerberg, who is such a believer he renamed Facebook in its honor. Other tech moguls are less impressed. Elon Musk, for example, recently said he is unable to see a compelling use case for the Metaverse and expressed colorfully, “I don’t see someone strapping a frigging screen to their face all day.”

The truth is, they are both correct.

The Metaverse is the future of technology and will transform society over the next decade. On the other hand, very few people will use VR headsets for hours each day other than hardcore gamers and socializing teens. The disconnect is because the word Metaverse means different things to different people, creating confusion in the market.

To solve this, we need to make our definitions more specific, as we are really talking about two very different concepts: the Virtual Metaverse and the Augmented Metaverse, each of which will have different rates of acceptance and profoundly different impacts on society.

But first, what is a Metaverse?

Personally, I define Metaverse as a persistent and immersive simulated world that is experienced in the first person by large groups of simultaneous users who share a strong sense of mutual presence. If you do not achieve the underlined words (persistent, immersive, first person, simultaneous, and presence), it’s probably not a Metaverse.

Still, by this definition, the Metaverse currently exists in platforms like Minecraft and Roblox, which are massively popular but certainly not transformative to society. If you want to carve out gaming-specificworlds, you can add the phrase “general purpose” to the definition, but that still doesn’t justify the hype. After all, the main difference between Minecraft and the avatar-based worlds that Metaverse companies are pitching is better graphics and the use of VR headsets.

VR vs. AR

As I will describe below, the Virtual Metaverse(that is, avatar-based VR worlds ) will be increasingly popular but restricted to limited duration uses. The Augmented Metaverse, on the other hand (that is, the merger of real and virtual worlds into a single immersive and unified reality) will touch every person on the planet and will rapidly transform society. It is the Augmented Metaverse that is the future of technology.

To explain why I am so convinced that AR (not VR) will inherit the earth, I would like to jump back to an experience I had in 1991. I was a grad student at Stanford who was lucky enough to land a gig doing virtual reality research at NASA. My first effort was working with early vision systems, studying how to model interocular distance (the distance between your eyes) to optimize depth perception. While this resulted in a couple of mildly interesting papers during the early days of VR, the impact of that study on my understanding of immersive technologies had nothing to do with the academic results.

Instead, the impact came from the countless hours I had to endure writing code and testing depth perception using a variety of early VR hardware. As someone who truly believed in the potential of virtual reality during those early days, I found the experience somewhat miserable. It wasn’t because of the low fidelity — for I grew up at a time when Pong and Space Invaders were cutting edge — so the fidelity of VR hardware in the early 1990s seemed impressive to me. It also wasn’t because of the size and weight of the hardware, as I knew that would improve.

No, I found the VR experience miserable because it felt confining and claustrophobic to have a scuba-mask on my face for any extended period. But here’s the thing: Even when I used early 3D glasses (that is, shuttering glasses for viewing 3D on flat monitors), the confining experience didn’t go away. That’s because I still had to keep my gaze forward, as if wearing blinders to the real world. It made me want to pull the blinders off and allow the power of virtual reality to be integrated into my real physical surroundings.

This sent me down a path in 1992 to develop the Virtual Fixtures system for the U.S. Air Force, an immersive platform that enabled users to interact with virtual objects integrated into their first-person perception of a real environment. This was before phrases like “augmented reality” or “mixed reality” were in use, but even in those early days, as I observed users enthusiastically experience the prototype system, I became convinced that the future of computing would be a merger of real and virtual content displayed all around us. I also became convinced that purely virtual experiences within enclosed headsets would be limited to short duration activities.

Why VR is fundamentally flawed

The hardware for virtual reality is now drastically cheaper, smaller, and lighter and has much higher fidelity. The software is better too, running on computers that are thousands of times faster with powerful GPUs that couldn’t have been imagined in the 1990s. And yet, the same problems I experienced three decades ago still exist. The issue was never fidelity; instead, it was the deeply human aversion to feeling cut off from your surroundings. Ultimately, that is the real barrier to purely virtual worlds becoming ubiquitous in our lives. The experience is just not natural.

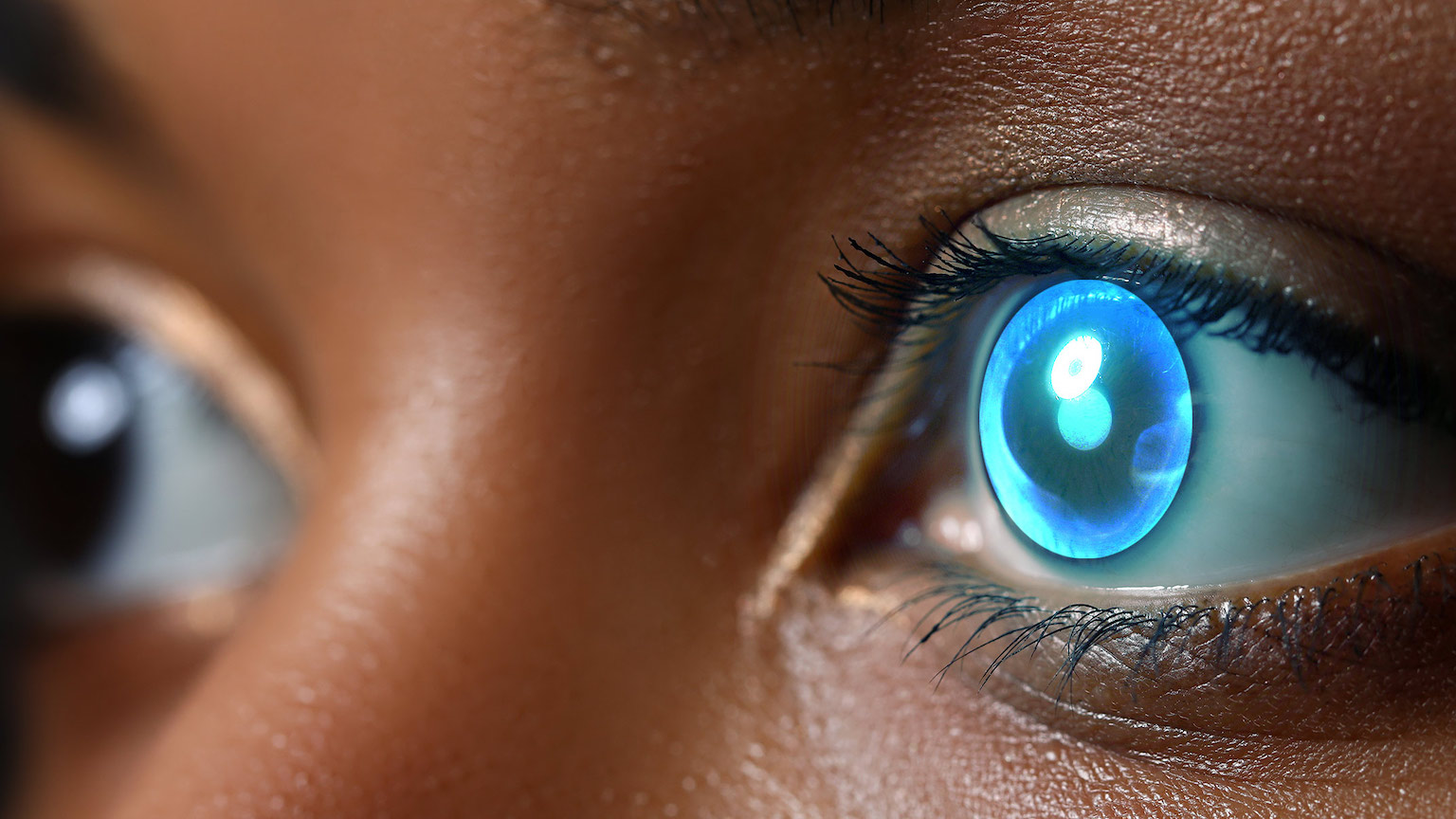

Which is why the metaverse, when broadly adopted, will be an augmented world accessed using see-through lenses. This will hold true even though virtual reality hardware will offer higher fidelity, reaching photorealistic levels. But again, fidelity is not the factor that will drive broad adoption. Instead, adoption will follow the technology that offers the most natural experience to the human perceptual system. And the most natural way to present digital content to the human organism is by integrating it directly into our physical surroundings.

Of course, a minimum level of fidelity is required, but what is far more important is achieving perceptual consistency. By this I mean that all sensory signals (sight, sound, touch, and motion) are aligned to feed a single mental model of the world in your brain. With augmented reality, this can be achieved with relatively low fidelity, so long as virtual elements are spatially and temporally registered to your surroundings in a convincing way. And because our sense of distance (depth perception) is relatively course, it is not hard for this to be convincing.

But for virtual reality, providing a unified sensory model of the world is much harder. This might sound surprising because it is far easier for VR hardware to provide high fidelity visuals. But that is not the problem. The problem is your body. Unless you are using elaborate and impractical hardware, your body will be sitting or standing still while most virtual experiences involve motion. This inconsistency forces your brain to build and maintain two separate models of your world — one for your real surroundings and one for the virtual world that is presented in your headset.

When I say this, many people push back, forgetting that regardless of what is happening in their headset, their brain still maintains a model of their body sitting on their chair, facing a particular direction in a particular room, with their feet touching the floor. Because of this perceptual inconsistency, your brain is forced to maintain two mental models, and you get the same uncomfortable feeling of being cut off from the world that I experienced 30 years ago. This is true even if the graphical fidelity of the virtual world is flawless. There are ways to reduce the effect, but it is only when you merge real and virtual worlds into a single consistent experience — that is, foster a unified mental model — that this truly gets resolved.

The Augmented Metaverse will inherit the Earth

Augmented reality will not only overshadow virtual reality as our primary gateway to the metaverse, but it will also replace the current ecosystem of phones and desktops as our primary interface to digital content. After all, walking down the street with your neck bent, staring at a phone in your hand is not the most natural way to present content to the human perceptual system. Augmented reality is, which is why I believe that within ten years, AR hardware and software will become the dominant platform, overshadowing phones and desktops in our lives.

This will unleash amazing opportunities for artists, designers, entertainers, and educators, as they are suddenly able to embellish our world in ways that defy constraint (see Metaverse 2030 for fun examples). AR will also give us superpowers, enabling us to alter our world with a glance or gesture. And it will feel deeply real, so long as designers focus on consistent perceptual signals feeding our brains and worry less about absolute fidelity. This principle was such an impactful revelation to me when I first started working on AR and VR that I gave it a name, calling it perceptual design.

As for what the future holds, I believe the vision portrayed by many Metaverse companies of a world filled with cartoonish avatars is misleading. Yes, virtual worlds for socializing will become quite popular, but it will not be the means through which immersive media transforms society. The true Metaverse — the one that becomes the central platform of our lives — will be an augmented world. If we do it right, it will be magical, and it will be everywhere.