After oil and gas, Europe is now running out of wind

- Europe’s energy crisis could be an opportunity to accelerate the switch to renewables.

- However, there’s a problem with wind and solar energy: They’re not constant.

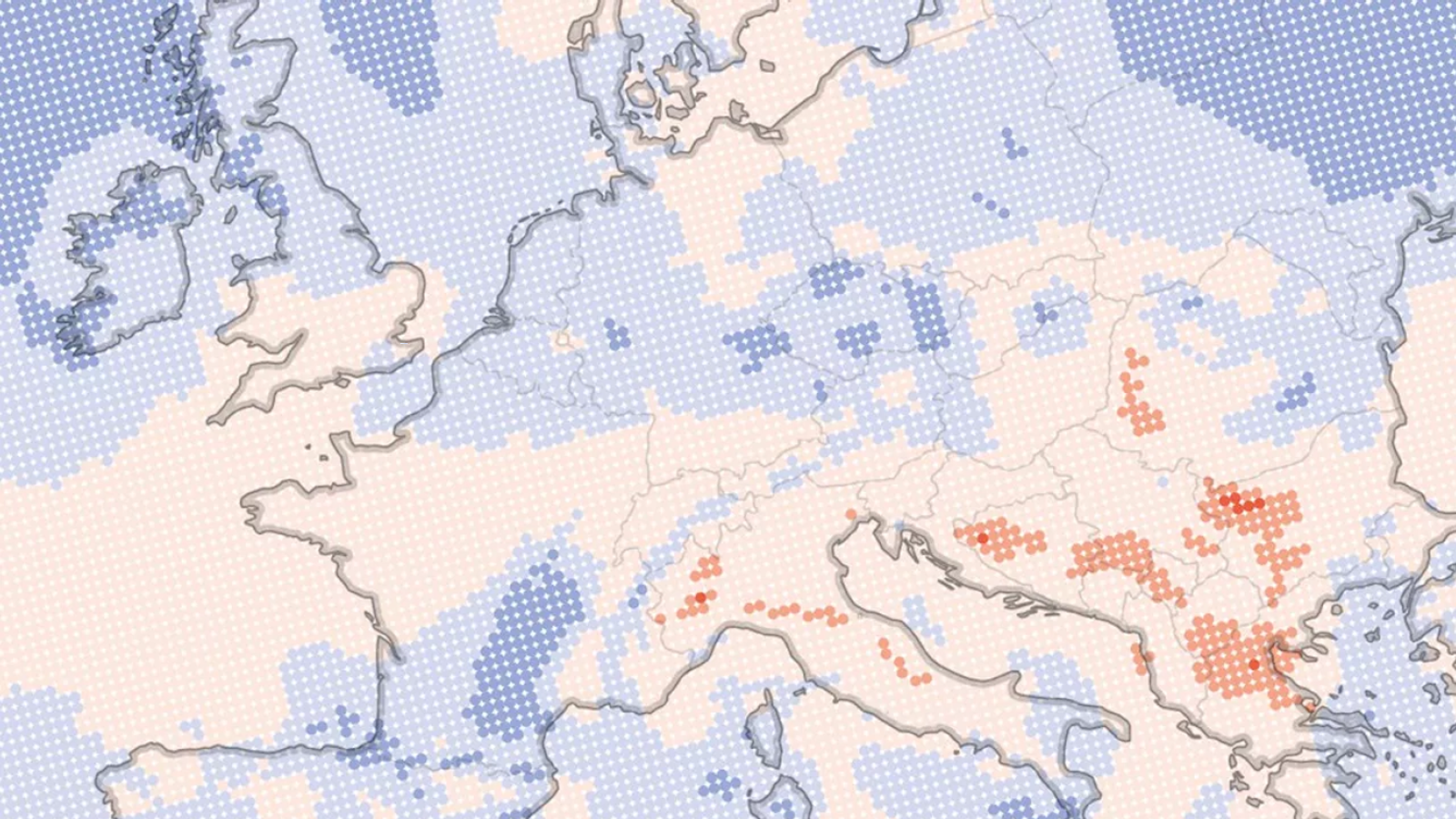

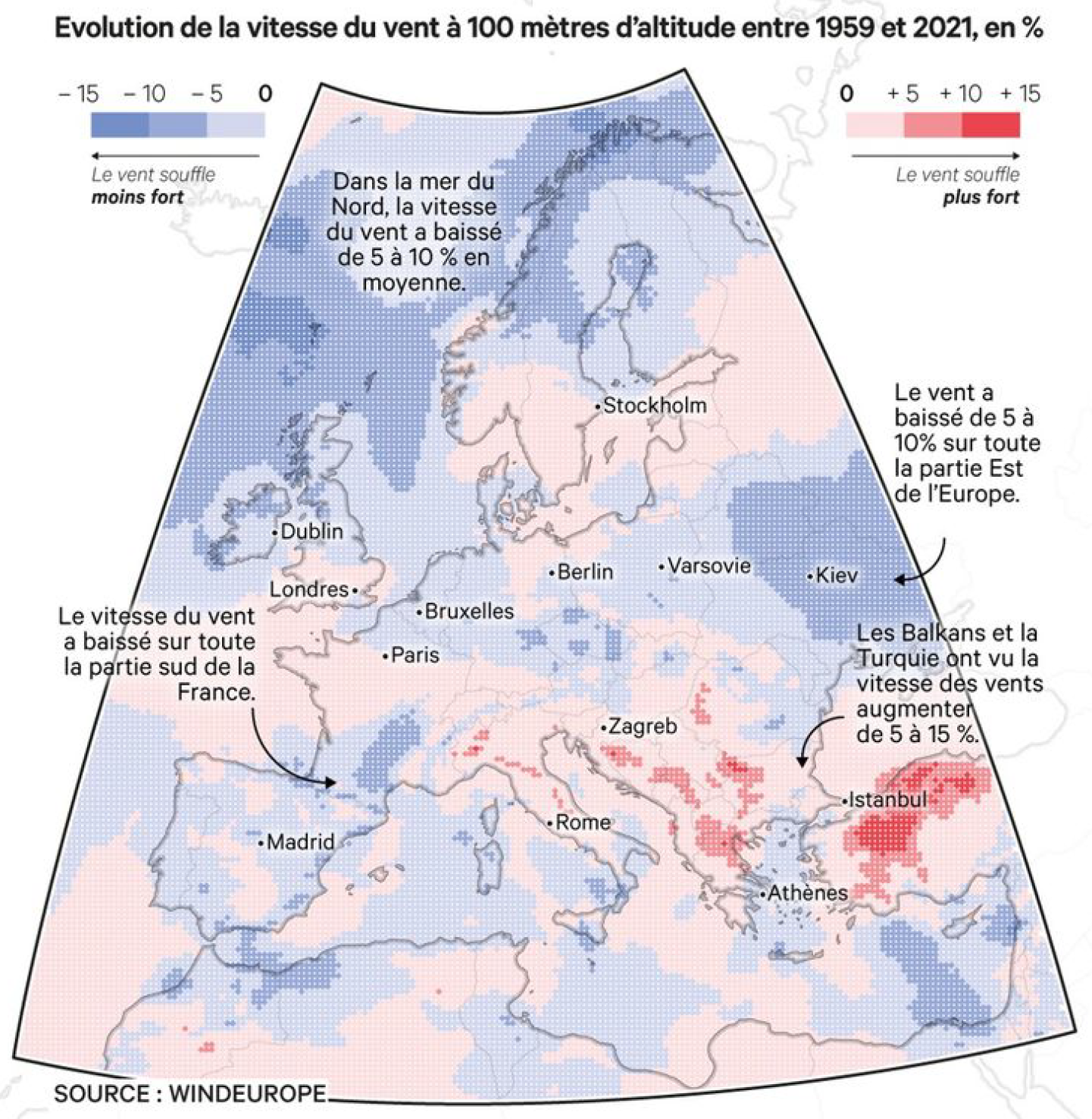

- And as this map shows, Europe has just suffered a “wind drought,” with more to come.

Energy-wise, Europe is between a rock and a hard place: it needs so much, yet has so little of its own. That’s why decarbonization is an opportunity as well as a challenge.

The first goal of eliminating coal, oil, and gas as the power sources that keep Europeans warm and working is to get rid of greenhouse gases to keep the planet from boiling over. And as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has underscored, another worthy goal is weaning Europe off its dependency on less-than-friendly foreign suppliers like Vladimir Putin and others whom you would normally cross the street to avoid, geopolitically speaking.

A strategic insight

It’s a strategic insight that arrived a little too late. Putin has used Russia’s energy supply into Europe as a weapon in his war on Ukraine. With the flow of Russian oil and gas now largely cut off and the EU vowing never again to rely on it, two things will happen.

First, in the short term, Europe will face what the Germans are calling a Bibber-Winter (“shivering winter”), while the least well-off Britons will have to choose between “heating and eating,” as the tabloids call it. Second, in the long term, Europe’s energy crisis will incentive an acceleration toward a zero-carbon future. Wind and solar energy feature heavily in most of those scenarios.

Renewable, but not constant

However, there is a problem with both: They may be renewable, but they are not constant. There are plenty of days when the sun doesn’t shine, and lots of times when the wind doesn’t blow. Leaving solar to one side, one may think that it matters little when the wind does or doesn’t blow, because it all averages out in the end. But that is what this map is here for — to demonstrate otherwise.

For not only is wind inconstant from place to place, it also changes significantly over time.

In blue, the map shows the areas of Europe where average wind speeds last year were lower than in the preceding reference period (1991-2020). The map, from the French newspaper Les Echos, shows areas of greater decline in darker blue, but also, in red, areas where average wind speeds in 2021 increased.

Some notable points:

- Dark blue covers large areas of the North Sea, northern Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe, where wind speeds decreased by 5% to 10%.

- The same goes for smaller zones in Ireland, southern France, and the German-Czech border.

- However, wind speeds have increased by 5% to 15% in the Balkans and Turkey.

A drop in wind speed can have a major impact on wind turbines, which operate in a “wind speed window” between 14 and 90 km/h (9 and 56 mph).

Gone is the wind

Last year, the load factor — that is, the ratio of actual output to the theoretical maximum — dropped by 13% in Germany and the UK and by 15% to 16% in Ireland and the Czech Republic, Les Echos reports.

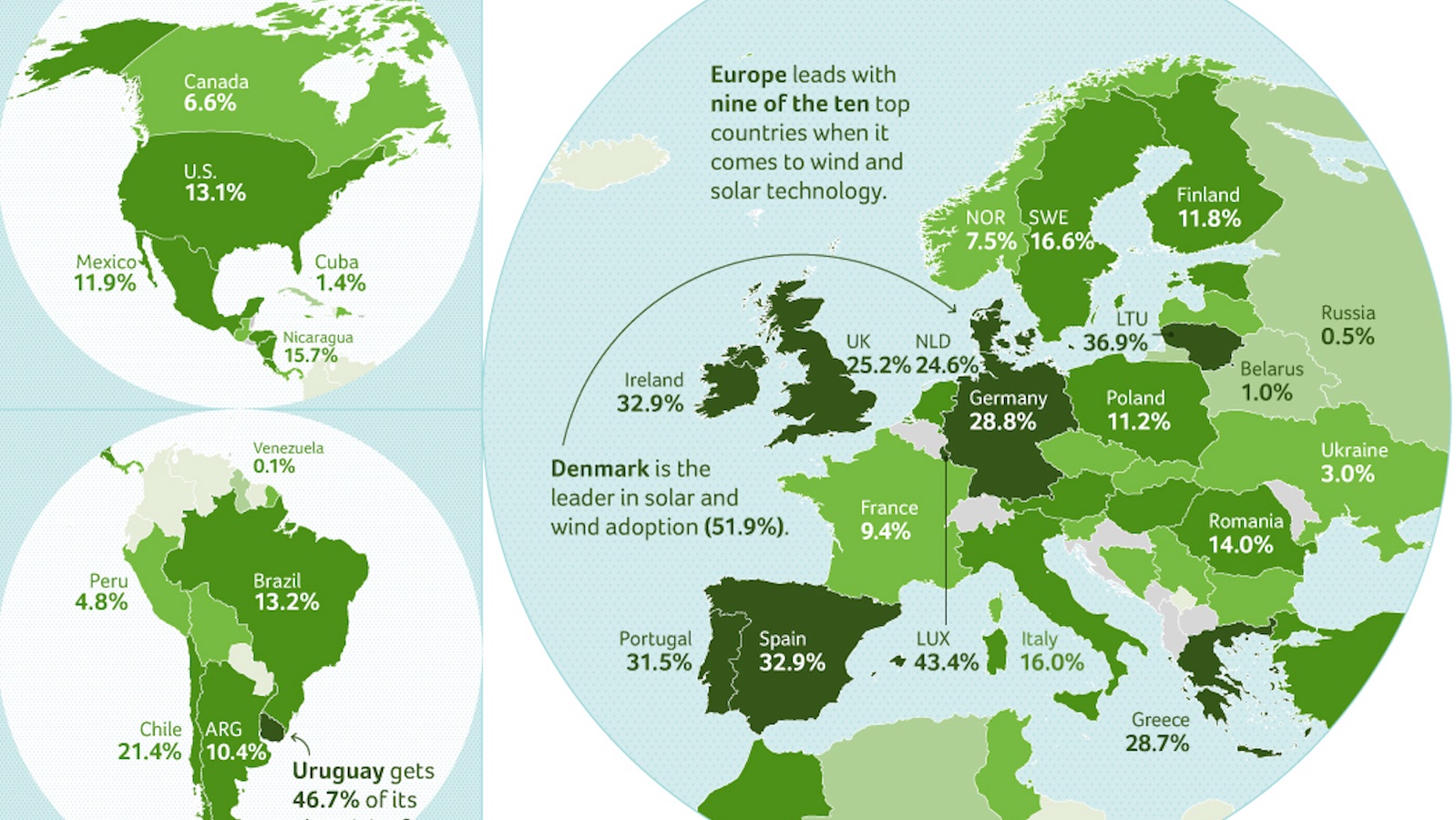

The 2021 “wind drought” hit Northern Europe particularly hard, especially those countries relying most on wind energy — notably Denmark, which gets 44% of its energy from wind, and Ireland, where the share of wind in total energy production is 31%. Other European countries relying heavily on wind include Portugal (26%), Spain (24%), Germany (23%), the UK (22%), and Sweden (19%). In France, which gets most of its power from nuclear, it’s just 8%.

As a result of the reduction in average wind speed, Danish energy company Ørsted reported a loss of €380 ($366) million. German energy company RWE acknowledged a 38% drop in profits last year, although this was from both its wind and solar units combined.

The coming wind drought

Unfortunately for Europe, it doesn’t seem that last year’s “wind drought” was a one-off. In its latest report, the IPCC predicts a drop of 6% to 8% in average wind speeds across Europe by 2050. As wind speeds become increasingly inconstant, the cost of wind energy will become more unpredictable and its provision more unreliable — that is, unless the energy industry invests in massive storage systems that can capture the excess energy produced on windier days and release it when the wind turbines stand idle.

It’s an issue that only will get more important as the share of wind in Europe’s total energy mix increases — which it will, due to the inexorable reduction in hydrocarbon-fueled power and the reluctance to fully embrace nuclear power.

Strange Maps #1172

Many thanks to Jules Grandin for the kind permission to reproduce his map from Les Echos (article here).

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.