Politicizing science is nothing new: it happened to Ben Franklin

And England almost burned themselves down as a result.

“When Benjamin Franklin inveted the lightning rod, the clergy, both in England and America, with enthusiastic support of George III, condemned it as an impious attempt to defeat the will of God.” –Bertrand Russell

In the 1700s, Earth was a pre-electric world. We didn’t have light bulbs, circuits or batteries. We didn’t know what electric currents or charges were. And many known phenomena — the aurorae, visible light, permanent magnets, static electricity, etc. — had their true nature obscured. In France, Charles Coulomb worked to discover the nature of electric charge and the forces between positive and negative charges. But in the Americas, it was Ben Franklin who made the greatest contributions, most famously through his discovery linking lightning with electricity. Yet politicizing his discovery led to disaster in England, and the historical politicizing continues to this day.

The alleged famed experiment was that Franklin flew a kite with a metal rod attached in a lightning storm, and some variation on that may actually be true. Lightning is the exchange of electrons from high up in the atmosphere with the Earth, which serves as a grounding source. It takes a tremendous build-up of electrons — somewhere around 10²⁰ of them — to create a single lightning strike. When the electric potential between the clouds and the ground is greater than the breakdown voltage in the air, a lightning strike occurs.

Franklin didn’t know much of this, but he did manage to understand the concept that electricity would follow the path of least resistance down to the ground, and that’s what led to the development of the lightning rod. Many metals conduct electricity better than other materials, and the closer you were to the cloud-tops, the more likely electricity would be to find you. The same reason you don’t seek shelter under the tallest trees in a lightning storm is the same principle behind why you don’t fly a kite with a lightning rod attached: lightning seeks the past of least resistance in getting to the ground.

That’s why Ben Franklin, when he developed the lightning rod, gave it two very distinct properties:

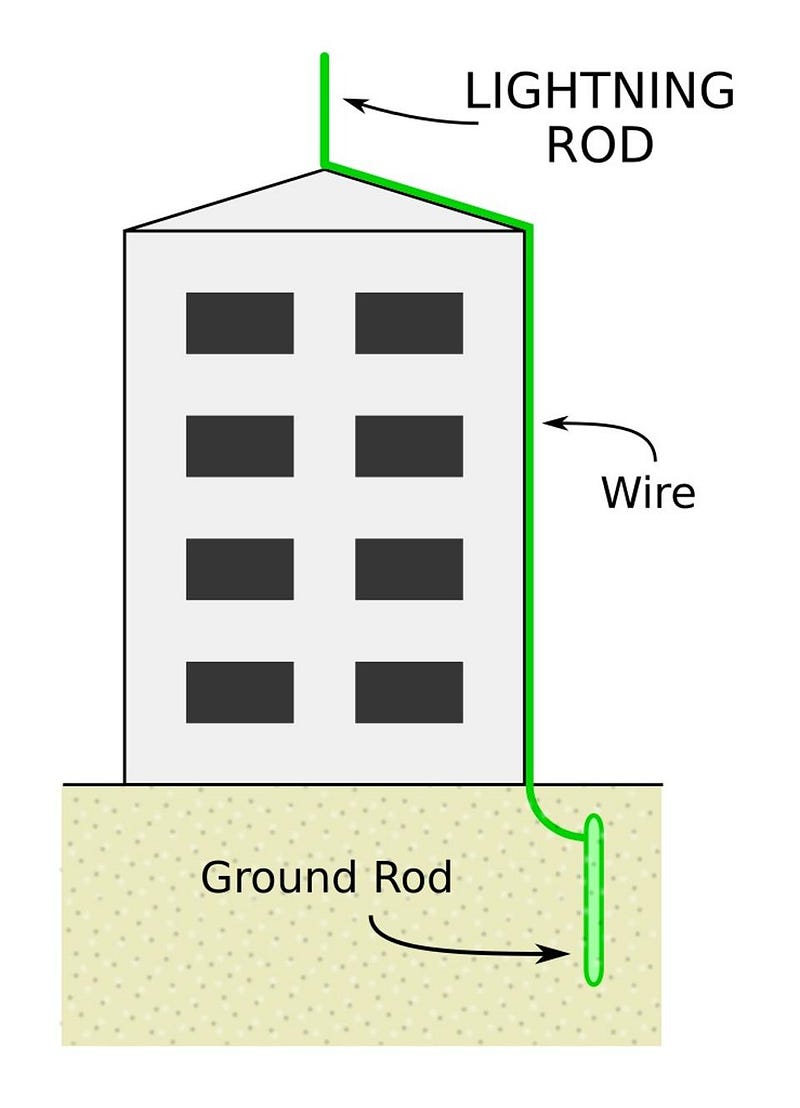

- It was a thick enough, sturdy enough and tall enough rod, connected to the ground by a wire, that it would be the highest point of the building it was attached to.

- And also, at the very tip, it would come to a point.

The first one is intuitive, once you understand that lightning is electricity. If lightning strikes your rod, you want it to flow entirely through the rod, into the ground, safely, without affecting the attached building or anyone inside. The Empire State Building, by far the tallest in its vicinity, gets struck by lightning more than 20 times each year, yet those strikes pose no threat.

But the “point effect” is more subtle. When there’s an electric field gradient, charges pool at the edge of a conductor. At a point, the charges reach a higher density than under any other conditions. More than perhaps two inches (5 cm) away from the tip of such a rod, the electric field around the top of the building becomes more dissipated. As a result, if there are many tall buildings around with lightning rods on them, lightning will be more likely to strike the ones without a pointed tip. The rod itself is more protection for a building if it does get struck by lightning, but the tip makes it less likely the building will be struck if there’s a better source around.

Franklin was a firm believer in sharing his knowledge and findings with the world, and news of the lightning rod spread across the Atlantic. But in England, King George III was no fan of the colonies, and was no fan of Ben Franklin in particular. British scientists came up with an alternative design for a lightning rod, with either a blunted tip or even a knob on the end, claiming superiority to Franklin’s model. To this very day, British lightning rods don’t come to a point, giving them not only a distinctly unique appearance, but meaning the physics of the rods is different as well.

Now, the story gets very interesting here, because the British and American historical accounts differ tremendously. Today, everyone agrees on the physics: that greater amounts of charge pool on a larger surface area, making it more likely that a rod with a knob will be struck than an equally high rod with a point. According to the stories told in England, their rods with knobs on the tips were more effective. They were better at rerouting lightning than Franklin’s rods; they made England safer than the Franklin design would have; they proved the superiority of British scientists.

But the American version paints a very different picture. Because electricity and the concepts of grounding and current flow were poorly understood, most lightning rods were built too thin, were insufficiently routed to the ground or, in some cases, were simply attached to the wooden roofs of buildings. Attach a thick, large-surface-area ball to that rod, and you’ve built a very successful lightning attractor, rather than a lightning diverter. Towards the end of the 1700s, many buildings in England indeed had their lightning rods struck by lightning, but they caught fire, burned down and left the next tallest building in the vicinity — also with an insufficiently grounded lightning attractor on it — next in line for the same fate.

It’s impossible to know, more than 200 years later, how much truth is in each version. We certainly understand lightning well enough today to know the advantages and disadvantages of each design, and can build and utilize either version quite safely. But it was anti-American (or an anti-Colonist) sentiment — along with King George III’s religious objections to this scientific application — in those days that led to the politicization of science in the first place. When you have an agenda, and a scientific claim stands in the way of that agenda, that’s when the politicization becomes a problem. It’s a problem with the tobacco industry; it’s a problem with the supplement/vitamin industry; it’s a problem with air and water pollutants; and it’s a problem with climate science. But hundreds of years ago, it was even a problem with lightning rods.

I like to imagine, somewhere, upon learning the news of British fires due to their lightning rod design, Ben Franklin was filled with delight. The United States of America wasn’t just founded by Washington, Jefferson and Madison, but by one of history’s greatest scientists of all. And yet one of his greatest strikes against the British Empire wasn’t intentional at all; it was a self-inflicted wound that grew of nationalism, foolish pride and a poor understanding of science. Let’s never make that same mistake again.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!