If we live in a capitalist world, why is it taboo to talk about money?

- American culture clearly considers the attainment of money to be a worthy goal, though talking about money is often considered taboo.

- One reason we struggle with talking about money may be that we have been taught to equate wealth with worth.

- Learning to have productive conservations about money can lead to better decision-making and less financial stress.

From weekly episodes of Keeping up with the Kardashians to the outrageously expensive costumes and jewelry displayed at the MET Gala, mainstream media is full of reminders that our culture mostly revolves around money and consumerism. But while we are taught from a young age that one of our primary goals in life is to amass as much wealth as possible, talking about our own income with other people is considered inappropriate.

Before we discuss how this blatant contradiction came into being, it’s important to recognize that the so-called “money taboo” is a bit more nuanced than we tend to give it credit for. As Joe Pinsker wrote in The Atlantic, it’s okay to ask somebody how much they spent on lunch, but not how much they set aside for their retirement. Both timeliness and size, it appears, help determine whether the purchase in question is suitable for conversation.

It doesn’t matter if that conversation takes place publicly or privately. A 2018 survey from Fidelity Investment Company found that in as many as 34% of cohabiting couples, one or both partners fail to accurately identify how much the other makes. Similarly, just 17% of parents with an income of $100,000 or higher tell their children how much money they have. Generally speaking, people feel more comfortable talking about extramarital affairs, addiction, and sex than money.

Understanding the money taboo

Such discomfort can have different causes. “Many Americans,” continues Pinsker, “do have trouble talking about money – but not all of them, not in all situations, and not for the same reasons. In this sense, the ‘money taboo’ is not one taboo but several, each tailored to a different social context.” When researching her book Uneasy Street: The Anxieties of Affluence, Rachel Sherman learned New York City’s ultrarich keep their income to themselves because they’re afraid of being perceived as privileged or corrupt.

Middle-class Americans also prefer to remain silent. Not because they’re ashamed of their modest wealth – quite the contrary – but because they don’t want to be perceived as desperate. As anthropologist Caitlin Zaloom writes in Indebted: How Families Make College Work at Any Cost, “protecting middle-class identity [means] silence about money” since “silence protects the idea that a middle-class family is independent and will be into the future, even if that’s not the case.”

Evolutionary explanations for the money taboo dig a little deeper. Back when our ancestors lived in tribal communities, our survival depended on our ability to work together. In this kind of environment, the last thing you wanted was to stand out from the crowd. Millenia later, neuroscientist Dr. Moran Cerf says in our interview, created in partnership with Million Stories, our brains still think this way. This explains why income – an “easy tool to quantify people’s position in a system” – is considered taboo.

Watch our full interview on money taboos:

Historical explanations are equally compelling. As political science professor Jeffrey Winters told Pinsker, societies with large wealth disparities are “inherently unstable.” Not only do they have to defend themselves from outside enemies, but they also must prevent infighting between the haves and the have-nots. In this context, taboos that prevent socioeconomic classes from openly discussing their variable incomes would have the added benefit of maintaining peace and stability.

Breaking the silence

Even if the money taboo benefits society at large in some perverse way, the same cannot be said for the individual. First and foremost, it is a source of stress, anxiety and interpersonal conflict. In an article written for Forbes, Laura Shin considers the case of a young professional from a lower-middle class family who was too nervous to ask about the average rent prices in a city they were moving to. Incapable of informing themselves, they ended up in an environment they could not afford to live in.

This person’s experience is not unique. A 2014 “Stress in America” survey conducted by the Harris Poll organization for the American Psychological Association found that 72% of respondents frequently worried about their finances. Of those respondents, 22% said that they experienced “extreme stress,” while 26% said they felt stressed “most or all of the time.” The money taboo might prevent these people from seeking the financial and emotional assistance they need.

If you are too embarrassed to talk about money with your therapist or significant other, you may want to consider some professional advice from the internet. As wealth psychology expert Kathleen Burns Kingsbury mentions in our aforementioned interview, most of us are under the impression that everyone else is better with money than us. That is, of course, untrue, and once you recognize that you will find that discussing income with others becomes a lot easier.

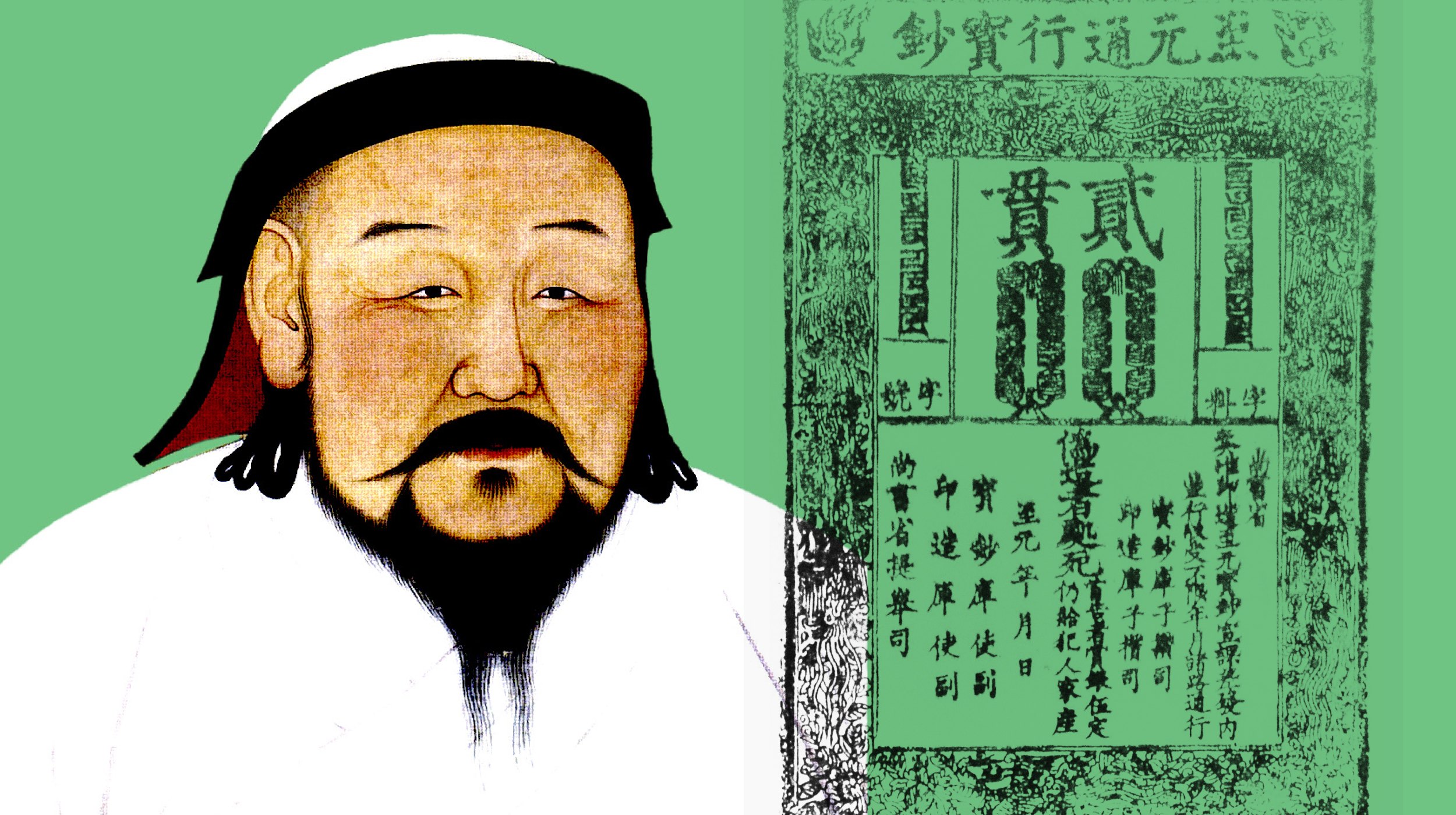

All too often, we struggle with talking about money because we have been taught to equate wealth with worth. This equation has become so deeply ingrained in the West that it is difficult to see the world in any other way. Other cultures may offer a way out. In China, anthropologist Kimberly Chong writes in Best Practice: Management Consulting and the Ethics of Financialization China, “personal worth is not primarily indexed to financial worth, but rather (…) moral and ethical values that cannot be reduced to economic value.”

In China, says Chong, employees freely discuss salaries. Not just amongst themselves, but also with their superiors. Such openness is not only valuable from a psychological standpoint, but an economic one too. American workers have a constitutional right to discuss wages, though this right has historically been suppressed by employers to keep the cost of labor down. By comparing wages, workers can find out if they are paid a competitive salary and how much they make compared to their co-workers.