The lasting anguish of moral injury

On a Sunday evening in September 1994, David Peters drove to a church service in Beckley, West Virginia, as the sun set over the horizon. He was 19 years old, just back from Marine Corps boot camp. He hadn’t been behind the wheel of a car all summer.

The road curved, and Peters misjudged the turn. Rays from the dipping sun blinded him. The car hit the median and headed straight at an oncoming motorcycle. And then, Peters says, “Everything went crash.”

His friend, sitting in the passenger seat, seemed fine. Peters got out of the car. The driver of the motorcycle was alive, but the woman who’d been riding behind him was now laid out on the pavement. Peters quickly realized she was dead.

Now an Episcopal priest in Pflugerville, Texas, outside Austin, Peters says there have been periods during the last 28 years when he’s found the knowledge that he killed someone almost unbearable. “I felt like I wasn’t good anymore,” he says. At times, he even wished he were dead. Years after the accident, he purchased a motorcycle, thinking “that’d be sort of justice if I died on a motorcycle.”

Peters may have experienced what some psychologists and researchers have begun to call “moral injury,” a concept introduced by a psychiatrist to describe the devastation he witnessed in Vietnam War veterans and others who believed they’d been ordered to act in ways that violated their personal moral code. The term encompasses a constellation of signs and symptoms that go beyond mere guilt and shame and can be so severe that people lose a sense of their own goodness and trustworthiness, leading to drastic impacts on daily functioning and quality of life.

Moral injury results from “the way that humans make meaning out of the violence that they have either experienced or that they have inflicted,” says Janet McIntosh, an anthropologist at Brandeis University who wrote about the psychic wounds resulting from how we use language when talking about war in the 2021 Annual Review of Anthropology.

Although research on moral injury began with the experiences of veterans and active-duty military, it has expanded in recent years to include civilians. The pandemic — with its heavy moral burdens on health care workers and its fraught decisions over gathering in groups, masking and vaccinating — intensified scientific interest in how widespread moral injury might be. “What’s innovative about moral injury is its recognition that our ethical foundations are essential to our sense of self, to our society, to others, to our professions,” says Daniel Rothenberg, who codirects the Center on the Future of War at Arizona State University.

Yet moral injury remains a concept under construction. It is not an official diagnosis in psychiatry’s authoritative guide, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). And until the recent publication of a major study on the subject, researchers and clinicians lacked well-defined criteria they could use to determine if someone has moral injury, says Brett Litz, a clinical psychologist at VA Boston Health Care System and Boston University. “The prevalence of moral injury is utterly unknown, because we haven’t had a gold standard measure of it,” he says.

‘It starts working on your head’

Moral injury was first described by Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist in Boston, who defined it as a sense of “betrayal of what’s right, by someone who holds legitimate authority (in the military — a leader), in a high-stakes situation.” In his 1994 book, Achilles in Vietnam, Shay quotes a soldier whose platoon fired on people at the beach one night, having been told by commanders that their targets were unloading weapons. But when daylight came, the soldiers realized they’d killed a bunch of fishermen and their children. “So it starts working on your head,” the soldier told Shay. “So you know in your heart it’s wrong, but at the time, here’s your superiors telling you that it was OK.” Incidents like this, Shay argued, are not just upsetting, but also damaging.

As the years passed, some researchers felt that Shay’s definition focused too narrowly on betrayal by leaders or country. In 2009, Litz and colleagues expanded the definition to include more personal types of moral injury, such as the lasting impact of “perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”

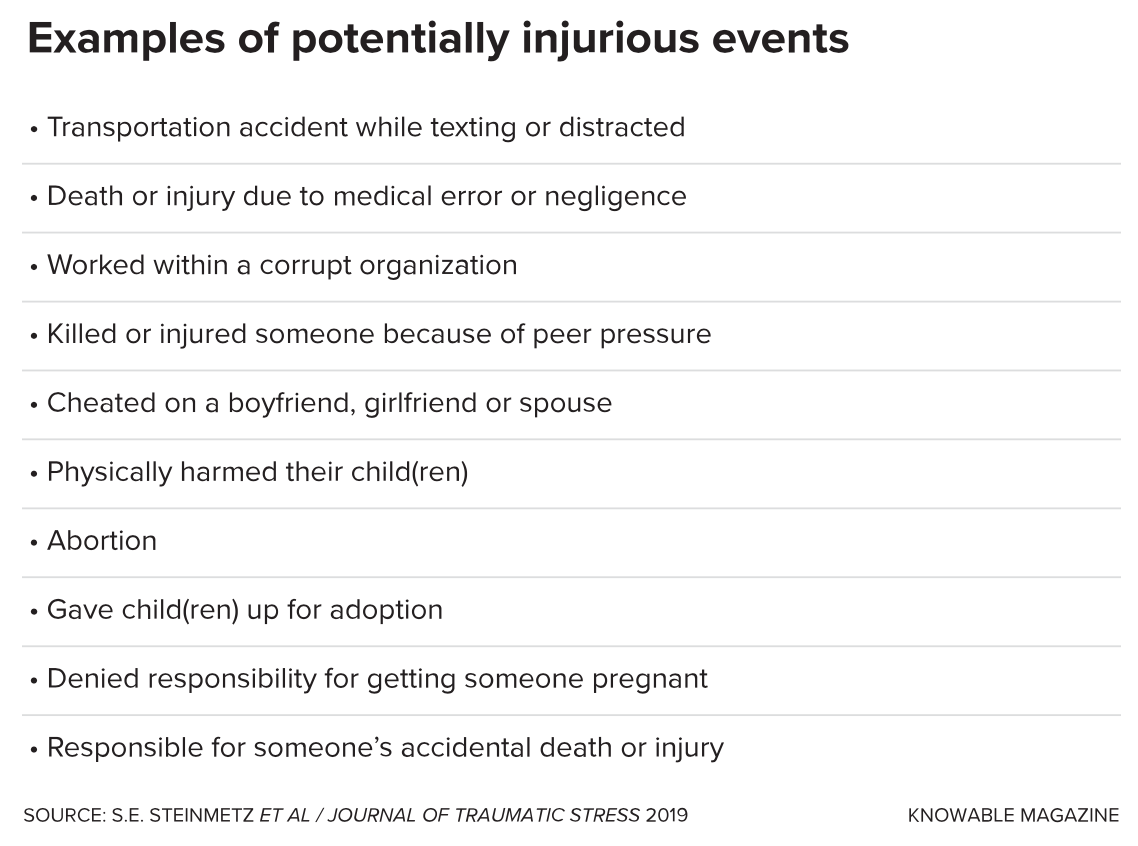

In a 2019 study, researchers devised a list of potentially morally injurious events to civilians by reviewing previous literature and research, as well as consulting experts and people who suffered from memories of morally distressing events. The researchers came up with 31 events that seemed to distress people enough to lead to moral injury, including a car accident while texting, sexual assault, working within a corrupt organization, witnessing abuse of power at work, cheating on a romantic partner and stopping providing for dependent children. But not everyone reacts to troubling events in the same way, and not everyone who experiences a particular event will suffer a moral injury, says study coauthor Matt Gray, a clinical psychologist at the University of Wyoming. What really makes a difference, he says, is “people’s moral framework and their appraisal of their actions or inactions.”

Because such actions and encounters can be traumatic, people with moral injury may appear to have post-traumatic stress disorder. But a diagnosis of PTSD does not capture the entirety of this kind of suffering, Shay and therapists who came after have found.

Many researchers view PTSD and moral injury as distinct conditions, although they overlap in their symptoms and the types of events that trigger them. PTSD is characterized by anxiety that develops after a serious physical threat of injury, sexual violence or death. But that triggering event doesn’t necessarily have to be morally injurious — it could be a natural disaster, say. For moral injury, on the other hand, the triggering event is always morally injurious but it may or may not involve a physical threat; it could be something like causing financial distress to others due to a gambling addiction.

Both conditions can involve intrusive memories of the traumatic event, avoidance of reminders of the event, lack of interest in pleasurable activities and detachment from others, Litz and colleagues wrote recently in Frontiers in Psychiatry (some researchers have categorized the overlapping symptoms differently). But moral injury is more likely to lead to other symptoms, Litz says, including alterations in self-perception, loss of meaning and loss of religious faith.

The two conditions may have different effects on the brain. In a 2016 study, active-duty military personnel seeking trauma treatment were asked to lie in a darkened room with their eyes closed for 30 minutes, after which they underwent a brain scan. Those who had been traumatized by a physical threat exhibited elevated resting neuronal activity in their right amygdala, a part of the brain associated with emotional responses, particularly fear. But those who were haunted by something they did or witnessed had more activity in their left precuneus, a part of the brain that is related to sense of self.

Over time, the moral injury research lens has expanded to include nonmilitary populations such as police officers, teachers, refugees and journalists. One 2019 study, for instance, surveyed teachers and other K-12 professionals in an urban Midwest school district, where some schools were white and affluent, some were racially and economically mixed, and others were largely made up of impoverished students of color. The less affluent and the more segregated the students, the more likely the teachers were to experience moral injury, writes the study’s author, Erin Sugrue, a social worker at Augsburg University in Minneapolis. “Professionals in these schools may experience moral injury as they come into close contact with the impact of racism and income inequality, two inherently immoral social forces, on the daily lives of their students.”

During the pandemic, researchers have turned their focus to the medical front lines. One recent study led by Jason Nieuwsma, a clinical psychologist at Duke University School of Medicine, analyzed data from a March 2021 survey of health care workers. They reported potentially morally injurious experiences that included hospital policies that prohibited dying patients from receiving visitors, watching some people refuse to wear masks to protect those who were more vulnerable, and being too overworked to provide optimal care. One wrote: “My line in the sand was treating patients in wheelchairs outside in the ambulance bay in the cold fall night. I got blankets and food for people outside with IV fluid running. I was ashamed of the care we were providing.”

Roughly half of the health care workers reported they were troubled by witnessing others’ immoral acts, and just under a fifth (18.2 percent) reported that they were troubled by having acted in ways that violated their own morals and values. “It begs the question of whether that experience will persist over time,” Nieuwsma says. “It’s something health care systems need to pay attention to.”

Still, Nieuwsma, who has largely studied moral injury in a military context, says he and other researchers have been reluctant to apply the term to the civilian population. “We want to preserve the intensity” of the description, he says.

To distinguish between normal moral stress and abnormal distress at levels that may require therapeutic intervention, Litz and Patricia Kerig, a clinical psychologist at the University of Utah, propose a moral continuum. At one end is the kind of moral frustration one might experience over an upcoming local or national election, events that are not immediately personal. Then there are more distressing events involving a personal, moral transgression (like if you behave hurtfully to someone you love or steal someone else’s idea). A person may lose sleep over such issues, but they are not disabling and do not define the person in question. At the far end of the spectrum is the type of debilitating moral injury that consumes a person with intense guilt or shame.

But what exactly are the parameters of that injury? So far researchers and clinicians have lacked an objective measure of moral injury. To rectify that, Litz and 10 colleagues, along with a broad consortium of other experts, recently sent questionnaires to hundreds of active-duty service members and military veterans in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and Israel who had suffered potentially morally injurious experiences. From their responses, the researchers identified 14 reactions that indicate the presence of moral injury. The list includes statements like “I have lost pride in myself” and “I am disgusted by what happened.” The researchers believe their new “moral injury outcome scale,” will be a useful tool for future studies.

Forward-looking therapy

Nearly 30 years ago, Shay saw that a diagnosis of PTSD didn’t encompass all that Vietnam veterans were dealing with. And today, psychologists recognize that the treatments don’t directly translate, either. Treatment for PTSD typically involves drugs that treat depression and anxiety, as well as therapy intended to help patients reframe negative thoughts about the trauma and gain control by facing negative feelings. With PTSD, “we’re trying to reappraise and reinterpret and recontextualize that event, and we’re trying to get you, in the here and now, not to be as reactive to it,” says Gray. In a sense, such therapy is “backwards-acting,” he says.

For someone struggling with moral injury, however, it may not be possible to recontextualize the inciting event, because in some cases it’s truly what it appears to be: a violation of a person’s moral code. As a result, Gray says, therapy for moral injury needs to be forward-looking, or what he, Litz and colleagues describe in a 2017 book as “adaptive disclosure.”

This form of therapy attempts to help the patient come to terms with their moral injury by shifting their perspective. A patient may blame themselves or others for what went wrong, and this may be objectively true, the authors write. But in therapy, the patient can be encouraged to take ownership of the act; consider forgiving themselves; commit to actions that have real or symbolic reparative value (such as someone who harmed another by driving while drunk agreeing to speak to high school students about the dangers of mixing driving and alcohol consumption); and recognizing that condemning themselves for the horrific act cannot erase it, but can prevent them from doing good in the world going forward. It essentially tells the person, “You have things that you can still contribute, and that ultimately will be more productive and more meaningful than just isolation and self-loathing,” Gray says.

If this sounds a lot like traditional religious teachings, that’s not far off, says Harold G. Koenig, a psychiatrist at Duke University School of Medicine. “This is something that religions have dealt with, and continue to deal with, since the beginning of time,” he says. Koenig and colleagues have been developing what he calls “spiritually integrated” therapies for moral injury based on the scriptures of the world’s major religious traditions, as well as interventions designed specifically for chaplains to help them treat people of any faith or even those without a faith.

One example of the latter intervention is called “pastoral narrative disclosure.” It’s based on the idea that confession and absolution are key to redemption. As described in a 2018 paper, it involves helping the patient reflect on what happened, attempting to place it within the context of the person’s entire life, and then creating an absolution ritual that has spiritual meaning for the patient.

As for Peters, he’s connected with a support group of people who have accidentally killed someone, and he’s writing a book to help others in his position. He’s also taken comfort in the concept of a city of refuge, described in the Old Testament as a place for accidental murderers to stay safe from possible avengers. “I had to build a city of refuge for myself,” Peters says.

His “city” includes art, theology, the comfort derived from the community he found online and a mission to reduce dependence on cars. It’s a place, he says, “where I am able to live, but also live with the awareness that I’ve done this thing.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.