Your personality is linked to risk of dementia and cognitive decline

- Our personalities shape our behavior and thought patterns, influencing our physical and mental health. But do some personality traits influence the progression toward or away from dementia?

- A 2022 study found that conscientiousness protects against moderate cognitive impairment, whereas neurotic people experienced more years of cognitive decline.

- The findings provide a novel understanding of how personality traits can hasten or slow the transitions between cognitive statuses and death.

Picture two individuals. The first is highly organized, with excellent self-discipline and an extensive collection of Post-it Notes. The second is a bit more frazzled, worried, and emotionally unstable. Now, let’s turn time forward to view our subjects in their upper 70s. If you had to guess, which person do you think might be suffering from cognitive decline — maybe even dementia?

It turns out that a lifetime of being organized and productive might protect the brain. In situations of high stress and anxiety, the brain might be working harder. Experienced consistently across an average lifespan, that condition can damage the brain.

These two sets of behavior reflect one of many personality differences that researchers know can add up to influence health outcomes.

A 2022 study from the American Psychological Association, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, suggests that certain personality traits also affect the cognitive decline of older adults. Led by author Tomiko Yoneda from the University of Victoria, the researchers found that individuals with high conscientiousness were much less likely to develop dementia. Further, they had more capacity to recover from moderate impairment. Neurotic individuals — people more prone to stress and worry — were more likely to plunge into cognitive decline, and to stay there.

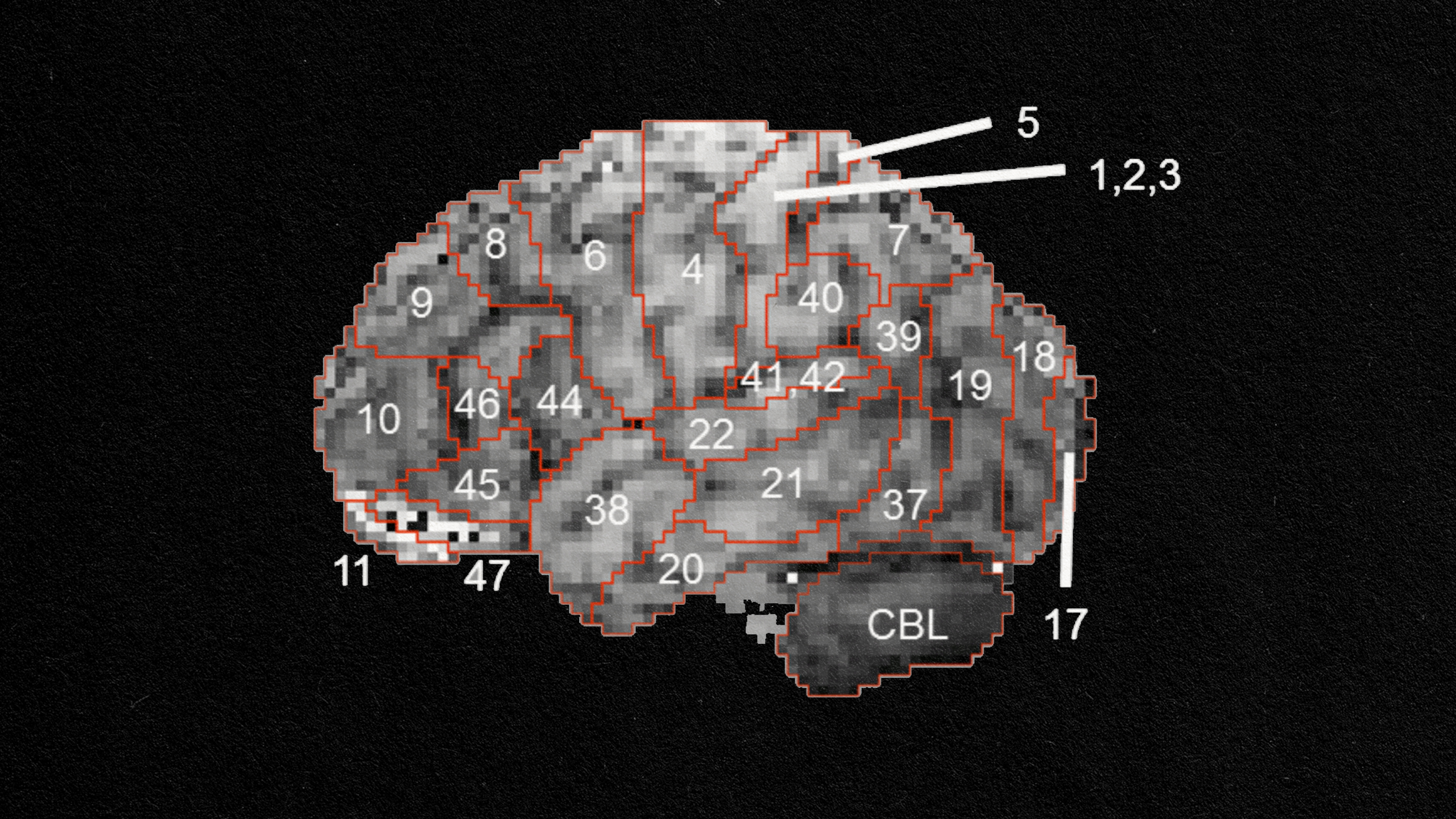

The researchers leveraged data from nearly two decades of annual assessments taken on nearly 2,000 older adults to estimate the association between personality traits and the risk of cognitive decline. This model structure allowed the researchers to assess the entire pathway of cognitive impairment. It provided new insights on how the progression of each stage influences the other, and how personality might play a role in regulating all of it.

The role of personality

Your personality acts as an internal compass. Throughout your life, it guides you toward or away from certain behaviors and thought patterns — factors that over a lifetime might harm or benefit your health, resilience to disease, and longevity.

A common way to assess personality is to rank an individual according to the Big Five personality traits: extroversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. Because we all have personality — and a vested interest to live — we all want to know how personality traits affect the quality and span of our lives. The question has implications for policymakers, doctors, and researchers who work in public health.

The association between personality and lifespan has gotten a lot of attention, resulting in a broad understanding that personality does matter. For example, conscientious individuals, who tend to be highly organized and self-disciplined, are less likely to engage in violence and drug use. They are also more likely to have a healthy diet and to exercise well. On the other hand, neurotic individuals, who may be naturally prone to anxiety and stress, are likelier to turn to short-term relief involving drugs, alcohol, or even violence. Plus, chronic stress is associated with lower brain volume and other biological markers of cognitive decline.

Building a model

To examine the association between personality traits and cognitive health, researchers analyzed data from 1,954 participants in the Rush Memory Aging Program. This program tracks and studies the mental and physical health of older adults (average age of 80) living in the greater Chicago region. It began in 1997, when participants without a dementia diagnosis were recruited from senior housing facilities, church groups, and other organizations.

As part of the program, the participants received one personality assessment through the NEO Five Factor Inventory. Each trait is scored, with a higher score indicating higher levels of each trait. A composite score between 0 and 48 rated traits like neuroticism and conscientiousness. Scores from 0 to 24 measured extraversion, the trait that defines how much an individual enjoys and seeks out social engagement. Participants also receive annual assessments across a variety of biological and neurophysiological variables. In exams of cognitive impairment, each individual is diagnosed as having either no cognitive impairment, mild to moderate cognitive impairment, or dementia.

For their study assessing personality traits and cognitive impairment, the researchers also considered covariates like sex; education; and history of illnesses such as heart disease, stroke, vascular disease, and depressive symptoms. Females comprised the vast majority of participants (74 percent).

The authors thought of impairment as a three-staged process. It proceeds from normal health toward moderate decline and eventually ends in dementia. They fit this information into a statistical model called multistate survival modeling, which discriminates between the effects of factors at different stages of impairment and allows for an individual to move forward and backward between stages. For example, the researchers were especially interested in the transition from normal brain health to moderate decline, and the potential recovery away from cognitive impairment back to normal health.

Out of the five key personality traits, they studied conscientiousness, neuroticism, and extraversion. They asked whether any of these traits were associated with progression toward dementia, and away from it.

It pays to be organized

The results of the models were unequivocal: Individuals who scored higher on measures of conscientiousness had a decreased risk of cognitive impairment, whereas subjects that scored higher in neuroticism suffered the opposite fate. The latter were more likely to move forward through the stages of cognitive impairment.

Extraversion scores had a more complex association with cognitive decline. According to the model, the most extroverted individuals received no special protection against cognitive impairment. However, once these individuals developed moderate levels of impairment, they were more likely to recover, suggesting that higher extroversion might cause these individuals to seek out help. Once dementia sets in, these benefits are already exhausted.

Overall, women were less likely to experience cognitive decline than men, and higher education was associated with a decreased risk of cognitive impairment. None of the personality traits were associated with life expectancy.

Personality can only do so much

Most of the significant associations that the researchers found concerned the initial onset of cognitive impairment. The transition toward dementia and death was not associated with any specific personality trait.

When taken as a whole, these results demonstrate that people developing minor or moderate cognitive impairment have a chance to reverse the process, and that personality might tip the scales toward recovery or further impairment. However, once dementia sets in, the effects of personality fade. In fact, of the 1,954 individuals studied, only 114 went from dementia to moderate impairment, and only 12 recovered fully. On the other hand, 725 individuals, or 37 percent percent of the study’s participants, returned to exhibiting no discernable levels of cognitive impairment after being diagnosed with minor to moderate issues.

A compelling story

The researchers were not able to assess how the other two traits in the Big Five (agreeableness and openness to experience) affect cognitive decline, though we know both traits are associated with improved health. The data also came from a very educated, very female, and very white population.

Introducing measures of openness and agreeableness on a more diverse dataset would improve the generalizability of the study and broaden our understanding of how personality traits affect the transitions between cognitive statuses and death. Additionally, the researchers pointed out that personality might change in older adults, especially those whose brains are experiencing physical changes. According to the researchers, “although personality traits are relatively stable after 30, more substantial personality change may occur during the progression to dementia.”

Still, the robust method and large sample size paint a compelling story — a story backed by hundreds of papers studying the influence of personality. If you want to live a long, healthy life, it helps to be more diligent, organized, productive, and calm. It might even help you more than eating your broccoli.