You can live just fine with half a brain

- Until recently, it was widely believed that the adult brain is fixed and cannot repair itself. But in fact, it is very dynamic.

- The brain does continue to change throughout life, but its capacity for change is greatest during childhood. A child who loses one hemisphere of their brain can actually retain its functions.

- Children who have a brain hemisphere removed behave completely normally. But exactly how the brain reorganizes after large portions of it are removed is still unclear.

Senator-elect John Fetterman (D-PA) suffered a stroke in May this year, but he eased back onto the campaign trail within just a couple of months. Fetterman’s recovery showed in real-time how the brain can reorganize itself to work around insult and injury.

As recently as the 1990s, it was widely believed that the adult brain is fixed and cannot repair itself. In fact, it is highly dynamic, and it alters its structure and function in response to just about everything it experiences. The mechanisms responsible for these changes are collectively referred to as neuroplasticity.

Malleable matter

While the brain does continue to change throughout life, its capacity for change is greatest during childhood and decreases with age. For example, Helen Santoro was born without a left temporal lobe, a brain structure that is crucial for language, but she has a passion for language and works as an investigative journalist. If an adult were to have their left temporal lobe removed, they would almost certainly lose their language abilities for good. As we see in stroke patients, even minor damage to the structure can significantly impact speech. It can take years for a patient to recover from more severe damage.

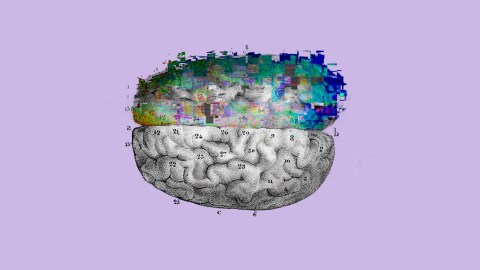

New research provides more evidence of just how malleable the brain is early in life. A study published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that both hemispheres are capable of taking over the functions of the other when one of them is removed in childhood.

Michael Granovetter of the University of Pittsburgh and his colleagues examined 40 people who had the left or right hemisphere of their brain removed in childhood. The removals came mostly as a last-resort treatment for debilitating, drug-resistant epilepsy.

The researchers tested the subjects’ ability to recognize words and faces — functions which in most people are lateralized to the left and right hemispheres, respectively. They presented the subjects with pairs of words and faces in quick succession and asked them to indicate whether each were the same or different.

The participants performed this task with about 80 percent accuracy, falling only slightly short of the accuracy of 31 age- and sex-matched controls. Crucially, it made no difference which hemisphere had been removed: Those missing their left hemisphere recognized words as accurately as those missing the right, and those missing the right hemisphere recognized faces just as accurately as those missing the left.

“These results demonstrate the remarkable plasticity of the developing brain,” tweeted Granovetter. “A single developing left or right hemisphere is ultimately able to largely support the functions that adults require both hemispheres for.”

The brains of left-handers

Children who have a brain hemisphere removed — a procedure known as hemispherectomy — behave completely normally, but exactly how the brain reorganizes after large portions of it are removed is still unclear.

One recent brain imaging study points to large-scale reorganization of the remaining hemisphere, with different regions competing to perform functions that had been the province of the missing hemisphere. Another shows an individual born without the left temporal lobe who has a fully functional language network in the right hemisphere.

A bigger question is how and why certain brain functions are lateralized to the left or right hemisphere in the first place. Lateralization is closely related to handedness, or the tendency to use one hand rather than the other.

Nine out of 10 people are right-handed, and while left-handers have been historically disadvantaged, being left-handed confers some advantages. Some left-handed people appear to have speech functions in both brain hemispheres, and they are thus likely to fare better than right-handed people after a stroke.