If you don’t like your personality, you can change it

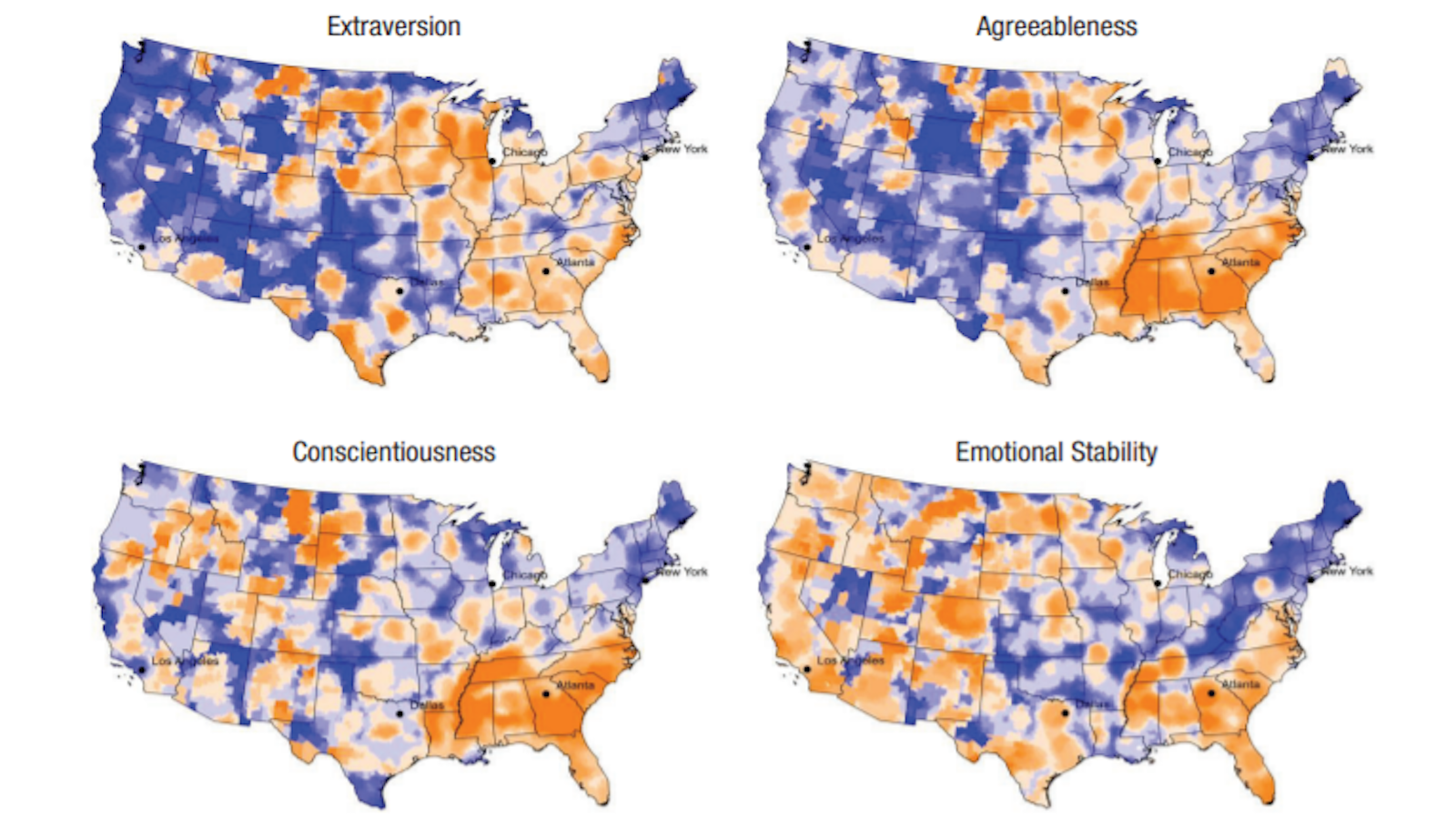

- The Big Five personality traits are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

- These traits predict all manner of life outcomes, from salary to marital happiness to political affiliation.

- But personality is not necessarily permanent. If you want to change your personality, you can “fake it till you make it.”

Your personality predicts how happy your marriage is, how much professional success you have, and when you will die. These predictions aren’t based on one or two small studies of a few people or a few outcomes. Hundreds of studies across multiple countries involving hundreds of thousands of people find that personality reliably predicts important life experiences and outcomes ranging from religious beliefs to depression to political affiliation.

Moreover, these effects are not tiny: personality predicts major life outcomes like wages, arrest rates, and physical health about as much as cognitive ability and socioeconomic status do. Sometimes, personality is even more important. For example, several studies find that personality can be a better predictor than IQ for employment, mental health, and voting participation. And personality accounts for over 30% of variance in marital satisfaction.

How do you measure personality?

Personality’s importance might surprise you if personality tests make you think of online quizzes (like what Harry Potter character you are or what your favorite animal says about you). Not surprisingly, these tests are more about fun than science. (Even commonly used formal personality tests like the Myers-Briggs inventory are psychometrically limited and lack the validity needed to reliably predict outcomes.)

But the “Big Five” personality traits stand apart. Though numerous models and assessments have been developed over the last 100 years, the Big Five are the most prominent and well-researched. Instead of categorizing people, it measures how people fall along a continuum from low to high for each trait. Importantly, these are the traits that predict all those outcomes mentioned above. The Big Five traits spell out the acronym, OCEAN:

- Openness refers to openness to new ideas and experiences. Highly open people tend to enjoy imagination and art, feel a depth of emotion, enjoy variety, be adventurous and intellectually curious, and be comfortable challenging authority and tradition. Your friend who loves modern art and once spent a summer backpacking abroad is probably high in openness.

- Conscientiousness is a measure of oderliness and industriousness. Highly conscientiousness people tend to be dutiful, goal-driven, self-disciplined, and deliberative. A conscientious person is always on time and never makes an impulsive decision.

- Extraversion refers to sociality, animation, and energy.Highly extraverted people tend to be talkative and outgoing and thrive in a stimulating external environment. This is your assertive friend who loves excitement and meeting new people.

- Agreeableness is a measure ofcooperation and social harmony. Highly agreeable people tend to be empathetic, trusting, warm, and considerate. This is your friend who is always nice to everyone and hates confrontation.

- Neuroticism refers to anxiety and emotional volatility. Highly neurotic people tend to be easily stressed and may frequently experience negative emotions like fear, anger, guilt, and frustration. This is your friend who gets easily worried and has occasional mood swings.

These traits were identified using a statistical technique called factor analysis to assess how common language describes people’s personalities. Essentially, each trait tends to correlate with certain words that overlap little with the other factors. For instance, someone who is highly extraverted is likely to be described as outgoing or social and unlikely to be described as quiet or reclusive. But their level of extraversion is unlikely to relate much to their level of openness or neuroticism.

Of course, these five personality traits do not account for all behavioral variation — environment, social background, and cognitive ability matter. And some academics argue for the addition of other traits (e.g., honesty-humility). But the beauty of the Big Five is that it distills an overwhelming number of traits into a manageable subset that reliably predicts numerous life outcomes. If you are curious, several reasonable Big Five tests are available online.

Oh no! I’m a boring, disorganized hermit who is mean and always upset

You’re not alone. Surveys estimate that around 70% of people want to change at least one personality trait. But there is reason for optimism.

First, you might not be a boring disorganized hermit who is mean and always upset. Instead, you may be a traditional, laid-back reflective person who is straightforward and just somewhat anxious. The Big Five traits do not have inherent positive or negative value. Though each trait predicts certain life outcomes (e.g., conscientiousness predicts career success and longevity, while neuroticism predicts depression), the traits are neither good nor bad.

For example, highly extraverted people may be stronger leaders, but introverts (who score low on extraversion) may be better listeners who process information more carefully. Highly agreeable people may be better at conflict resolution, but less agreeable people may be more effective at negotiating sales. Even neuroticism — perhaps the most maligned of the traits — appears to boost performance on effort-based tasks and to spur vigilance and healthy behaviors in some circumstances.

Need a personality change?

Second, you can change your personality. Until recently, I would have told you to resign yourself to a life with your fate-given personality. One of the defining characteristics of the Big Five, after all, is that they are traits rather than states — meaning that, barring brain disease, brain trauma (a la Phineas Gage), or some major life event, by adulthood your personality is stable across circumstances and lifespan. Indeed, even though people tend to become slightly more agreeable and less neurotic with age, their rank-order compared to other people is surprisingly consistent.

But over the last few years, researchers have begun finding evidence that personality is not completely out of our control. Instead, people may be able to intentionally change their personality traits. Spurred by work by Marie Hennecke and colleagues, models of personality change generally distinguish between latent personality traits and behavior at a particular time (i.e., states). For example, someone might be low on conscientiousness generally (trait) but on-time and prepared for a specific meeting (state). If, however, someone makes a concerted effort to repeatedly change their state, over time this can change their trait.

In some ways this may seem obvious: your personality is, after all, a label describing how you tend to think and behave. Change how you think and behave, and your personally does too. Just “fake it till you make it.”

Crucially, though, personality change takes more than just desire or occasional behavior change. It demands that people intentionally change their thoughts, strivings, and behavior over time — so much and so often that the new way of thinking and behaving become a habit that extends to other life domains. If someone wants to become more extraverted, for example, they might need to force themselves to participate in and positively reflect on numerous social situations over many months before truly beginning to look forward to them.

The good news is that even though volitional personality change is effortful, you may enjoy the process more than you expect. Introverts, for example, underpredict how much they will enjoy acting extraverted. And successful personality change is likely to increase your well-being and may improve other life outcomes, like career success.