Even worms make complex decisions

- It is difficult to study complex decision-making in vertebrates due to their high-level neural network.

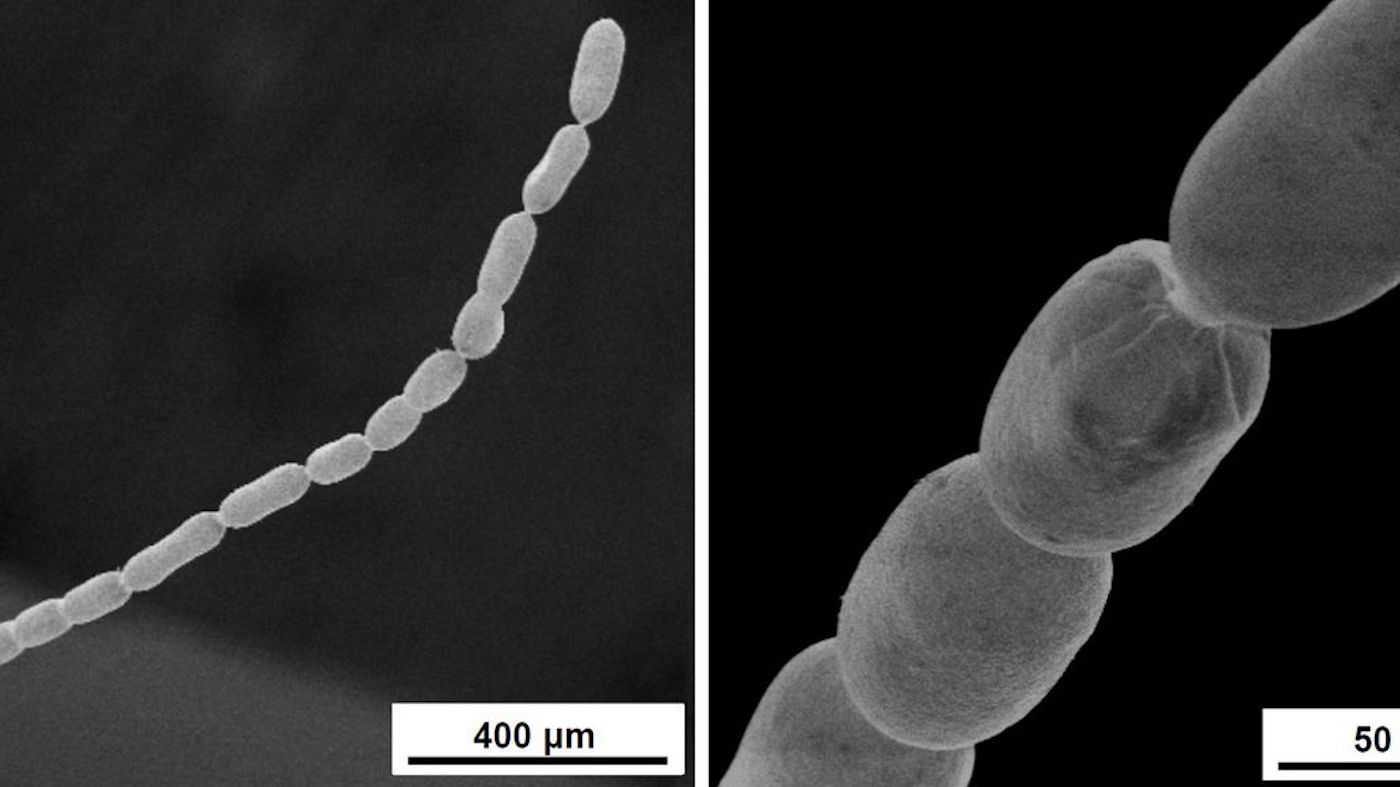

- Researchers at the Salk Institute showed that a worm, Pristionchus pacificus, is capable of complex decision-making.

- P. pacificus weighs costs and benefits to determine if it should eat bacteria or bite other worms.

With my face squished against the bakery’s window, I must make a decision: bran muffin or triple-chocolate éclair with whipped cream dipping sauce. On one hand, the decadent pastry is more expensive and less healthy. On the other hand, it’s prettier and I’m stressed. Fortunately for me, I have about 86 billion neurons to work on this complex decision. Unfortunately for behavioral scientists, it is challenging to understand how complex decisions are made when 86 billion neurons are involved.

A group of researchers at the Salk Institute used a simpler approach to study decision-making. They used a worm with only 302 neurons, Pristionchus pacificus. Historically, scientists thought such a small neural network meant the worm only engaged in simple decision-making: I encounter food, so I decide to eat food. But the Salk researchers challenged that assumption and showed that worms are capable of complex decision-making — that is to say, worms conduct a cost-benefit analysis.

Pristionchus pacificus: Simple biter or complex decision-maker?

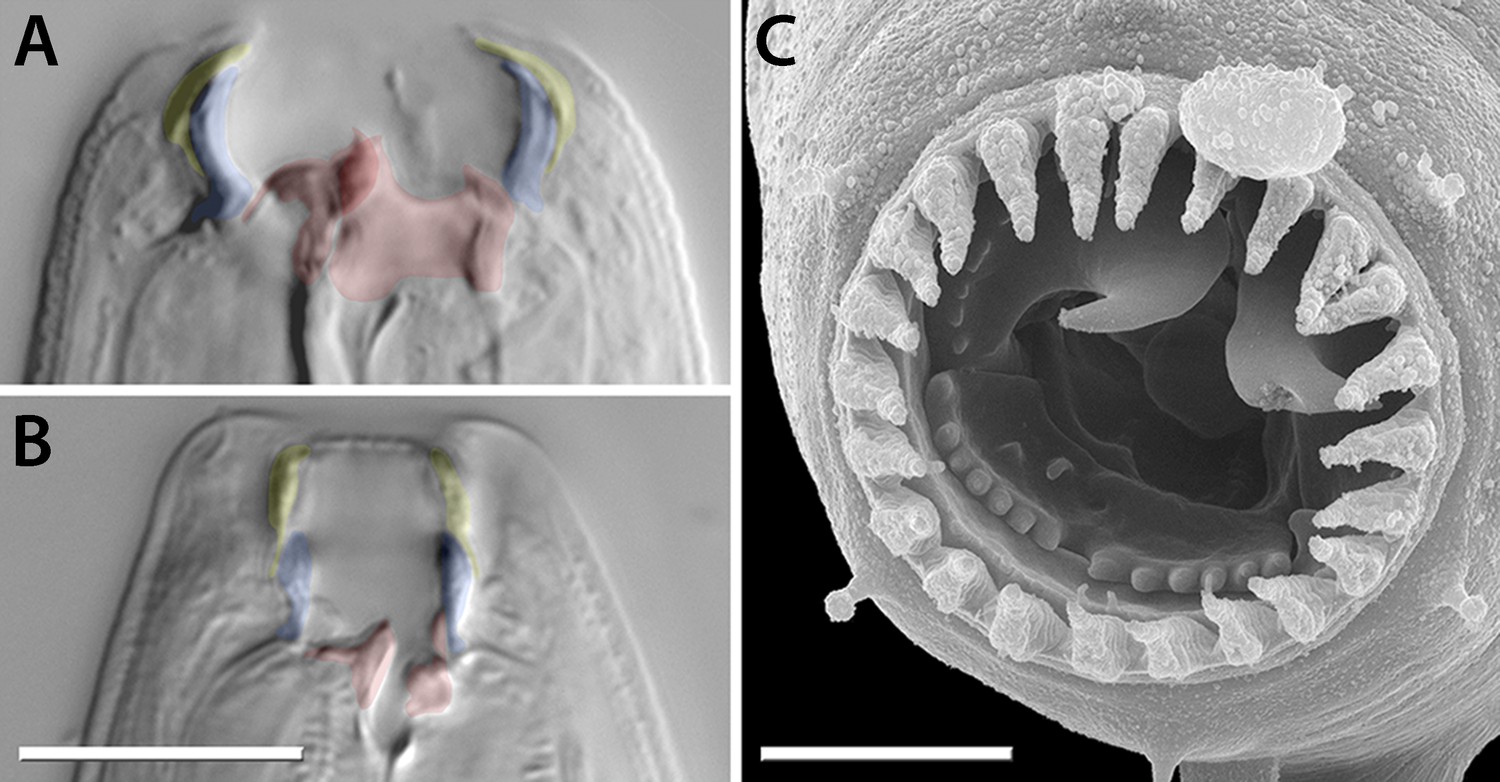

P. pacificus can be a vicious little nematode. It is armed with a ring of teeth, which it uses to bite other nematodes, such as Caenorhabditis elegans. Both organisms prefer the same food source, bacteria. Additionally, P. pacificus eats C. elegans. The predatorial worm typically kills larval C. elegans with a single bite, but adult C. elegans are tougher and easily escape. Historically, these non-fatal adult-targeted bites were considered failed predatory attempts. That is, the 302-neuroned P. pacificus simply tries to eat any C. elegans it encounters but is often unsuccessful. The researchers at Salk Institute, however, noticed something that caused them to question that assumption.

After being bitten, C. elegans avoid P. pacificus for about 10 minutes, retreating into areas with less food. This got the researchers thinking that maybe these bites weren’t just failed attempts for a meal. Perhaps P. pacificus had another goal in mind: territorial defense. The researchers hypothesized that P. pacificus weighed the costs of biting to the benefits of multiple outcomes (killing for food and defending territory). This type of complex decision-making behavior is familiar in vertebrates but unexpected in a worm.

To bite or not to bite: A cost-benefit analysis

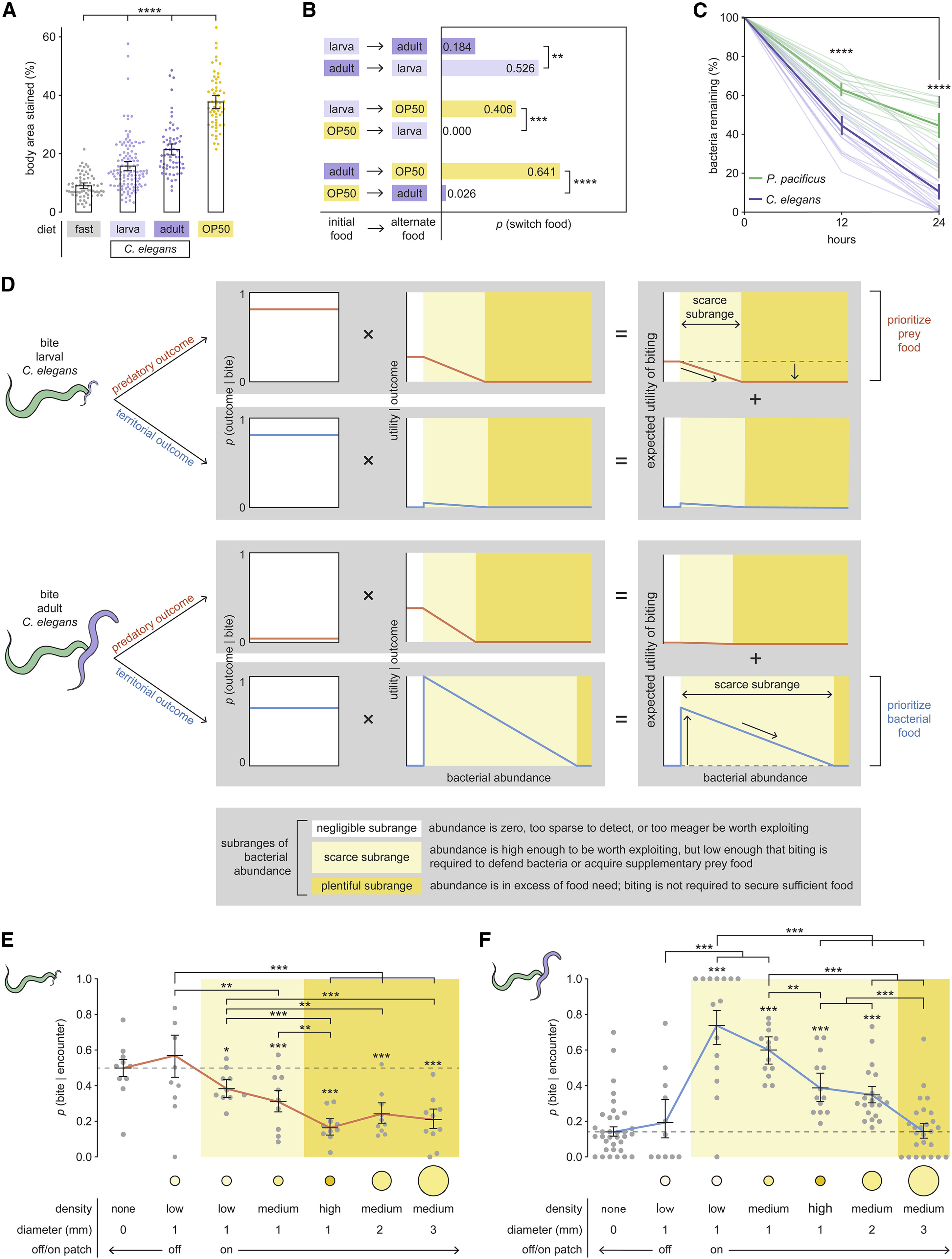

The cost of biting is less time spent eating. The benefit of biting depends on the intended outcome. If, for example, the intended outcome is killing C. elegans, then the benefit is a new source of food (i.e., a dead C. elegans). On the other hand, if the intended outcome is to chase C. elegans away, then the benefit is defending something both worms value (i.e., bacteria). The researchers found that adult C. elegans consumed bacteria about 1.5 times faster than P. pacificus. This suggests that time spent chasing off adult C. elegans is time well-spent under certain circumstances.

The researchers hypothesized that P. pacificus weighs its decisions based on how many bacteria are available and the type of C. elegans involved (adult or larva). If there is an overabundance of bacteria, biting is a waste of time. P. pacificus should just focus on eating and not spend time biting. If there are only few bacteria, then it is important to find more food and defend what little is available. So P. pacificus should bite larval C. elegans (for food) and adult C. elegans (to chase them away from the precious bacteria). If there are no bacteria, the territory is not worth defending; instead, P. pacificus should focus on biting larval C. elegans.

To test this, they placed P. pacificus in an arena with varied abundance of bacteria and either larval or adult C. elegans. They found that P. pacificus engaged a kill-and-eat strategy against larval C. elegans, which is easily killed and does not consume much bacteria. P. pacificus bit most when there was no bacteria and bit less as bacterial abundance increased.

Alternatively, P. pacificus deployed a territorial defense strategy against adult C. elegans, which is difficult to kill and rapidly consumes bacteria. P. pacificus bit most when bacteria were scarce and bit least when bacteria were absent or plentiful. Non-fatal bites effectively expel competitors from their territory. Altogether, this illustrates that P. pacificus weighs costs and benefits to determine what it should bite.

“Our study shows you can use a simple system such as the worm to study something complex, like goal-directed decision-making. We also demonstrated that behavior can tell us a lot about how the brain works,” says Sreekanth Chalasani, senior author of the study. “Even simple systems like worms have different strategies, and they can choose between those strategies, deciding which one works well for them in a given situation. That provides a framework for understanding how these decisions are made in more complex systems, such as humans.”