4 classic books that teach deep insights through unlikable protagonists

- Storytellers are often advised to create likable protagonists their audience can root for.

- But unlikable protagonists can be just as interesting, partly because they can teach important lessons in unexpected ways.

- From Dorian Gray to Anna Karenina, here are a few examples from literature.

In his book, Save the Cat!, Blake Snyder offers storytelling tips for aspiring screenwriters. His main piece of advice, from which the book gets its title, is to “save the cat.” In short, Snyder argues that writers should introduce their protagonists by having them do something that demonstrates their key traits or moral code, which sometimes means the character does something to make the audience like them—like saving a kitten from a tree. Likable characters, after all, can produce more compelling stories than unlikable ones.

Snyder has a point. Likable protagonists engage the audience by making it easier to relate to their personalities and struggles. The more we root for a character, the happier we feel when they accomplish their goal and the sadder we get when they don’t. Unlikable protagonists, by contrast, risk alienating their audience. At worst, we don’t care if they fail or succeed. At best, we actively want them to fail.

That said, Save the Cat! has given unlikable protagonists a bad reputation they do not deserve. When constructed well, they can be more gripping and memorable than likable ones—especially when their stories are about seeking redemption (think Rodion Raskolnikov from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment) or falling from grace (Lucifer in John Milton’s Paradise Lost).

Moreover, unlikable protagonists can impart valuable lessons that likable ones cannot. They can teach by negative example—by showing what happens when we make poor choices in life. They can also make us question the social standards, or force us to see the world from a different perspective and recognize that hints of humanity can be found in the unlikeliest of places.

Broken mirrors: Mr. Stevens and Dorian Gray

Unlikable main characters come in many different shapes and sizes. Some are vain, selfish, and arrogant, while others are humble and altruistic to the point that they annoy everyone around them. Unlikable protagonists can range from cold-blooded psychopaths who lack emotions to somewhat decent individuals destroyed by their own limited worldviews.

This last description applies to Mr. Stevens, the protagonist British-Japanese author Kazuo Ishiguro’s 1989 novel The Remains of the Day. Stevens, a butler whose unrelenting pursuit of “dignity” and loyal servitude leads him to suppress his own emotions, ultimately regrets his failure to establish authentic relationships. His character serves as a cautionary tale to readers.

Another main character who teaches by negative example is Dorian Gray, the protagonist of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. A narcissistic aristocrat whose handsome appearance masks the ugliness of his soul, Gray is so obsessed with his own image that he not only causes his lover to commit suicide but also interprets her death as adding color and drama to his own life story.

Although Wilde’s novel was initially interpreted as an endorsement of Gray’s hedonism and aestheticism—a movement in Victorian England which held that art should aim for beauty instead of truth, and should not comment on morality or politics—the sheer unlikability of the protagonist has led subsequent generations of critics to proclaim the novel a critique instead.

Uncomfortable truths: Anna Karenina

Lists of unlikable literary characters rarely mention novels by Leo Tolstoy, and for good reason. The Russian writer, among the greatest of all time, so thoroughly communicated the emotional states of his characters that readers cannot help but empathize with them, no matter how flawed they are. So great were Tolstoy’s talents that many women gasped at his ability to describe the inward experience of giving birth.

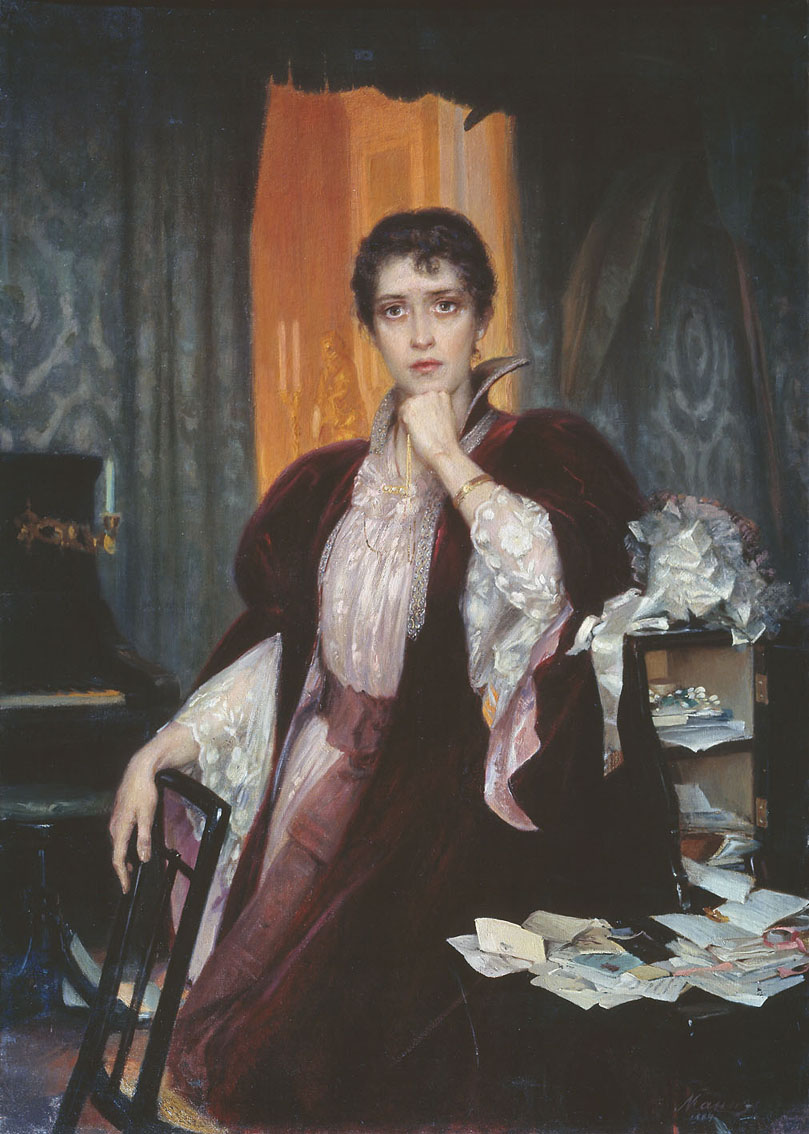

If you do find Tolstoy on one of these lists, chances are it’s because of Anna Karenina. Many readers, male and female, report frustration with the titular heroine’s volatile attitudes toward her estranged husband, as well as Vronsky, the dashing officer with whom she starts an affair. “She seemed like a capricious child,” one reviewer shares on Goodreads, “lamenting the consequences of her actions.”

But Karenina’s seemingly inconsistent behavior—disgust for her kind and forgiving husband, and jealousy toward her at times unavailable paramour—is simply a reflection of the complex and contradictory desires that exist inside a person’s soul. A major theme in the novel is that there are different kinds of love and that a person can feel multiple at the same time.

Just as The Picture of Dorian Gray has been mistakenly considered to endorse hedonism, Anna Karenina has been promoted—by Oprah Winfrey’s book club, among other groups—as an affirmation of romantic love. In fact, it is a moral tale cautioning against its temptations. The affair between Karenina and Vronsky goes to show that hopeless romantics love not each other, but the ideal of romantic love itself.

Tolstoy, who was deeply religious, presents an alternative through the marriage between Kitty, a princess, and Levin, her suitor. Their relationship, unlike Karenina and Vronsky’s, is based not on passion but on self-awareness, commitment, and mutual sacrifice. When Levin first proposes to Kitty, she rejects him; it is only after extensive introspection that she agrees to become his wife.

The case of Humbert Humbert

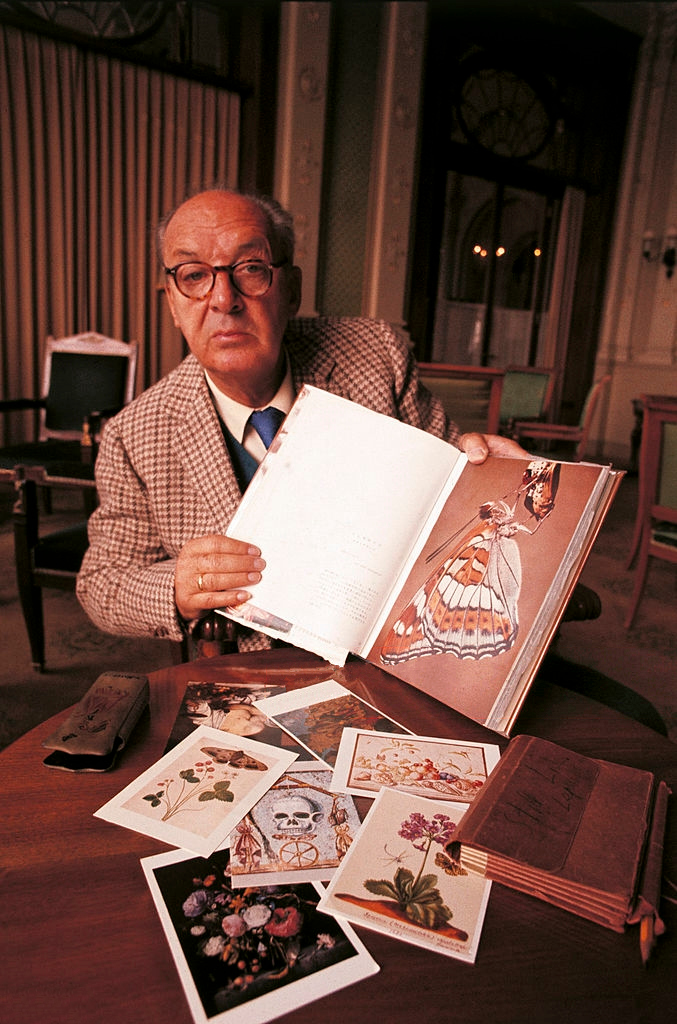

No discussion about unlikable protagonists from world literature would be complete without the inclusion of Humbert Humbert, the protagonist of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. In the infamous novel, told entirely from the protagonist’s perspective, Humbert attempts to explain why he, a 37-year-old man, sexually assaulted the 12-year-old Dolores Haze, nicknamed Lolita.

Apart from the revolting descriptions of predation, the most shocking aspect of the narrative is the length to which Humbert—and, by extension, Nabokov—goes to normalize his pedophilic attraction toward Lolita.

Not that this is what Lolita ends up doing. Far from demanding sympathy for Humbert Humbert, the novel tests the reader’s ability to withstand his charm and eloquence and recognize him for the monster that he really is. After finishing the novel, you’ll not only better understand how some pedophiles think and act, but also how they manipulate their victims—the reader included.

“Your run-of-the-mill obscene masterwork,” Stephen Metcalf surmises in an article for Slate, “demands that you, enlightened reader, work your way past the sex and excrement to recognize how beautiful it is. But with Lolita, you must work past its beauty to recognize how shocking it is. And for all its beauty, for all its immense ingenuity and humor, one easily forgets how shocking Lolita is.”