5 classic books that were loved by readers but panned by critics

- The subjective nature of what makes a great book has led to a surprising number of classics initially receiving mixed or negative reviews from critics.

- Over time, the critics often come to appreciate these works, siding with the readers who loved them from the start.

- From The Sun Also Rises to One Hundred Years of Solitude, here are five literary classics that were quick successes — just maybe not with the critics.

What makes for a great book is a somewhat subjective question. There are a surprising number of cases where books now held to be classics of the genre were initially greeted with mixed or outright negative views. But as time went by, the critics tended to side with the readers who loved them from the start.

Here are five great books that were loved by readers but panned by critics around the time they were published.

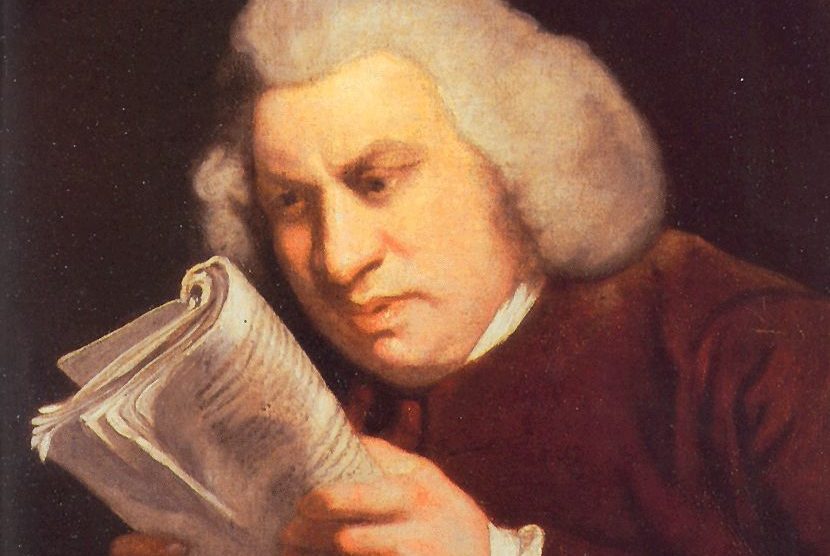

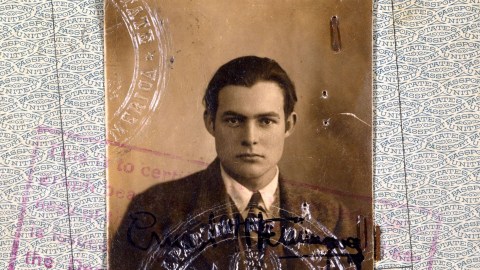

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

A roman à clef novel following American and British expats in Europe in the twenties, The Sun Also Rises explores the situation facing the Lost Generation in a world forever changed by WWI and the advent of modernity. The book sold rapidly, and a second printing was ordered two months after publication. It has never been out of print and is considered by many critics to be one of his best works.

But not all critics were so taken with the book. One review published in The Nation argued that Hemingway “doesn’t fill out his characters and let them stand for themselves,” adding that the book was sentimental and Hemingway seemed to consider himself “morally superior.” Hemingway’s family also detested the book. His mother wrote to him to express her displeasure at how “Every page fills me with a sick loathing.”

While modern reviewers tend to be more favorable to the novel, they often take issue with the depiction of Jewish characters, homosexuality, and women.

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

One Hundred Years of Solitude follows seven generations of the Buendia family of Macondo, Colombia. Blending magical realism alongside events in Colombian history, the novel explores ideas of history and time, solitude, fate and free will, and elitism. Published in 1967, it proved extremely popular, well beyond what was needed to secure an international release.

While the book helped Márquez earn a Nobel Prize for Literature and praise as “The greatest Colombian who ever lived,” much of the initial critical reception to his masterpiece was negative. One review dismissed it as a “comic masterpiece.” Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz deemed it “watery poetry.” Anthony Burgess argued that it was not to be “compared with the genuinely literary explorations of Borges and Nabokov.”

The positive reviews arguably won out. One Hundred Years of Solitude is now considered a classic of Latin American literature and one of the best examples of magical realism.

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

The Grapes of Wrath follows the Joad family in Oklahoma during the Great Depression. With their farm devastated by the Dust Bowl, they join thousands of people like them west to California, an alleged land of milk and honey. However, they find only new problems upon arriving. The book was the best-selling novel of 1939. Its popularity led it to be made into a film the next year directed by John Ford and starring Henry Fonda.

Reactions to the book were extremely divided. Copies were burned by those denouncing Steinbeck as a socialist. Many libraries refused to carry the book. One sitting congressman argued that the book “exposes nothing but the total depravity, vulgarity, and degraded mentality of the author.” Steinbeck was particularly troubled by critics that claimed he had written an overly sentimental novel or that he was lying about the conditions facing families like the Joads.

While the occasional negative review still pops up, the book is now considered a classic of American literature. It won the Pulitzer Prize and was cited as a factor in awarding Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize.

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

To Kill a Mockingbird is the story of how an innocent man is defended in both the courts of law and public opinion by a particularly virtuous lawyer, Atticus Finch, in depression-era Alabama, as seen through the eyes of his daughter, Scout. It explores questions of race, class, gender roles, and the loss of innocence in a way that has resonated with readers since it was published in 1960.

The book proved difficult for Ms. Lee to write and publish. She was warned that it was unlikely to sell. This proved incorrect. Mockingbird was reprinted by Reader’s Digest and earned a vast readership from the start. It is estimated to have sold 30 million copies and is a beloved piece of American literature.

While modern reviews of the book are generally glowing, early reviews were decidedly mixed. Short story author Flannery O’Connor deemed it a “child’s book” and was confused by the number of people who praised it as adult literature. Novelist Granville Hicks deemed it “melodramatic and contrived.” A review published in The Atlantic found Scout’s tendency to speak like an adult “implausible” while finding the book “pleasant” on the whole.

Even today, negative reviews still crop up. More recent ones tend to target the book’s take on race and class, which were once thought so progressive. Others provide an alternative analysis of the characters — especially of Atticus Finch.

Les Misérables by Victor Hugo

An epic story with numerous subplots, Les Mis centers on the story of Jean Valjean as he tries to overcome his criminal past. Along the way, he encounters unscrupulous inn owners, revolutionary college students, an extremely determined police inspector, and a little girl, Cosette, to whom he devotes his life.

Hugo was already a household name, thanks to The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and his new releases were highly anticipated. As such, it is unsurprising that Les Mis was immediately popular and was translated from French into a number of other languages shortly after its initial release.

Despite the extreme anticipation for the book, initial critical reviews skewed negative. The French novelist Gustave Flaubert described it as “infantile” and predicted it would end Hugo’s career. Poet Charles Baudelaire publicly praised parts of the novel while privately dismissing it as “repulsive.” The Catholic Church included it on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, forbidding any Catholic from reading it. Other reviewers found it overly sentimentalist and subversive.

The reviews improved in the subsequent decades. Upton Sinclair would call the book “one of the half-dozen greatest novels of the world.”