What shaped Kurt Vonnegut’s warped conception of time (and death)?

- The writing of Kurt Vonnegut is heavily influenced by his experience in World War II.

- Unable to relegate his wartime memories to the past, Vonnegut began thinking of time in a non-linear fashion.

- His stories are about people who can perceive all of the spacetime continuum at once, traveling from past to present to future.

“Stephen Hawking, in his 1988 bestseller A Brief History of Time, found it tantalizing that we could not remember the future,” Kurt Vonnegut writes in the introduction of his book Slaughterhouse-Five. “But remembering the future is child’s play for me now. I know what will become of my helpless, trusting babies because they are grown-ups now. I know how my closest friends will end up because so many of them are retired or dead now…”

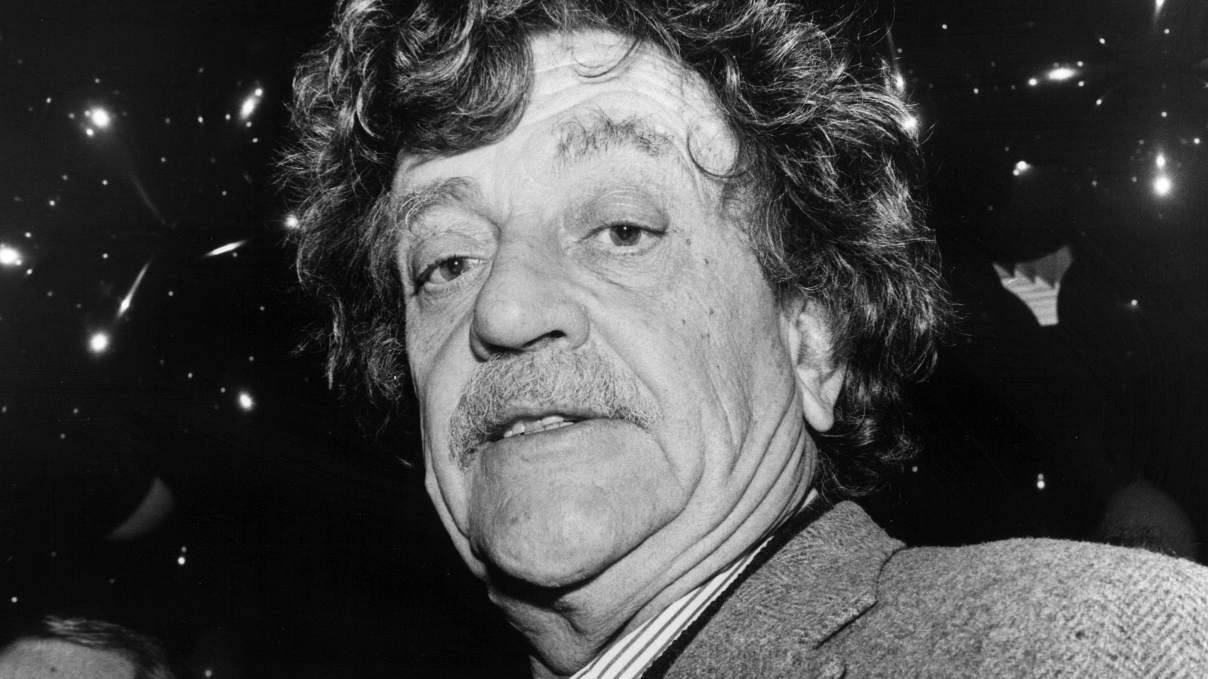

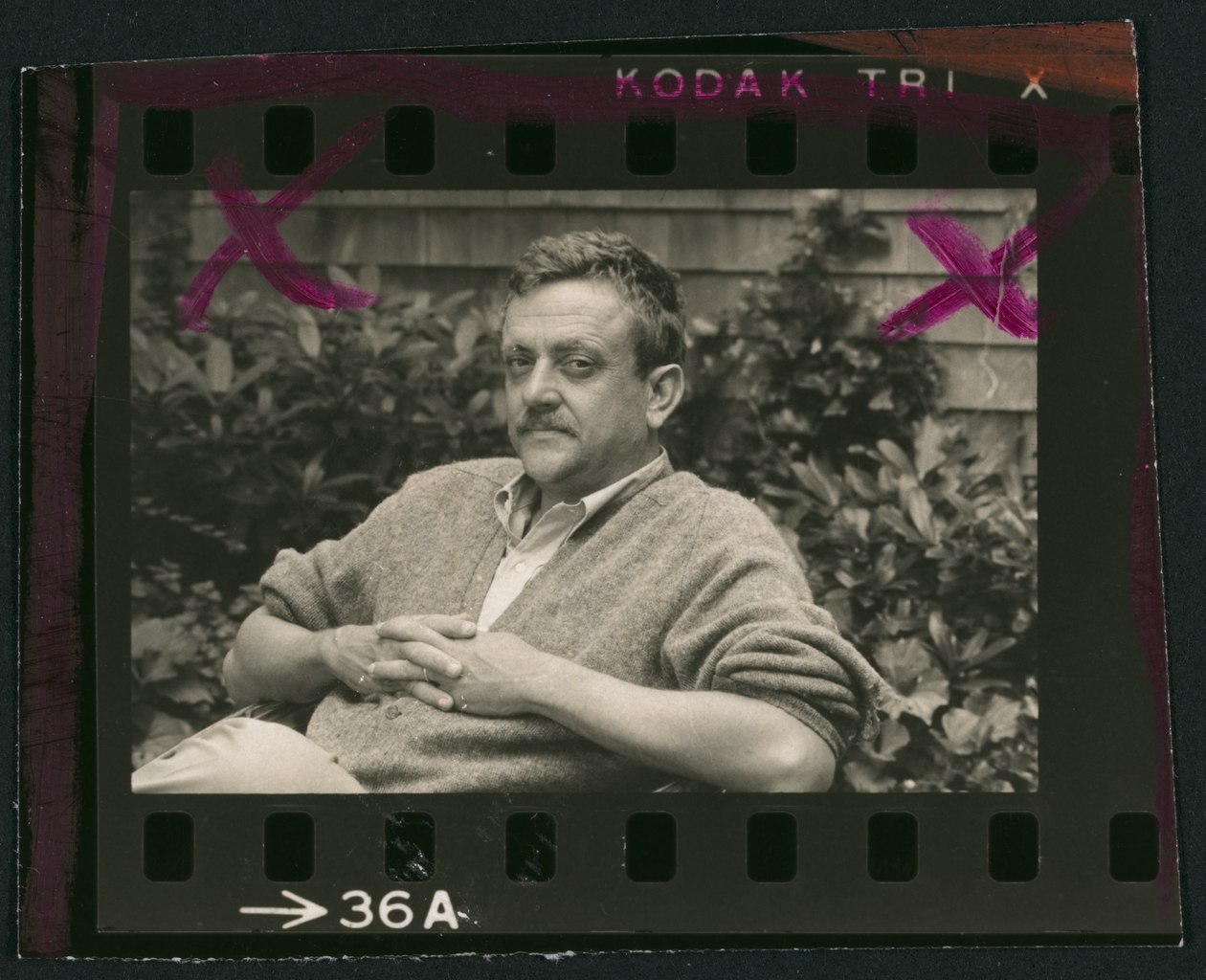

Kurt Vonnegut, a prominent American literary writer from the 20th century, uses simple diction and sentence structure to tackle infinitely complex questions. From Harrison Bergeron — set in a dystopian U.S. where smart people are made dumber to promote intellectual equality — to Cat’s Cradle, which is about the search for a world-ending superweapon, Vonnegut’s novels are typically about characters grappling with the idea that they lack control over their own destinies.

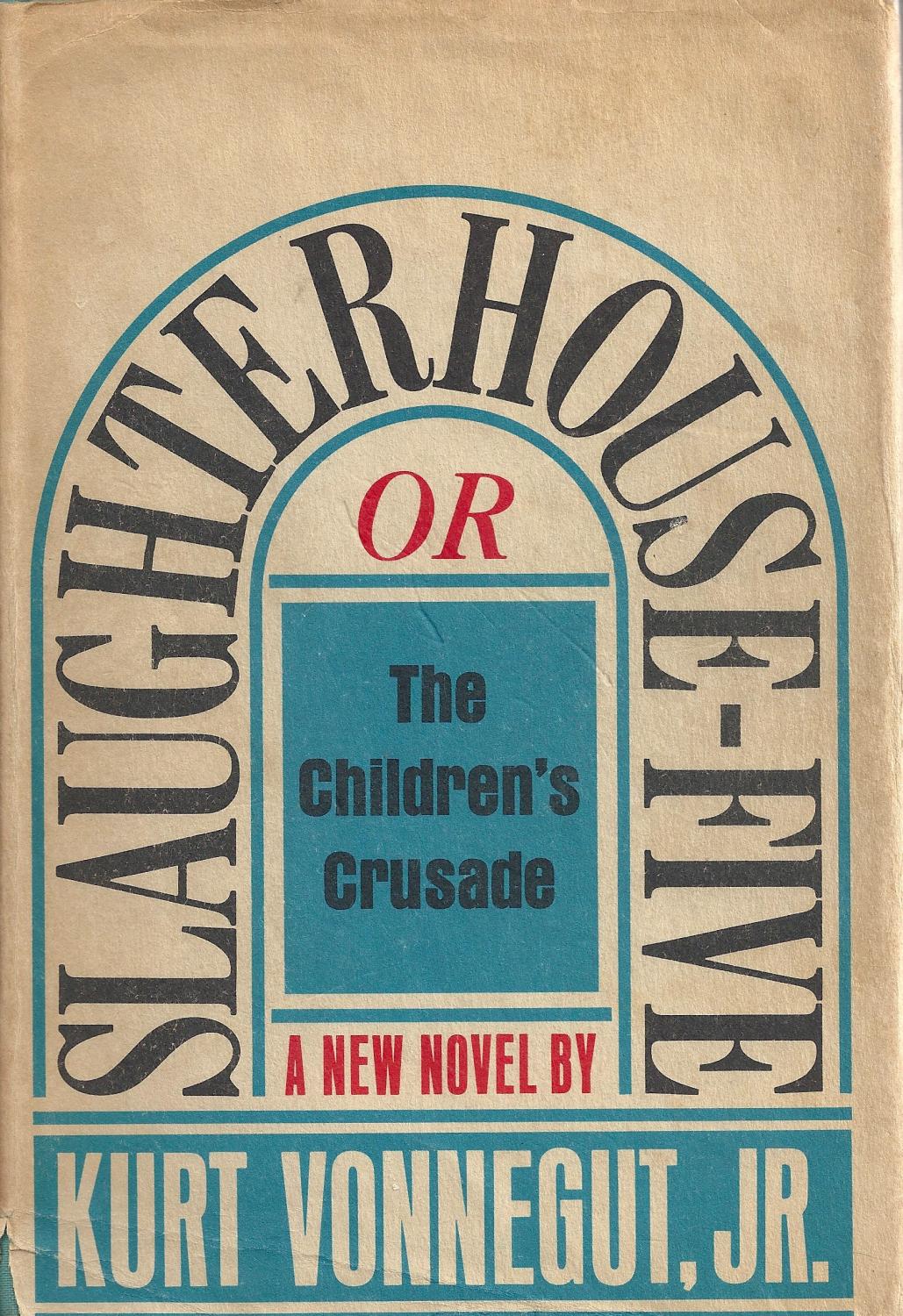

Slaughterhouse-Five, his most famous work, follows a World War II soldier who is taken prisoner by the Nazis and narrowly survives Allied bombings on the city of Dresden. Years later, the soldier — named Billy Pilgrim — is abducted by flying saucer and taken to the planet Tralfamadore, where he is placed inside a zoo for the entertainment of plumber-shaped aliens capable of perceiving all of the spacetime continuum at once.

Because Vonnegut is a deeply ironic and black-humored writer, some readers believe Billy, whom we are told suffers from PTSD, did not actually visit Tralfamadore. Rather, they argue that the episode is a hallucination created by his mind to process traumatic memories from the war. However, according to Salman Rushdie, who wrote an article about Slaughterhouse-Five for The New Yorker, this interpretation does not hold up.

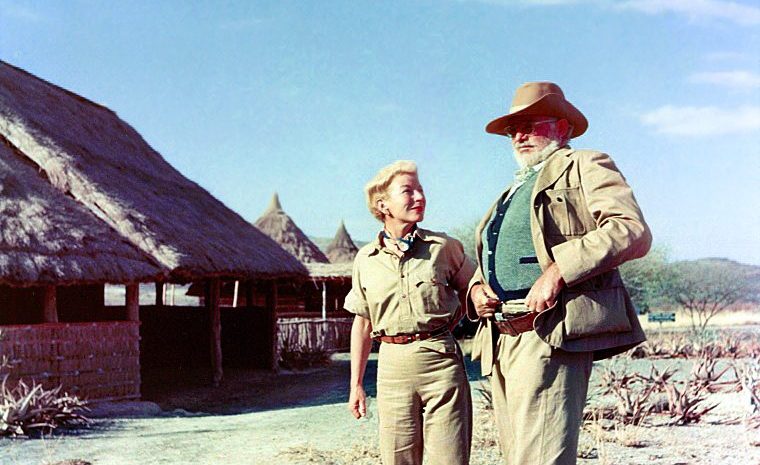

“The truth,” writes Rushdie, “is that ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ is a great realist novel.” Kurt Vonnegut not only appears inside the novel as narrator, but also bases the plot on his own wartime experiences. Like Billy, Vonnegut was drafted into the Second World War and sent to Europe, taken prisoner after the Battle of the Bulge, and thrown into a subterranean slaughterhouse in Dresden, which, in an absurd twist of fate, allowed him to survive the bombing.

Time on Tralfamadore

Dresden drastically changed Vonnegut’s perception of time, a concept that most of us rarely think about. In the underground slaughterhouse, Vonnegut clearly felt the difference between objective time — the kind of time that is represented on a clock — and subjective time, which is perceived differently by each individual; listening to the explosions and awaiting the possibility of his death, Vonnegut felt as though each passing second lasted an eternity.

That was not all. Later in life, Kurt Vonnegut was unable to relegate his memory of the bombing to the past. Instead, the trauma stayed with him in the present, lodged in his subconscious. Whenever he thought back of that faithful day, it was as if he were traveling back in time itself. “Nothing in this world is ever final,” Vonnegut said in a 1970 New York Times interview, “no one ever ends – we keep bouncing back and forth in time, we go on and on ad infinitum.”

In his novel, The Sirens of Titan, Vonnegut contrasts his alternative, non-linear understanding of time with the conventional, linear understanding held by most of his readers. The novel revolves around the discovery that the evolution of human civilization has been manipulated by an alien race from a distant galaxy to one day produce a small spare part for the spaceship of an intergalactic messenger stranded on Saturn’s second-largest moon.

Linear time is represented by the novel’s protagonist, Malachi Constant, and his son Chrono, who ultimately delivers the messenger’s spare part. Constant and Chrono view time as a straight line that moves from cause to effect, and cannot imagine time any other way. The novel presents this viewpoint as limiting. “Subject to this harsh determinism,” writes Philip Rubens in Nothing’s Ever Final, mankind “is trapped in a universe that closely resembles [the Greek concept of fate].”

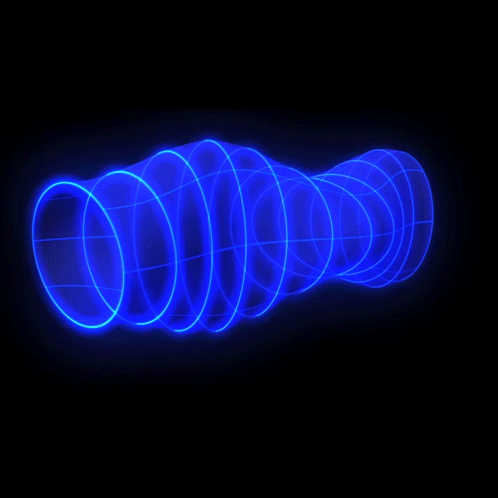

Kurt Vonnegut’s alternative understanding of time is represented by another character named Winston Niles Rumfoord, a rich New Englander who, while traveling through space in his private spaceship, crosses the Chrono-Synclastic Infundibulum, a dimension that causes Rumfoord to become “unstuck in time.” Transformed into a wave phenomenon, Rumfoord disappears and reappears in in different places throughout the past, present, and future.

In Sirens of Titan, Rumfoord tries to explain his existence — which is not unlike that of the denizens of Tralfamadore — to his wife Beatrice. “Look,” he says, “life for a punctual person is like a roller coaster…I can see the whole roller coaster you’re on. And sure – I could give you a piece of paper that would tell you about every dip and turn…But that wouldn’t help you any…Because you’d still have to take the roller coaster ride.”

Kurt Vonnegut: time and death

Vonnegut’s non-linear understanding of time, expressed through Rumfoord in Sirens of Titan and the Tralfamadorians in Slaughterhouse-Five has its advantages. “Time,” argues one critic, “since it leads inevitably to death—is the real enemy of Vonnegut-as-character. Death seems too real for Vonnegut to omit from his reinvented cosmos, but by reinventing the nature of time, Vonnegut deprives death of its sting.”

Again, Kurt Vonnegut’s characters help illustrate this abstract concept through their choice of words. “The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore,” says Billy, “was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past (…) All moments past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist…When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments.”

Rumfoord reaches the same comforting conclusion. “Everything that ever has been always will be,” he declares, “and everything that ever will be always has been.” He adds: “I am not dying…In the grand, in the timeless, in the chrono-synclastic infundibulated way of looking at things, I shall always be here. I shall always be wherever I’ve been. I’m honeymooning with you still, Beatrice…I’m talking to you still in a little room under the stairway in Newport, Mr. Constant.”

Kurt Vonnegut’s understanding of time has another benefit: It offers reprieve from the deterministic way of thinking that is seen so often (and weaponized) in times of war. “He [Vonnegut] had a horror of people who took things too seriously,” Rushdie says, adding:

“And was simultaneously obsessed with the consideration of the most serious things, things both philosophical (like free will) and lethal (like the firebombing of Dresden). This is the paradox out of which his dark ironies grow. Nobody who futzed around so often and in so many ways with the idea of free will, or who cared so profoundly about the dead, could be described as a fatalist, or a quietist, or resigned. His books argue about ideas of freedom and mourn the dead, from their first pages to their last.”