Out for blood in the search to stall aging

Last year, two self-described “biohackers” in Russia had themselves hooked up to blood collection machines that replaced approximately half of the plasma coursing through their veins with salty water. Three days later, the men tested their blood for hormones, fats and other indicators of general well-being. The procedure, it seemed, had improved various aspects of immunity, liver function and cholesterol metabolism.

“The data we obtained demonstrate the potential therapeutic effect of plasma dilution,” the men wrote (in Russian) on their group’s website.

The practice of removing and replacing blood plasma, the yellowish liquid component of blood that carries cells and proteins throughout the body, has a long history in the treatment of autoimmunity. But the aim for the men, both in their fifties, wasn’t about dealing with a disease. Instead, they were self-experimenting with an offbeat proposal for fighting the aging process — the latest in a line of scientific efforts to harness the supposed rejuvenating properties of young blood.

From Greek mythology to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, tales of blood’s restorative powers have captured the human imagination for millennia. But in the past two decades, the idea of blood as an elixir of youth has leapt from the pages of storybooks and ancient folklore into the medical mainstream, with high-profile papers demonstrating the regenerative capacity of young blood in aged mice. Those have also led to the launch of several new biotech start-ups that aim to combat Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, stroke and other diseases of aging by revitalizing our most essential of bodily fluids.

Some companies hope to give patients fractions of youthful blood plasma or to administer lab-grown versions of proteins found naturally therein. Others are focused less on promoting the good parts of young blood and more on blocking (or diluting) the ill effects of old blood. Still others are looking for factors in the blood of “super agers” — senior citizens who live without substantial physical or cognitive impairments, despite their advanced years — that might explain their longevity and could be replicated with a drug.

The research remains in its infancy, with more evidence in mice than in people that the therapies work. And experts caution that further testing in clinical trials is needed to ensure that any blood-informed treatment is safe and effective. Still, that hasn’t stopped renegade biohackers and rogue transfusion clinics from moving ahead with the proposed interventions anyway — much to the consternation of regulators, ethicists and scientists.

Here, Knowable Magazine takes a look at the origins of this controversial science, the variety of approaches being pursued by the companies involved, and where the anti-aging strategy could be headed as the field matures.

A stitch in time

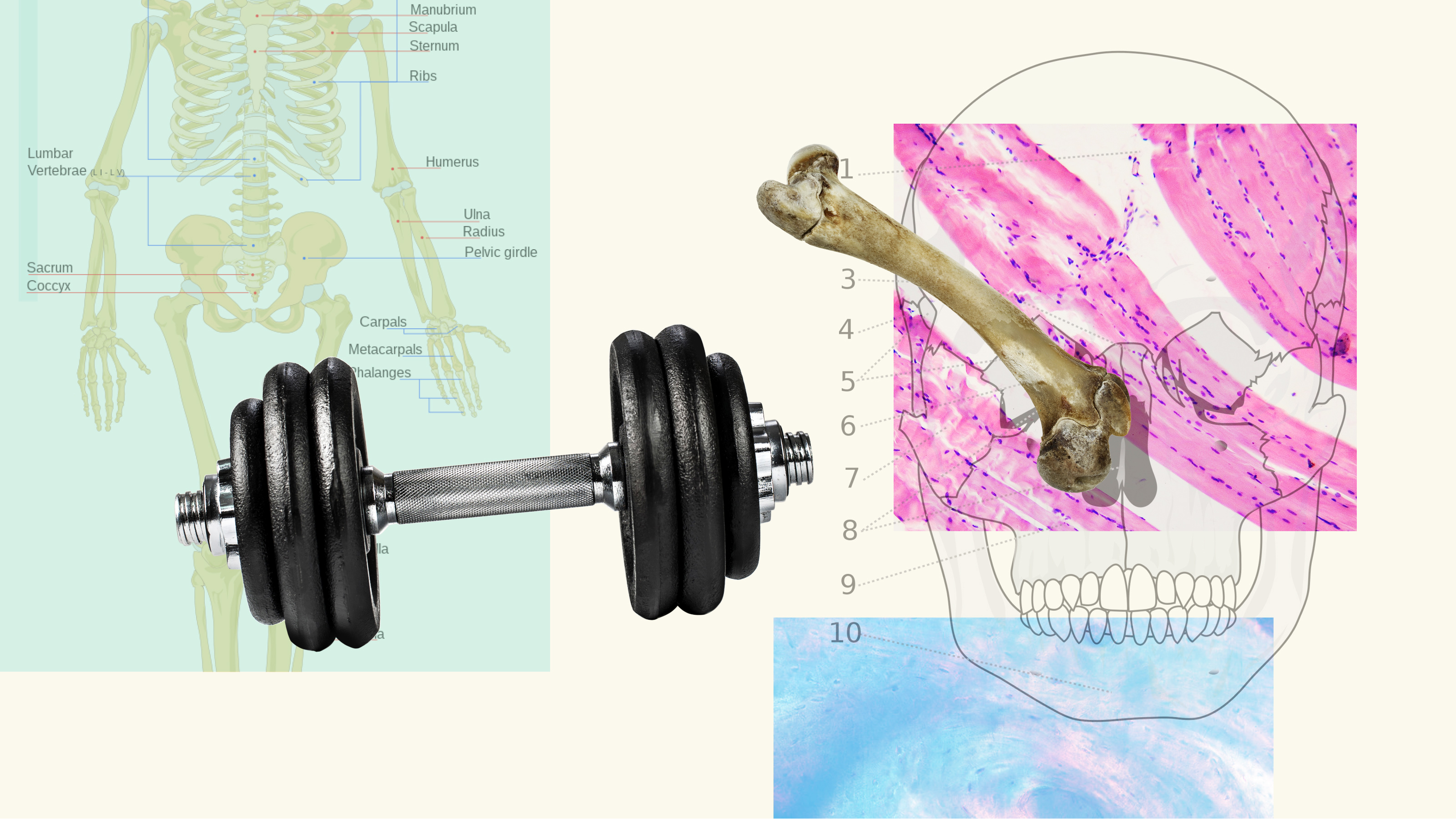

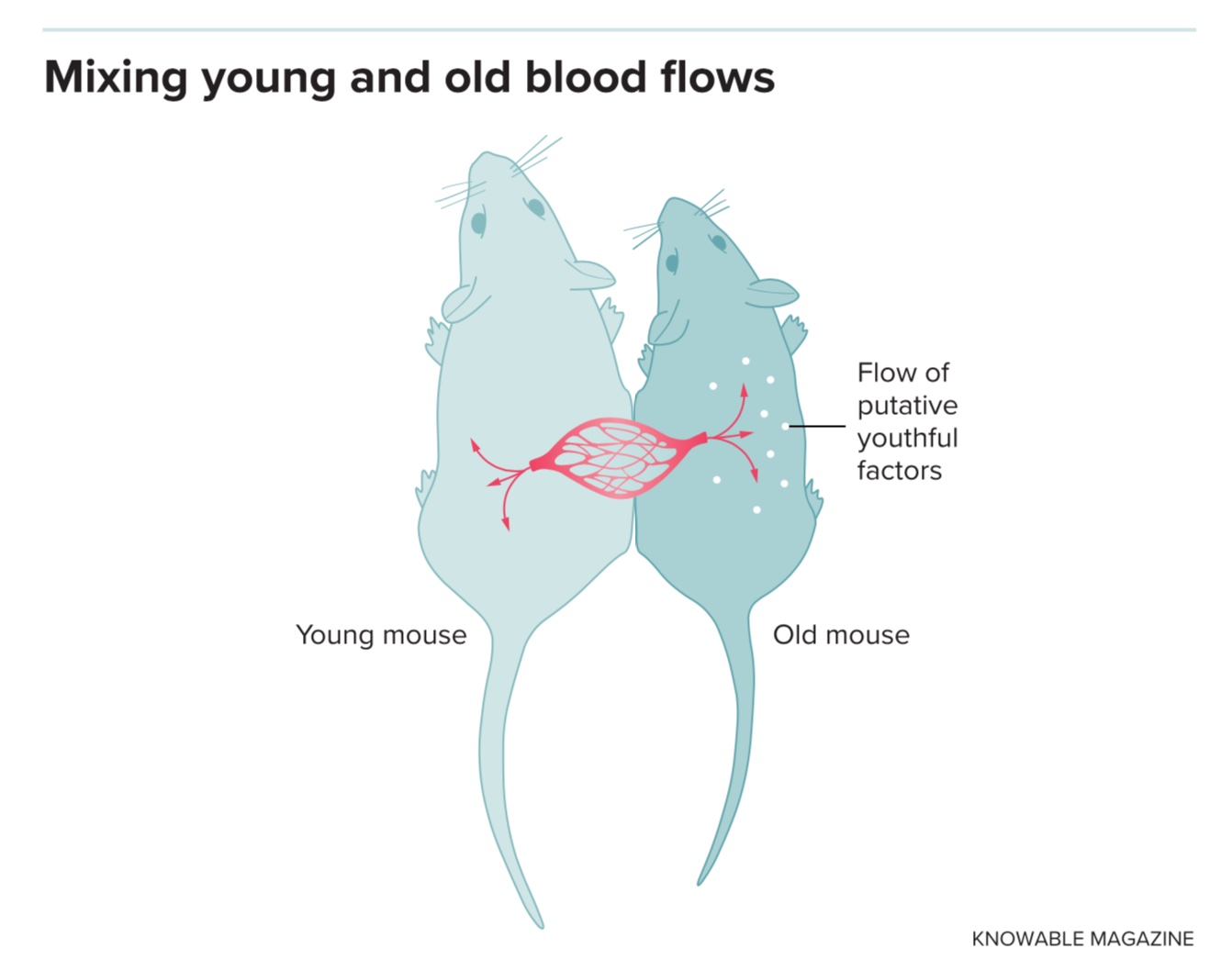

The first signs that young blood could blunt the ravages of aging came more than 60 years ago when a team at Cornell University — using a somewhat ghoulish procedure devised a century earlier and used to study wound healing — sutured together two rats so that they would share a common circulatory system. After old and young rats were joined for many months, the bones of both animals became similar in weight, volume and density, thus helping to ward off the bone brittleness that typically accompanies old age.

Some 15 years later, researchers at the University of California performed their own old–young rat pairing experiments. As they reported in 1972, older partners in this arrangement lived around 10 to 20 percent longer than control rats paired to other old animals.

The rodent-conjoining technique, known as parabiosis, then fell out of favor for many years. That is, until the beginning of this century, when scientists working in three different laboratories at Stanford University collectively revived the approach. Many of those same scientists would go on to create the competing companies that have become synonymous with young-blood therapeutics today.

First, a group led by Amy Wagers and Irv Weissman used parabiotic mice to track the fate and movement of blood stem cells. That research wasn’t focused on aging, but their method captured the imagination of two other Stanford scientists who studied longevity, Irina and Michael Conboy — a wife-and-husband duo working in the lab of Thomas Rando at the time. They learned the method from Wagers and went on to show that young blood could rejuvenate tissue-specific stem cells that had grown sluggish with age. By uniting the circulatory systems of young and old mice, the Conboys restored youthful molecular signatures in the aged animals and reactivated the regenerative capacity of various organs, including muscle and liver.

Two more scientists at Stanford, Tony Wyss-Coray and Saul Villeda, then extended those findings to the brain, reporting that young blood transmitted via parabiosis enhanced the production of new neurons, a process that is usually in decline in old age. The same team later showed that injections of young blood plasma alone were sufficient to produce similar effects.

The drivers of these rejuvenating effects remain somewhat mysterious, but there are several leading molecular candidates. Irina Conboy, after she and Michael moved to UC Berkeley, showed that oxytocin — a hormone best known for helping with childbirth and breastfeeding — also promotes muscle stem cell regeneration in an age-specific fashion. Wyss-Coray’s lab detailed the brain-revitalizing effects of TIMP2, another blood-borne factor enriched in young plasma. And Wagers, who started her own group at Harvard, focused on a protein called growth differentiation factor 11, or GDF11, which seemed to improve aspects of age-related heart disease, neurodegeneration and muscle wasting.

Wagers went on to form a company called Elevian that now plans to test whether factory-produced versions of GDF11 can help treat stroke and other age-related diseases. Wyss-Coray, meanwhile, started Alkahest, a company focused in large part on administering young plasma preparations to people with dementia and other brain disorders.

Start-up rundown

Conceptually, the therapeutic strategies of these two front-runner start-ups could not be further apart. On the one extreme is Elevian’s reductionist approach, which attempts to recapitulate the benefits of young blood through supplementation with a single pro-youthful factor. On the other is Alkahest’s plasma formulations, created by pooling blood from multiple young donors and then sorting the contents to remove unwanted immune molecules. (A company called Nugenics Research has its own proprietary plasma-derived product, termed Elixir, in development as well.)

Neither strategy is necessarily ideal from a scientific perspective, experts say. One may be too simplistic, the other too complex.

“It’s probably not a single factor that drives aging or a single factor that can rejuvenate tissues,” says Paul Robbins, a molecular biologist who studies aging at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis. (Robbins discusses another hot area of anti-aging research, one that involves purging the body of dying “senescent” cells, in the 2021 issue of the Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology.) “It’s going to have to eventually be a cocktail of things that people take,” he says — but finding the ingredients that should go into that cocktail, and then creating relevant therapeutics, remains a tall order.

“It’s probably not a single factor that drives aging or a single factor that can rejuvenate tissues.”

PAUL ROBBINS

Several blood-borne proteins have been implicated in the aging process. And it’s unclear which, if any, of these pro-aging factors or youth-associated factors can be blocked or activated, respectively, in ways that can safely stem the cellular march of time in our bodies.

Many of those same factors may also counteract each other when combined, or confer unwanted side effects, especially when given over a prolonged period. That’s a concern when administering ill-defined soups of plasma proteins, as is the case with Alkahest’s plasma preparations, which contain over 400 such constituent parts. “It’s surprising that, in a time when you can actually develop really precise technologies, you would just use crude preparations,” says Dmytro Shytikov, an immunologist at Zhejiang University’s international campus in Haining, China, speaking of plasma-based products in general.

In their defense, Alkahest executives point to early clinical data that hint at potential therapeutic benefits of the company’s plasma-derived products. Although the trials to date have been small and not always placebo-controlled, those studies suggest that people with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s who received the plasma preparations seemed to experience some positive cognitive effects.

Hedging its bets, though, Alkahest (now a subsidiary of the Spanish pharma company Grifols after a $146-million buyout last year) is also advancing a more conventional therapeutic substance alongside its plasma extracts. Based on results in mice from Wyss-Coray and Villeda that an immune signaling molecule found circulating in old blood contributes to impaired learning and memory, the company designed a twice-a-day pill that blocks one of this molecule’s key receptors. That drug has shown early promise in people with age-related macular degeneration, a leading cause of blindness. A trial is ongoing for people with Parkinson’s, too.

Elevian is still a couple years away from testing its lab-grown version of GDF11 in human trials, but CEO Mark Allen remains confident in the company’s single-factor approach. While combinations of pro-youthful agents might be preferable, he acknowledges, “there’s nothing that’s been found that’s as potent in its effects as GDF11.” In rodent models at least, he says, the protein by itself can restore a youthful pattern of blood vessels in the brain following a stroke as well as promote improvements in motor control and other physical functions. Elevian raised $15 million last year to advance the therapy further.

Dilution solution?

Irina and Michael Conboy initially tried taking the reductionist drug development approach of Wagers and others. They identified two biochemical pathways implicated with aging, pharmacologically recalibrated both in old mice, and found that the animals’ brains, livers and muscles showed signs of rejuvenation.

But a more rudimentary intervention they tried did better still: In a series of experiments that inspired the Russian biohackers, the Conboys simply replaced half of the animals’ plasma with saline. (They, like the biohackers, also added back albumin, a protein essential for maintaining the proper fluid balance in the blood.) The dilution of pro-aging factors proved sufficient to activate a series of molecular changes in the mice that unleashed age-defying factors, leading to cognitive improvements and reduced inflammation in the brain, the Conboys found.

Although other researchers saw many of the same effects when they administered young blood to mice, Irina Conboy suspects that those benefits had more to do with the dilution of old plasma than any enrichments provided by the young plasma. “Basically, what this means is that we do not age because we run out of youthful factors, and we are not rejuvenated because we add youthful factors,” she says. On balance, her research suggests that the detrimental effects of circulatory proteins in old blood — which include the suppression of youthful factors — are far stronger than any rejuvenating qualities of molecules added via young blood.

Many age-elevated factors have been identified, but finding drugs for each one is a challenge. Plasma dilution, by comparison, knocks them all down — and others as yet unknown — in one fell swoop. The Conboys, together with blood specialist Dobri Kiprov from the California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, founded a company called IMYu to develop the plasma exchange strategy further.

Others feel similarly dubious about young blood as a therapeutic. “This approach reminds me of trying to refresh sour milk by pouring fresh milk into it,” says Iryna Pishel, who together with Shytikov previously tested the anti-aging effects of young plasma on old mice and saw little impact on lifespan or immunological markers of aging. Pishel now leads an applied pharmacology lab at Enamine, a contract research organization in Ukraine.

That hasn’t stopped some doctors from offering young blood transfusions anyway. That’s despite a 2019 warning from the US Food and Drug Administration that such treatments provide “no proven clinical benefit” against age-related ailments, and that “some patients are being preyed upon by unscrupulous actors touting treatments of plasma from young donors as cures and remedies.” Clinics such as the Atlantis Anti-Aging Institute in Florida and companies such as Ambrosia — which ships blood to physicians across the United States — continue to sell plasma from 16-to-25-year-old donors for several thousand dollars per transfusion.

Defending its practice, an Ambrosia spokesperson told Knowable that “plasma transfusions are FDA-approved in the United States and doctors are allowed to use approved treatments in new ways.”

“For the marketing of off-label treatments, we are allowed to state the facts,” the spokesperson added — but the company has not publicly released any clinical data to back its claims. “For now, we are keeping our results for the benefits of our doctors and patients.”

In the face of such secrecy, many researchers — including parabiosis pioneers such as Wyss-Coray and the Conboys whose work directly inspired Ambrosia’s creation — have publicly called the company “immoral” and “dangerous.” (“Frankly,” the spokesperson rebuts, “the reception we’ve received from the press, academia, pharmaceutical companies and government agencies has been unfair, unscientific and hostile.”)

(Knowable contacted the Atlantis Anti-Aging Institute for comment on its own treatments but received no reply. Their website carries this statement: “‘Young Plasma’ treatments are being used ‘off-label’ and must be considered ‘experimental.’ Plasma has been used safely for decades in every hospital in the world for many other ailments. Per FDA guidelines, we cannot make ANY claims of efficacy of these treatments.”)

Growing up

With all the controversies swirling around young plasma, some of the field’s biggest contributors have already moved on to other topics. Villeda, now running his own lab at UC San Francisco, is focused, among other things, on studying how exercise brings about changes in the blood that can combat brain aging. (In a 2017 article for the Annual Review of Neuroscience, he discusses evidence suggesting that both exercise and young blood can promote brain health.)

“Blood is our window into healthy human aging.”

KRISTEN FORTNEY

And though Rando continues to serve as a scientific advisor to Alkahest, his primary commercial interest has little to do with blood at all. Fountain Therapeutics, a company he cofounded in 2018, is targeting the aging process in cells, not the circulatory system.

Another biotech looking for anti-aging secrets in blood is centering its efforts entirely on the blood of the elderly, not the young. BioAge has partnered with research centers in Estonia and the United States to study blood samples from more than 3,000 older individuals, each person tracked over decades for indicators of age-related disease. By comparing the blood of healthy agers with those who show early signs of decline, the company has identified several molecular targets implicated in regeneration, immunity and muscle function. Drugs directed at all three targets are now in early testing for relevant age-associated conditions.

“Blood is our window into healthy human aging,” says Kristen Fortney, cofounder and CEO of BioAge. “We’re trying to learn from the example of humans that are living well.”

It’s a far cry from the vampire-like miracle cure of young blood, but BioAge’s approach might also be easier to translate into modern medicines. “To me, it’s the low-hanging fruit in anti-aging,” says Fortney. “Let’s copy what’s already working.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.