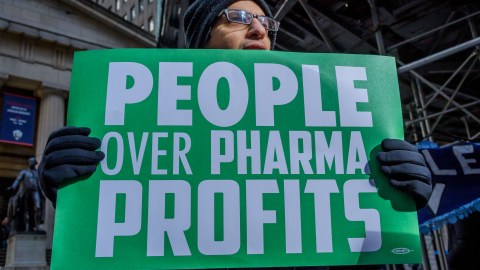

Illinois set to approve insulin price cap of $100 for month supply

Photo credit: Erik McGregor / Getty

- Some 30 million Americans have diabetes and must take insulin, but about 25 percent of them can’t routinely afford the drug.

- In recent decades, the cost of insulin has skyrocketed, partly because only three companies make insulin in the U.S.

- There’s some indication that recent efforts to make insulin more affordable are picking up steam.

Illinois is set to pass a measure to cap out-of-pocket insulin costs at $100 for a 30-day supply, a move that reflects a broader effort to lower costs of the hormone across the nation.

The bill is currently in the hands of Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, who has expressed support for capping insulin prices, saying the rising costs are “an enormous burden for too many Illinois families,” and that Illinois sees health care as “a right and not a privilege,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

The cap applies only to commercial insurance plans, and it was modeled after a bill in Colorado, which became the first state to cap insulin prices earlier this year. If passed, the Illinois bill would take effect Jan. 1, 2021.

“For over a million Illinois residents, insulin is an absolute necessity,” said State Sen. Andy Manar (D-Bunker Hill), who sponsored the bill. “Without it, they will die. Pharmaceutical companies are leveraging that fact in order to maximize profits. It’s time we hold them accountable.”

”Insulin belongs to the world, not to me”

Insulin is an essential and naturally occurring hormone that regulates blood sugar. About 30 million Americans have diabetes and must take insulin because they either don’t produce enough of the hormone or don’t respond to its effects. Before the discovery of insulin in the 1920s, a diagnosis for Type 1 diabetes was often considered a death sentence.

In 1923, Frederick Banting, James Collip, and Charles Best sold the first insulin patent to the University of Toronto for $1 each. They believed the drug — which meant Type 1 diabetes was no longer a death sentence — shouldn’t be kept from the public for the sake of profit.

“Insulin belongs to the world, not to me,” Banting reportedly said at the time.

But a century after their discovery, insulin is one of the most expensive liquids in the world, and it remains prohibitively expensive for millions of diabetes patients worldwide, many of whom risk facing blindness, strokes, foot amputations or premature death without access to the drug.

“You don’t know if you will have enough of a freaking liquid that your whole life depends on,” Marina Tsaplina, who has diabetes, told Business Insider. “You don’t know if you have enough life. That’s what being not sure if you can afford your insulin means.”

The insulin crisis

The soaring prices of insulin have sparked outrage. In 2016, the average monthly cost of insulin was about $450, but nearly 25 percent of Americans with diabetes are unable to routinely afford these prices, and so they resort to rationing, skipping doses or even obtaining insulin illegally.

What’s driving up prices? One explanation lies in the fact that there are only three major insulin makers in the U.S.: Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, each of which is able to negotiate drug prices with private insurers. These “big three” insulin makers have also been accused of price fixing in several lawsuits.

Typically, competing drug companies would be able to make generic versions of insulin, which would help lower prices. But no such generic insulin currently exists. That’s in part because insulin makers have made incremental changes to insulin drugs over the decades, which allow them to keep their designs protected by patent laws. Some of these changes have resulted in improved diabetes care. But others seem designed to extend patent protection.

The result is that it’s hardly profitable for alternative manufacturers to produce older versions of insulin.

“Older insulins have been successively replaced with newer, incrementally improved products covered by numerous additional patents,” states a 2017 Lancet paper on insulin price increases.

What’s more, navigating the patent laws is difficult and potentially dangerous for competing companies, as David Gaugh, senior vice president of sciences and regulatory affairs for the Association for Accessible Medicines, told STAT.

“There’s all types of patents that are involved,” Gaugh said. “Whether it be process patents, manufacturing patents, device patents É packaging patents, labeling patents and trademarks, all those are different methods used to prevent [competition].”

Patents aren’t the only factor preventing a generic insulin from entering the market. In fact, a true generic — or even biosimilar — insulin is impossible to create, according to U.S. law. That’s because generic drugs are derived from chemical-based medications, whereas insulin is a biologic-based drug. As such, any “generic” insulin is more complicated to manufacture and more difficult to get approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

More affordable insulin

In 2018, the American Diabetes Association recommended several steps U.S. lawmakers can take to make insulin more affordable:

- Streamlining the biosimilar process

- Increasing pricing transparency throughout the insulin supply chain

- Lowering or removing patient cost-sharing for insulin

- Increasing access to healthcare coverage

Earlier this year, members of Congress pressured the “big three” insulin makers, along with pharmacy benefit managers, to start lowering the costs of insulin. In November, the World Health Organization announced it would begin testing and approving generic versions of insulin, a process designed to make it easier for United Nations agencies and organizations like Doctors Without Borders to bring the drug to developing countries where it’s in short supply.

“Four hundred million people are living with diabetes, the amount of insulin available is too low and the price is too high, so we really need to do something,” Emer Cooke, the W.H.O.’s head of regulation of medicines and health technologies, said.

The director of the Affordable Insulin Now campaign, Rosemary Enobakhare, said in November that the W.H.O. move is “a good first step toward affordable insulin for all around the world,” but that it wouldn’t help diabetes patients in the U.S. To make a difference in the U.S., she said, would require “Congress to grant Medicare the power to negotiate drug prices” instead of leaving it up to insulin makers.