Being fit boosts your tolerance for cold weather

Photo: Shutterstock

- A new study on mice shows that exercise helps them shiver longer.

- Brown fat did not seem to be the deciding factor in the mice’s ability to combat the cold.

- The combination of exercise and brown fat is a more likely reason why we can endure extreme temperatures.

Scott Carney was skeptical when he first visited Wim Hof. Ice baths, hyperventilation, long breath holds, and scaling world-class mountains shirtless sounded suspect. Yet once he experienced the results of Hof’s unique training method, he was hooked. As he writes in What Doesn’t Kill Us:

There is an entire hidden world of human biological responses that lies beyond our conscious minds that is intrinsically linked to the environment.

“Hacking” your biology, as one popular sentiment goes, means discovering those hidden responses. In Hof’s method, this includes, at the entry level, daily ice baths or showers and a sequence of hyperventilations and breath retentions. If you’ve ever heard Hof speak, you know he treats breathing as the gateway to seemingly inhuman feats.

But why the cold? As Carney argues, humans were, for a very long time, adapted to their environments. Automation and industry have changed that. We generally no longer need to kill or grow our food, build our own shelter, or flee from predators. Our tightly wound energy for physiological responses sits dormant. Exercising is one release, though the ways we often exercise—repetitive movements on machines—does not honor our diverse physiological ancestry. Our ability to survive in non-climate controlled environments fending for ourselves has been negated.

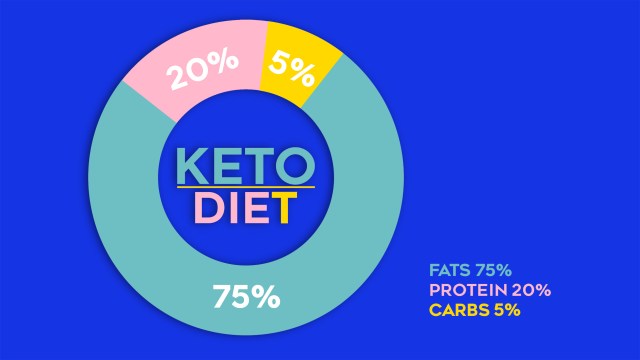

One key to surviving in extreme environments is the accumulation of brown fat, or so Hof espouses. Brown adipose tissue is different than its white counterpart. Specifically, brown fat’s main role is thermoregulation. It helps us shiver. The more we have of it, the sentiment goes, the more adapted we are to colder environments.

Not so fast, says a new study in The Journal of Physiology. Two groups of mice were exposed to cold climates. One group was put on a voluntarily wheel jogging regimen for twelve days before exposure; the other was comprised of couch mice. The exercising group fared much better. Their muscles were better suited to longer bouts of shivering.

Shivering is one of the first defences against cold, and as skeletal muscle fatigues there is an increased reliance on non‐shivering thermogenesis. Brown and beige adipose tissues are the primary thermogenic tissues regulating this process. Exercise has also been shown to increase the thermogenic capacity of subcutaneous white adipose tissue.

Photo: Shutterstock

Interestingly, how much brown fat each mouse had was not a factor. This doesn’t mean Hof is entirely wrong, however. In general, no mammal has an excess of brown fat, and it declines as we age. Hof’s argument is that we can build it through practices, such as his method. But movement seems to be a necessary key to this process of thermoregulation. As Discover reports on Hof’s ideas,

A crucial part of his “method,” however, also seems to be exercise, and as this most recent research indicates, being fit is probably another big boost to our bodies’ furnaces.

As the article notes, the researchers from the University of Guelph and University of Copenhagen did not measure the mice’s muscles while they were enduring 40-degree temperatures, so the link between exercise and thermoregulation is not completely solid. That said, they exhibited longer shivering bouts, meaning they were better adapted to the cold. Or, as the researchers conclude,

We speculate that prior exercise training could potentially enhance the capacity for muscle‐based thermogenesis.

But really, is it any surprise that exercise increases the likelihood we’ll survive in challenging environments?

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.