How the Keto diet—even without exercise—slays the opposition

Myths die hard—especially bad ones, it seems. In the last few months I’ve attended fitness classes in which the instructor told us that if we finish the upcoming workout, we’re allowed to eat whatever we want that night; that this class will take care of the holiday weekend; that this exercise will eradicate flabby arms and tummies. Some were expressed jokingly, yet the verbiage still points to an overarching misunderstanding about our bodies: that exercise cures the ravages of bad dietary habits.

This is especially true in terms of obesity. There are very fit people who appear to be carrying a few extra pounds, while there are tons of trim people who are hardly healthy at all. Weight is generally a terrible marker for fitness—no excuse for not staying in shape, however. Humans are biologically designed for movement. When we don’t meet a basic threshold, we suffer.

How exercise and nutrition fit into the jigsaw puzzle called health is debatable. I’ve heard it expressed as 75 percent nutrition, 25 percent exercise, a vague statistic I’ve used myself when students ask my opinion. It’s not necessarily a precise number, but it does give more weight to the food side, which is the point. My forty-five minute kettlebell class is not going to “erase” the pizza and six-pack you consumed last night.

Which is why researchers need to better understand ratios, such as an upcoming study—’Induced and Controlled Dietary Ketosis as a Regulator of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Pathologies’—to be pushed in the journal, Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. The results are fascinating.

Ketogenic diets are all the rage right now. The onslaught of ketone-fueled protein powders and exogenous ketones has begun, which might prove to be more marketing hype than credible science. (Nutritional ketosis is the gold standard. Pills and powder might help jumpstart the process, but they are no excuse for overloading on carbs.)

Taking advantage of our evolving knowledge of carbohydrate restriction, the research team, led by Madeline Gibas, an assistant professor at Bethel University focused on Human Bioenergetics and Applied Health Science, wanted to know if a ketogenic diet with no exercise was more beneficial to diabetics and sufferers of metabolic syndrome than the standard American diet with exercise.

Three groups were assembled, comprised of women and men between the ages of 18 and 65. All had previously been diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, pre-diabetes, or Type II diabetes. Their body mass index (BMI) was greater than or equal to 25 (or waist circumference above 37 for men and 31.5 for women) and body fat percentage above 30 percent.

Participants were randomly assigned to three groups, in the order they signed up for the study. For ten weeks the first group consumed a diet of less than 30 grams of carbohydrates per day and did not exercise; the second ate their normal diet and also did not exercise; the third ate their normal diet but exercised for three to five days per week for 30 minutes a session.

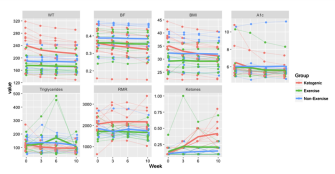

Gibas and her research partner, Kelly J. Gibas, Doctor of Clinical Behavior Sciences at Bristlecone Behavior Health in Maple Grove, Minnesota, focused on five biomarkers of metabolic syndrome, including “elevated triglycerides with excess muscle fat accumulation (IMTG), impaired maximal aerobic capacity (VO2), declined resting metabolic rate (RMR) and elevated body mass index (BMI) along with elevated hemoglobin.”

After ten weeks the data were clear:

The results show that while ample evidence indicates that exercise is beneficial, unlike a sustained ketogenic diet it did not have the ability to significantly alter the metabolic imbalance that accompanies metabolic syndrome over the course of the ten-week study.

Following a ketogenic diet, even with no exercise, proved statistically significant for weight, body fat percentage, BMI, A1C (glycated hemoglobin), and ketones. Some of the results were dramatic:

The resting metabolic rate in the ketogenic group also produced sizable change in the magnitude of the slope, more than ten times the other two groups.

The drastic influx of carbohydrates and sugar in the American diet has created innumerable physical and mental diseases that are easily prevented when an addiction to certain foods is curbed. We know overcoming any addiction is challenging, but until the medical industry treats our obesity epidemic as such, we’re unlikely to make major advances.

So it remains the work of researchers like the Gibases to present such data. In their study they point to 2015 research from 26 MDs and PhDs explaining our evolved awareness of nutrition, facts that still have not been implemented in many doctors’ offices around the nation:

1. Carbohydrate restriction has the greatest impact on decreasing blood glucose levels.

2. The benefits of carbohydrate restriction do not require weight loss.

3. Dietary total and saturated fat do not correlate with risk for cardiovascular disease.

4. Dietary carbohydrate restriction is the most effective method (other than starvation) of reducing serum triglycerides and increasing HDL.

Carbohydrate restriction—often in combination with fasting, though the science on how long is up for debate—is a non-pharmaceutical response that could help alter the fact that some 70 percent of our national medical costs could be avoided through better diet. (And yes, exercise does matter.) As the authors conclude:

Physiological ketosis has clinical utility for prevention, reduction and reversal of metabolic syndrome and its progression into obesity, pre-diabetes and diabetes and is therefore a noteworthy modality of alternative care.

—

Derek is the author of Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles, he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.