Chronic back pain: Novel mind-body treatment outperforms other therapies

- Chronic back pain is the leading cause of disability in the world, yet the condition often lacks clear causes.

- A recent study examined the efficacy of a novel treatment that frames chronic back pain as a condition rooted in psychological stress.

- The results showed that roughly 60 percent of participants who underwent the novel treatment had no pain six months after the experiment ended.

It is hard to overstate the damage and prevalence of chronic back pain. As the leading cause of disability worldwide, the condition affects about eight percent of U.S. adults, and each year it accounts for more than 80 million lost workdays and $12 billion in healthcare costs. The origins of chronic back pain are sometimes obvious: injury, poor posture, or certain genetic disorders.

But many cases lack clear causes. A 1946 study of American war veterans suffering chronic back pain was among the first to propose a rather surprising culprit for these mysterious cases: anxiety. The study suggested that chronic back pain is not necessarily caused by injuries or unhealthy movements in the physical world but rather can emerge from psychological distress. “Backaches caused by muscular tension improve when the anxiety state is relieved by psychiatric treatment,” the study noted.

A paper recently published in the journal PAIN Reports explored the efficacy of a novel treatment for chronic back pain, one that also frames the condition as rooted primarily in psychology. Although it is not the first mind-body treatment for back pain, the results suggest it could be the most effective.

A psychophysiologic approach to treating back pain

The study involved 35 participants, all suffering from chronic back pain that was not caused by an obvious injury. The participants were randomly divided into three groups.

One was directed to seek guidance from their regular physicians. Another group was assigned to undergo mindfulness-based stress reduction (MSBR), a meditation-based therapy that aims to help people improve the ways that they psychologically process stressors. The third group was assigned to undergo the novel therapy: psychophysiologic symptom relief therapy (PSRT). (Psychophysiology is a branch of physiology that examines the relationship between mental and physical processes.) The researchers described their new therapy as:

“…based on the hypothesis that nonspecific back pain is the symptomatic manifestation of a psychophysiological process that is substantively driven by stress, negative emotions, and other psychological processes. This intervention addresses underlying stressors and psychological contributors to persistent pain (including underlying stressful conflicts and aversive affective states), as well as conditioned pain responses and fear-avoidant behaviors.”

A longstanding body of research supports this psychosomatic hypothesis, showing that people who suffer from chronic back pain tend also to suffer higher levels of psychological distress, including feelings of sadness, anger, and anxiety. It is hard to determine whether back pain causes psychological distress or vice versa.

But what is clear is that suffering from back pain and psychological distress simultaneously can exacerbate both problems. A 2019 systematic review noted that people with chronic low back pain and depression are more likely to experience “higher pain intensity, greater disability, and poorer quality of life,” while also suffering worse treatment outcomes.

Psychological treatment for chronic back pain relief

The PSRT treatment played out over 12 weeks. The first four weeks of the program involved the participants learning about a psychophysiological model of pain developed by the late John Sarno, a professor of rehabilitation medicine at the New York University School of Medicine. Sarno’s key hypothesis was that chronic stress can cause chronic pain. He believed the way to treat chronic pain was to treat the underlying psychological issues, such as repressed emotions.

In small-group sessions, the participants read books about chronic pain and held discussions with physicians and mind-body experts. The goal was to illuminate the connections between stress and pain and to help people break them.

“As participants are encouraged to examine the origin of the pain, they notice patterns in the experience of their pain that reflect the contribution of psychological and stress-related factors (e.g. experiencing severe back pain when driving but only when in heavy traffic, pain that occurs with sitting but not when sitting on a chairlift during recreational skiing, pain that is worse while walking into the workplace but fine when walking upon exiting),” the researchers noted.

“Hereby, participants gain awareness of the connection between pain and psychological processes and a better understanding of the variety of potentially modifiable factors that contribute to chronic back pain.”

In the second phase of the therapy, the participants spent eight weeks learning and practicing MSBR. All groups filled out pain questionnaires before the study began, during each treatment, and periodically for six months after their particular treatment ended.

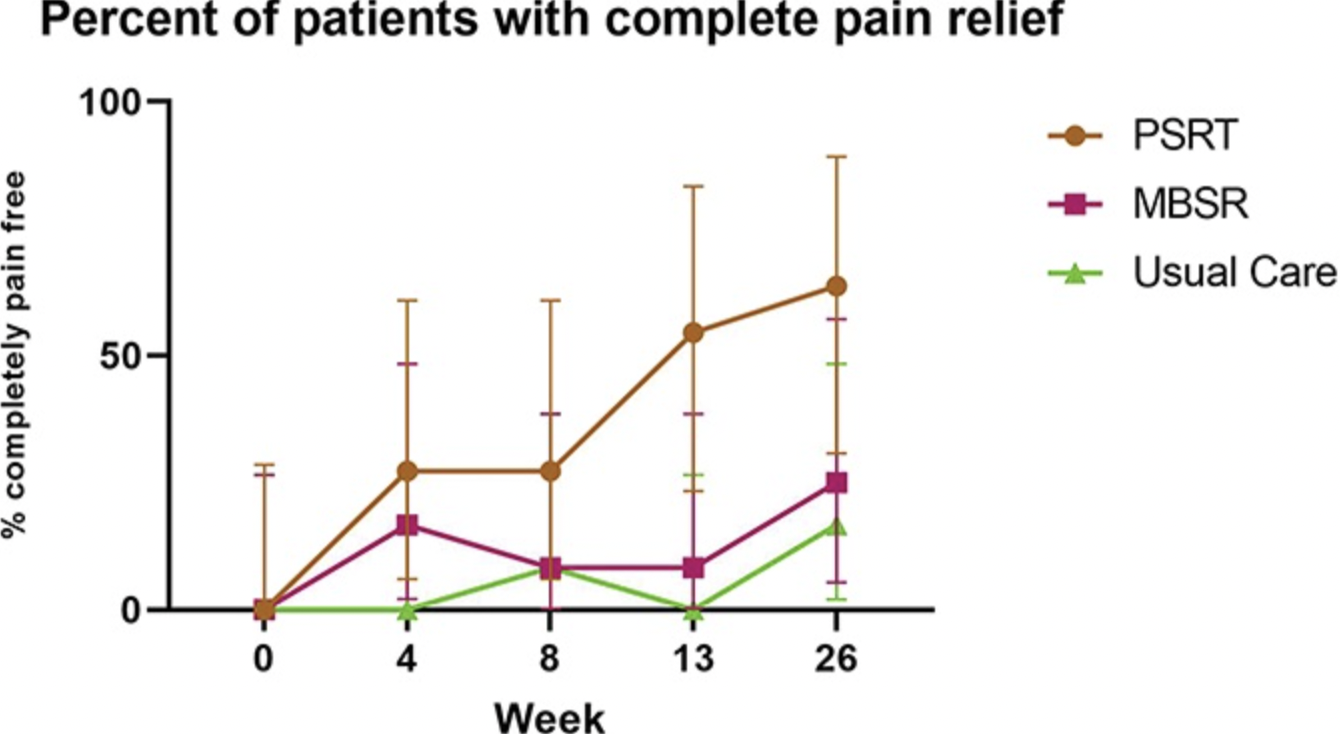

The PSRT group showed the greatest improvements by far. After four weeks, the PSRT participants reported an 83 percent reduction in pain disability, compared to 22 percent from the MSBR group and 11 percent from those who received usual care. In terms of pain bothersomeness, the PSRT group showed a 60 percent improvement, compared to 8 percent for MSBR and 18 percent for usual care.

These differences remained consistent over the long-term. After six months, 63 percent of participants in the PSRT group reported being completely pain-free, compared to 25 percent of the MSBR group and 16 percent of the usual care group. Still, the researchers noted that a larger randomized trial would bolster confidence in the efficacy of the treatment, which is not yet available to the general public.

The researchers concluded by highlighting the novelty of their approach.

“Mindfulness-based interventions aim to reduce pain through stress reduction and other multiple, unique neural mechanisms, irrespective of the etiology of the pain,” they wrote. “By contrast, PSRT acknowledges and treats pain as a manifestation of a psychosomatic or psychophysiological disorder. This subtle but fundamental difference provides patients with a much different orientation to their pain.”