Cracking a mystery about Vesta, our solar system’s second largest asteroid

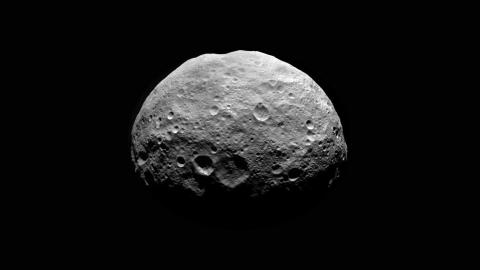

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UCLA / MPS / DLR / IDA

The asteroid Vesta is the second largest asteroid in the solar system’s asteroid belt, with a diameter of about 330 miles. (Ceres is the biggest.) It is the brightest asteroid up there, too, sometimes visible to the naked eye from Earth. Astronomers consider it a planetesimal because, like a mini-Earth, it has an iron core and rock in its crust and mantle.

The asteroid has long been an object of interest to star-gazers. The first book Isaac Asimov published was called Marooned off Vesta, and in 2011, the NASA spacecraft Dawn paid it a visit on its way to Ceres.

Dawn found two massive impact craters on Vesta — Rheasilvia and Veneneia — evidence of collisions large enough that they ejected about one percent of Vesta out into space. Indeed, roughly six percent of the meteorites we have found on Earth come from Vesta. Dawn also observed that there are two enormous troughs roughly around Rheasilvia and Veneneia. It has been assumed that they are somehow related to the two giant impacts.

A new study revisits this assumption and proposes a novel hypothesis about what exactly these mysterious troughs are.

Counting craters

If the troughs were produced by the Rheasilvia and Veneneia impacts, then they must be roughly the same age as the craters. Counting craters is one way to determine age.

“Our work used crater-counting methods to explore the relative age of the basins and troughs,” says co-author Jupiter Cheng. Since a newly formed body is free of impact craters, one can estimate its age by counting the number of craters present. While this is obviously an imprecise way of figuring out the absolute age of an asteroid, it is useful for determining the relative age of specific features. If the features are surrounded by a similar number of impacts, they are probably roughly the same age.

“Our result,” says Cheng, “shows that the troughs and basins have a similar number of the crater of various sizes [sic], indicating they share a similar age. However, the uncertainties associated with the crater counts allow for the troughs to have formed well after the impacts.”

This timeline fits with the researcher’s proposed explanation for the troughs.

Low gravity and the troughs

It has been assumed, says Cheng, that the “troughs are fault-bounded valleys with a distinct scarp on each side that together mark the down-drop (sliding) of a block of rock.”

However, there is a problem with this theory. It is based on the way rocks and debris behave under the force of gravity on Earth; Vesta’s gravitational pull is far less. Indeed, Dawn found Vesta’s gravity consistent with an iron core having a 140-mile diameter; the Earth’s, by comparison, is about 2,165 miles in diameter.

Cheng notes that “rock can also crack apart and form such troughs, an origin that has not been considered before. Our calculations also show that Vesta’s gravity is not enough to induce surrounding stresses favorable for sliding to occur at shallow depths. Instead, the physics shows that rocks there are favored to crack apart.”

Cheng summarizes, “Taken all together, the overall project provides alternatives to the previously proposed trough origin and geological history of Vesta, results that are also important for understanding similar landforms on other small planetary bodies elsewhere in the solar system.”

So while still consistent with the prevailing theory that the impacts resulted in the troughs, the researchers suggest that they did not cause landslides on Vesta. The impacts cracked it.