Your ‘big break’ can happen at any point of your career, Boston researchers say

Scientists can have their big break any point in their career. A paper published in the journal Science in 2016 determined that from a big data analysis on scientific careers from 1893 to 2010.

The research team, led by Roberta Sinatra and Albert-László Barabási of Northeastern University, determined that a scientist can make a lasting impact with their research from the very first published paper to the very last. There is no definite trajectory for success, and every successful scientist’s career is a mix of skill, persistence, and luck.

The research team figured all that out by analyzing publication information from scientists who published papers between 1893 to 2010. Those data points began with 236,884 physicist publications and expanded to 24,630 Google Scholar profiles and 514,896 publications across seven scientific disciplines “from physics to chemistry, economics to cognitive science,” according to the Northeastern press release.

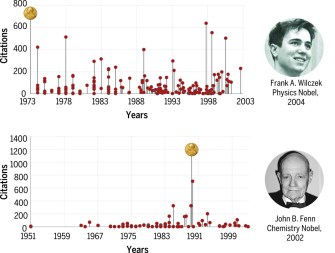

They crunched all of that data and came up with a productivity quotient or “Q.” “The Q factor captures a combination of ability, education, and knowledge… how good is a scientist at picking an idea and turning it into a discovery,” Barabási explains in the press release. “A high Q combined with continued efforts provide a forecast of what’s to come. We cannot predict when a big hit will come, but by examining Q — a stable factor — we can predict that one will likely come in the future,” Sinatra adds later. Here’s an example of what that might look like:

The probability of a scientist’s first paper being enormously impactful is exactly the same as their last paper being enormously impactful. As the study authors write, “We find that the highest-impact work in a scientist’s career is randomly distributed within her body of work. That is, the highest-impact work can be, with the same probability, anywhere in the sequence of papers published by a scientist.” That probability remains regardless of discipline, career length, “working in different decades, and publishing solo or with teams and whether credit is assigned uniformly or unevenly among collaborators,” according to the study.

“The composition of this Q quality, whatever you call it, is likely to vary in different fields,” Dr. Dean Simonton of the University of California, Davis told The New York Times about the Northeastern study. “That’s why you can see people who are highly successful in one field switch careers and not do so well.”

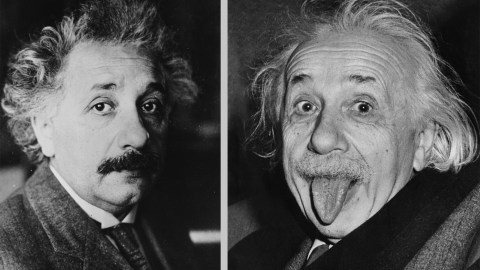

The biggest factor for success? “Productivity and the will to keep trying that corresponds with great discoveries, whether the scientist is 20, 40, or even 70,” explains Northeastern. “What matters is not the timing of discoveries that could affect future generations but that they happened… understanding that good scientists, if they have the resources to stay productive, could generate future big discoveries, independent of age, is essential for us to move forward in thinking about how to boost science.”

And if they can do it, you can, too.

The scientists are essentially cultivating the habit of “deliberate practice,” or pushing yourself slightly beyond your skill level. By utilizing deliberate practice every time you want to get better at something — from building a business to learning a language to writing that novel for NaNoWriMo — you increase your skill levels. You will most likely fail, but you’ll learn how to overcome that obstacle and push past it next time. That creates an atmosphere for success, as author David Shenk told us:

So remember: the next time you want to succeed at something, keep trying. Or, as Barabási put it for The Times, “The bottom line is: Brother, never give up. When you give up, that’s when your creativity ends.”