Why so gassy? Mysterious methane detected on Saturn’s moon

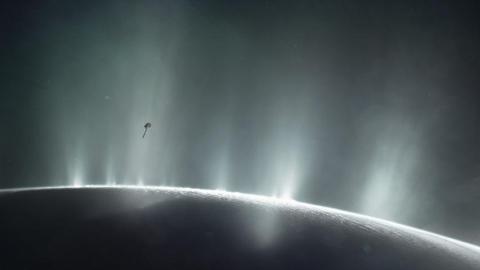

Credit: NASA

- A new study looked to understand the source of methane on Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

- The scientists used computer models with data from the Cassini spacecraft.

- The explanation could lie in alien organisms or non-biological processes.

Something is producing an overabundance of methane in the ocean hidden under the ice of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. A new study analyzed if the source could be an alien life form or some other explanation.

The study, published in Nature Astronomy, was carried out by scientists at the University of Arizona and Paris Sciences & Lettres University, who looked at composition data from the water plumes erupting on Enceladus.

The particular chemistry, discovered by the Cassini spacecraft which flew through the plumes, suggested a high concentration of molecules that have been linked to hydrothermal vents on the bottom of Earth’s oceans. Such vents are potential cradles of life on Earth, according to previous studies. The data from Cassini, which has been studying Saturn after entering its orbit in 2004, revealed the presence of molecular hydrogen (dihydrogen), methane, and carbon dioxide, with the amount of methane presenting a particular interest to the scientists.

“We wanted to know: Could Earthlike microbes that ‘eat’ the dihydrogen and produce methane explain the surprisingly large amount of methane detected by Cassini?” shared one of the study’s lead authors Régis Ferrière, an associate professor in the department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Arizona.

Earth’s hydrothermal vents feature microorganisms that use dihydrogen for energy, creating methane from carbon dioxide via the process of methanogenesis.

Searching for such microorganisms known as methanogens on the seafloor of Enceladus is not yet feasible. Likely, it would require very sophisticated deep diving operations that will be the objective of future missions.

So, Ferrière’s team took a more available approach to pinpointing the origins of the methane, creating mathematical models that attempted to explain the Cassini data. They wanted to calculate the likelihood that particular processes were responsible for producing the amount of methane observed. For example, is the methane more likely the result of biological or non-biological processes?

They found that the data from Cassini was consistent with either microbial activity at hydrothermal vents or processes that have nothing to do with life but could be quite different from what happens on Earth. Intriguingly, models that didn’t involve biological entities didn’t seem to produce enough of the gas.

“Obviously, we are not concluding that life exists in Enceladus’ ocean,” Ferrière stated. “Rather, we wanted to understand how likely it would be that Enceladus’ hydrothermal vents could be habitable to Earthlike microorganisms. Very likely, the Cassini data tell us, according to our models.”

Still, the scientists think future missions are necessary to either prove or discard the “life hypothesis.” One explanation for the methane that does not involve biological organisms is that the gas is the result of a chemical breakdown of primordial organic matter within Enceladus’ core. This matter could have become a part of Saturn’s moon from comets rich in organic materials.