When Netflix Is Attacked at Cannes, Will Smith Steps Up

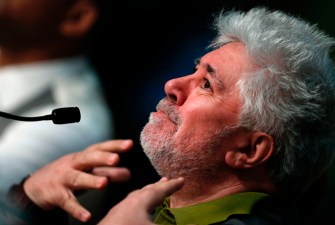

Two of the films in competition at this year’s prestigious Cannes Film Festival were produced by and for Netflix. It may be a watershed moment for films, given that the two movies — Okja and The Meyerowitz Stories — were produced for a TV streaming service, and not for a movie theater. At the festival’s opening press conference on May 17, renowned Spanish filmmaker and Palme d’Or prize juror Pedro Almodovar read a pre-written statement that said in part, “I personally do not conceive, not only the Palme d’Or, any other prize being given to a film and not being able to see this film on a big screen.”

Pedro Almodovar (Laurent Emmanuel)

When Will Smith raised his voice in defense of Netflix a while later, a conversation began that reflects a seismic shift — and for some, a sobering one — in the film industry. Almodovar and Smith were each no doubt reflecting the views of many other people.

Almodovar and Smith (Anne-Chirstine Poujoulat)

Prior to Almodovar’s statement, the mood at the press conference had been completely different. Though Cannes is always the place to see movie stars, few these days have the sheer wattage and charm of Will Smith, who had the room wrapped in the palm of his hand. “West Philadelphia is a long way from Cannes,” the star said, noting that, “I was probably 14 years old the last time I watched three movies in one day. Three movies a day is a lot!” Such is the lot of the Cannes festival juror. He also joked that he’d be trying to set a record for most outfits worn at the festival, 32, to top last year’s juror Kirsten Dunst’s 28.

Smith and crowd crush (Loic Venance)

Almodovar claimed his stance doesn’t come from being anti-technology, saying, “All this doesn’t mean I’m not open to or don’t celebrate the new technologies. I do.” And yet another statement of his suggests otherwise. “I’ll be fighting for one thing that I’m afraid the new generation is not aware of. It’s the capacity of the hypnosis of the large screen for the viewer,” the filmmaker says. “The size [of the screen] should not be smaller than the chair on which you’re sitting. It should not be part of your everyday setting. You must feel small and humble in front of the image that’s here.” Has he not seen the gargantuan TV screens on which people watch TV these days? Not even going into the home sound systems that support them.

Time and Change

It’s a simple fact of life that things change, and one has to feel for someone who’s devoted his or her life to an art form in which the public loses interest. Hand-drawn animators spring immediately to mind, as do classical and jazz musicians (actually, musician’s of any style that becomes passé). The passing of the white-hot spotlight from one form to another does not in any way diminish the real value of the one left in darkness, but it painful to feel an audience’s attention moving on. And it’s not that, for example, there isn’t still hand-drawn animation being produced. It’s just harder to find. And there will likely always long be movie theaters showing films. They may just not be everywhere.

Bowling for Dollars

Of course, with an audience moving on, so goes the money required to produce a film, and in this regard, Almodovar’s position makes practical sense. But not entirely. Studios chase the massive jolts of income they can derive from hit movies, and that’s a business call having nothing to do with Netflix. The rise of original content on streaming services isn’t the cause of the financing issues of smaller films. And according to theStephen Follows website, producing $100m+ movies requires deep pockets.

So, movies seen on big screens in a dark room account for only a portion of the money they stand to make. Of the roughly $423 million such a film makes on average, only $169 million comes from theatrical release, and the rest ($254 million) from other, smaller-screen venues.

Access Hollywood

Will Smith (Laurent Emmanuel)

Smith’s defense of Netflix at Cannes referred to the access it provides audiences to otherwise unavailable films: “In my house, Netflix has been nothing but an absolute benefit. They get to see films they absolutely wouldn’t have seen. Netflix brings a great connectivity. There are movies that are not on a screen within 8,000 miles of them. They get to find those artists.”

If that’s so for kids living in L.A., imagine what a service like Netflix is doing for those not living in urban or suburban areas with multiple theaters. About 18% of Americans live in rural areas where they’re lucky to have even a single theater, and that would be a theater showing only “tentpole” movies starring, well, Will Smith. Just one example of a director whose films never appear in say, Houghton, Michigan would be Pedro Almodovar, Netflix or not. Netflix — either via DVD or streaming service — is the only way many people can see non-blockbuster films.

There’s another issue that gives Almodovar’s position a whiff of elitism. Going to a theater is expensive, even if you don’t buy popcorn and a drink. The average movie ticket price in the U.S these days for an evening show is $8.64. For a family, that’s a tab that starts at $25.92. A month of Netflix is $7.99 to $11.99 by comparison, and you can watch as many movies as you want.

Where Do You See Film?

For many who do have access to movies in a theater or on their TV, the decision involves a personal calculus that depends on how much they enjoy watching a movie in a theater or at home. In a theater, there’s that huge screen and sound system, but there’s also the cost, people talking through the film, phones going off, and sticky floors. At home, you’ve already paid, and you needn’t get dressed, you can watch whenever you want, you can rewind, and your home entertainment system probably doesn’t look and sound too shabby. On the other hand, it’s a more solitary experience, life has a way of interrupting movies, and the screen is still smaller than movie theater’s.