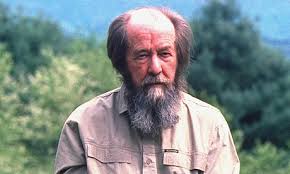

Solzhenitsyn and the One True Progress

Judging from their mid-term essays, I would say that among the many and diverse books and essays we’ve read so far in my course in technology, the one that has impressed the students the most is the Russian anti-communist dissident and writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “We Have Ceaser to See the Purpose,” an address given to the International Academy of Philosophy in Liechtenstein in 1993. I have not been able to find the text conveniently linkable online. It can be found in The Solzhenitsyn Reader, edited by Mahoney and Ericson (ISI Books).

Let me give you some especially provocative quotes:

1. “It is up to us to stop seeing [technological] Progress (which cannot be stopped by anyone or anything) as a stream of unlimited blessings, and rather view it as a gift from on high, sent down for an extremely intricate trial of free will.” Quick takeaway: Technological progress is a gift, one made possible by capabilities for freedom members of our species alone have been given. It’s not a gift for a life full of unlimited freedom and enjoyment. It’s a tough and complicated moral challenge. Can we use our “free will” to subordinate our unprecedented techno-freedom to properly human purposes and concerns? We won’t be able to feel good without being good. More than ever, we’ll have to be good—to practice virtuous “self-limitation”—to live well, to be happy. Those who believe that techno-progress can be stopped, that we can simply choose to avoid this new trial, are wrong.

2. “And nothing so bespeaks the current helplessness of our spirit, our intellectual disarray, as the loss of a clear and calm attitude toward death….” Although we don’t talk much about death, we’re more death-haunted than ever. Solzhenitsyn hears “the howl of existentialism” rising; “life has become a harrowing prospect indeed.” Nothing makes us more dazed and confused—more in the thrall of diversion and self-denial—than being unable to live well with death.

3. “Man…began to deem himself the center of his surroundings, adapting not himself to the world but the world to himself. And, then, of course, the thought of death becomes unbearable: It is the extinction of an entire universe at a stroke.” The end of ME is the end of being itself. No Darwinian, of course, could think that, and no Christian either. That all of being centers around me is the purely techno-view; making my surroundings more all about me is the only change I can believe in. If “the thought of death is unberaable,” then we really can’t think much at all about who we are and what we’re supposed to do.

4. “The gift of heightened life expectancy has, as one of its consequences, made the elder generation into a burden for its children, while dooming the former to a lingering loneliness, to abandonment in old age by loved ones, and to an irreparable rift from the joy of passing on their experience to the young.” Living longer is a good for which we should be grateful. But it has its costs, especially for the old. Being a lonely, relatively joyless, abandoned burden is better than be being dead. It really is, though, a huge trial for free will. And the rest of us (well, the rest of you) must find the virtue to do what you can to repair relational virtue enough not to abandon—to, in fact, love—those who really do tend to be most deprived of purpose in the techno-world filled with preferential options for the young. If you think about it, more than ever you need the experience of the old to be passed on to you.

5. “There can be only one true Progress: the sum total of the spiritual progresses of individuals; the degree of self-perfection in the course of their lives.” The only real Progress is personal, and the only really Progressive society is full of individuals who have devoted themselves to the pursuit of self-perfection through self-limitation in the service of a spiritual purpose higher than comfort and material enjoyment. The truly Progressive focus should always be the predicament of the free but limited being born to love and die.

There’s a lot more, of course.