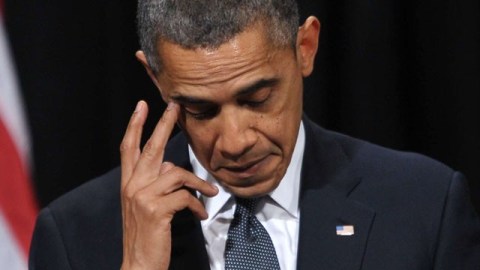

Does Obama Really Want to Strike Assad?

“I’m not itching for military action.”

— Barack Obama (Friday, September 6)

I feel for Obama. The 43rd president has had his share of crises to handle in the first four and and half years in office, but the decision on what to do with regard to Syria is probably his diciest. There are no costless options on the table. Allowing Assad to deploy chemical weapons “with impunity” may invite the Syrian dictator to use more nerve gas on his people. It may embolden other countries unfriendly to the United States to develop and use weapons of mass destruction. But punishing this breach of an international norm is no guarantee that Assad will politely agree to lay down chemical weapons in the future. And there is no reason to expect that launching a few cruise missiles at Syria will scare Iran away from its nuclear program, especially given the slow and irresolute manner in which only a handful of countries have tiptoed up to support a possible, “limited” and “proportionate” strike.

The administration and supporters of military action have been speaking piously about “the risks of inaction” and warning that “sitting on our hands” is dangerous to the security of the country. Fair enough. Yet many potential outcomes of military intervention are highly risky as well. Ezra Klein listed ten dark scenarios earlier this week. Here they are, in brief:

1) Our strikes could result in heavy civilian casualties.

2) Our strikes could result in Assad killing more civilians.

3) Our strikes could result in Assad killing more civilians with chemical weapons.

4) The attacks are so slight that Assad survives them easily and appears strengthened before the world.

5) “You bombed it, you own it.”

6) Reprisal.

7) Assad falls and the chemical weapons end up in the wrong hands.

8) Assad falls and is replaced by chaos.

9) Assad falls and is replaced by something worse.

10) Escalation.

These risks of military action are significant, and the consequences of items 1 through 6 would come pretty quickly. Items 7-9 are essentially alternate bad outcomes if the best-case scenario — the fall of Assad — comes to fruition. Given recent horrors in Egyptand given known Syrian rebel ties to al-Qaeda, it would be rather surprising if a post-Assad regime in Syria would represent a beacon of peace and democracy.

The risks of inaction, by contrast, sound less immediate and more manageable. This seems to be the dominant view among members of the American public, and it appears, for now, to be the controlling opinion among members of Congress.

What, then, will Obama do? If he does not get the support of Congress, I doubt he will send missiles into Syria. If he does get the Senate and House of Representatives to approve the resolution, he will likely pursue a limited strike. Yet gaining congressional support leaves one not-insignificant problem for the American president: the attack would fairly clearly be in violation of international law. Here is Jack Balkin, a Yale law professor, on the global rules of military engagement that are written into the United Nations charter:

There is no direct threat to American security, American personnel, or American interests. There is no Security Council resolution to enforce. And there is no claim that America needs to shore up the credibility of NATO or another important security alliance. Nor does Obama have even the feeble justification that the Clinton Administration offered in Kosovo: that congressional appropriations midway through the operation offered tacit and retroactive approval for the bombings….

When a member state is not defending itself against attack, the charter generally permits the use of force only when authorized by a Security Council resolution. And there has been no such authorization in the case of Syria.

The whole point of the charter is to prevent member states from attacking each other based on their individual interpretations of international law. If Russia or China decided to attack an American ally on the grounds that it had violated international law, the United States would surely object, and rightly so. Even if America’s goal is humanitarian intervention with the purest of motives, it would be legal under the charter only if the Security Council determined that humanitarian intervention was justified. What Obama is proposing to do is precisely what the charter was designed to prevent.

Obama the law professor knows all this. He is now trying to dial back his rather-clear-at-the-time declaration of a “red line” a year ago, and I’m sure he is kicking himself for making those statements without having a clear response in mind should Assad step over the line. The president’s ambivalence about a strike was evident in his comments yesterday:

“I was elected to end wars, not start them. I’ve spent the last four and a half years doing everything I can to reduce our reliance on military power as a means of meeting our international obligations and protecting the American people.”

This is Obama in his heart of hearts. Feeling pressure to back up his ultimatum with American military might, he seems to feel the risks and limitations of a strike more heavily. Tossing any missiles will kill some innocents. Send too few and Assad will laugh; send too many, or send them off course, and many civilians will die. Obama says he wants Congress to approve the strikes, but he is rather cold and technocratic when making the case. It has been up to John Kerry and Joe Biden to deliver the impassioned speeches. Something tells me Obama might be secretly hoping Congress rejects his bid for military action.