This is What Our Nearest Exoplanet May Look Like – A Giant Eye Staring at the Sun

Donald Who? Centuries after this era’s headlines are forgotten, 2016 will be remembered as the year we discovered our ‘Planet B’.

Because even if we find a billion more Earth-like exoplanets, none will ever be closer to home than Proxima Centauri b, spotted circling our nearest star (1) on August 24th of last year. At a mere 4.25 light-years away, it is close enough for us to contemplate visiting, and perhaps even living there.

One of the few things we know about Proxima b, besides that it is a rocky planet with a mass 1.3 times that of Earth, is that its orbit is in the so-called ‘Goldilocks zone’ of its sun: not too hot nor too cold for liquid water, making it a potential host for life – alien, human or both.

So what does this ‘Earth Next Door’ look like? We don’t really know. Planet B has only been observed indirectly, via Doppler spectography. If we sent a spacecraft there tomorrow, it would take decades for it to get there and send home pictures.

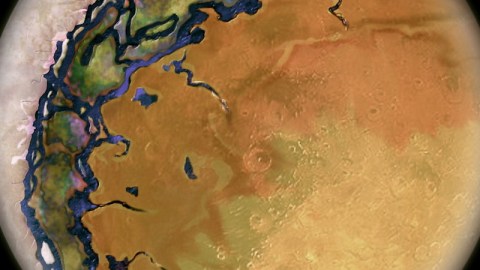

But we can speculate. And this is what Proxima B could very well look like: an ‘Eyeball Earth’.

Eyeball Earth: it sounds weird and it is weird. Tidally locked with its sun, an Eyeball Earth consists of three extreme climatic zones – scorchingly hot on the permanent day side, icy cold on the permanent night side. In between, ringing the planet: a thin, potentially habitable strip.

This setup gives the planet the appearance of an eyeball. Permanently staring into the sun.

The concept of an Eyeball Earth was kicked off by the discovery in 2010 of Gliese 581g, in the Goldilocks zone of its parent star, a red dwarf. Scientists speculated this planet type, occurring around red dwarfs, would be the likeliest candidate for life to evolve on.

Red dwarfs, a.k.a. M stars, make up around 75% of the stars in our galaxy. They are smaller and dimmer than our own sun, so their Goldilocks zone is much closer by than in our case (our sun is a yellow dwarf). Hence the tidal lock (2).

A year on Proxima b only lasts 11.2 Earth days. That’s how long the planet takes to revolve around its sun – our nearest star Proxima Centauri, a red dwarf about one-seventh the diameter of our sun, and one-eighth the mass. The planet’s distance from its sun is only 7.5 million km, or 1/20th of the Earth’s orbit around the sun. So our Planet B could very well be an Eyeball Earth.

But will we really have to get there to be sure? Some scientists hope that the James Webb Space Telescope, to be launched in 2018, will be able to deliver some answers. Whether it is in fact tidally locked with its sun, for example. And, crucially, whether it has an atmosphere. If so, life is possible – in that ‘ring of habitability’, between the planet’s hot and cold halves, their extremes mitigated by the atmosphere’s redistribution of heat. Without an atmosphere, Proxima b might be a lifeless rock after all.

Astronomers only started detecting exoplanets – i.e. planets outside our own solar system – in the 1990s. By now, they’ve identified as many as 3,000, plus another 2,500 possible ones. In 2013, it was estimated there could be about one billion ‘Earths’ in our galaxy. If the presence of Proxima b at our nearest star is an indication of their prevalence – i.e. at least one around each star – we could be looking at as many as 500 billion ‘Earths’ in our galaxy.

That’s a lot of eyeballs. Next time you’re under the stars at night, looking up at the Milky Way, just think of all those stares in your direction. Perhaps even literally. Who knows, in that habitable strip on Proxima b, somebody might be aiming a telescope at us, to check whether our rock has an atmosphere.

Image by Beau.TheConsortium, found here on Space.com.

Strange Maps #801

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) A top ten of closest stars:

1Proxima Centauri (4.25 ly) – in the same star system as the next two.

2Alpha Centauri A (4.36 ly) – the main star in Centaurus, a constellation in the southern sky.

2Alpha Centauri B (4.36 ly) – slightly smaller and less luminous than both our sun and Centauri A.

4Barnard’s Star (5.96 ly) – the closest star in the Northern Hemisphere.

5Luhman 16A (6.59 ly) – the primary in a binary brown-dwarf constellation, discovered only in 2013.

5Luhman 16B (6.59 ly) – orbits its companion star at a distance of about 3 AU, with a period of about 25 years.

7WISE 0855−0714 (7.20 ly) – located in the constellation Hydra, its discovery was announced in 2014 by the people that also brought you #5.

8Wolf 359 (7.78 ly) – with a cool name like that, it’s no wonder this star crops up in lots of sci fi, from Terry Pratchett to Star Trek.

9Lalande 21185 (8.29 ly) – a red dwarf in the constellation Ursa Major.

10Sirius A (8.58 ly) – main star of a binary system that is the brightest object in the night sky

10Sirius B (8.58 ly) – a white dwarf much smaller than Sirius A, with which it is locked in a 50-year orbit.

(2) Like the Moon with the Earth, which is why we only ever see one side of our natural satellite. The Moon’s other side gets as much sunlight as the Earth-facing side. It is only ‘dark’ in the sense that is was unknown for so long (the Soviets had it mapped by 1960).