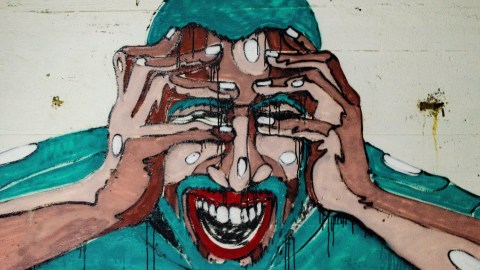

Psychologically and physically, traffic is terrible for our health

Photo credit: Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash

- Traffic has been implicated in measurable exhaustion, an increase in blood pressure, negative attitudinal shifts, and a constant release of stress hormones.

- In 2009, 3.9 billion gallons of fuel and 4.8 billion hours of time were wasted by Americans sitting in traffic.

- Traffic is costing the US economy $100 billion every year.

Shortly after moving to Santa Monica in 2011, I was scheduled to teach a class in West L.A. at 6 p.m. on a weekday. Leaving my apartment at 4:30, which was located two miles from the club, I planned on getting an hour workout in before class started.

I was wrong.

The only reason I was able to rush into the club by 6 p.m. was because I drove the wrong way down a one-way service road to cut in front of a few blocks of traffic. If that option hadn’t become available I was about to park and sprint the remaining blocks, under the bridge of the 405, the source of my disdain.

Ninety minutes to travel two miles might seem like an outlier in Los Angeles. While at the extreme end, it’s not unheard of. A former eight-mile commute never took less than an hour.

Before moving to L.A., I was warned about how often people talked about traffic. How you get around is woven into the fabric of the culture. In a city dominated by Instagram celebrities posting fad workouts and sponsored branded content to a population obsessed with fitness and healthy food, the irony is stark: traffic is terrible for our health.

The Californians: Stuart Has Cancer (Dress Rehearsal) – SNL

Yet it’s especially terrible in L.A.

As Austin Frakt writes in the NY Times, the average American sits in rush-hour traffic for forty-two hours a year. In this city that number is roughly double. The lost time and wasted fuel expenses cost the nation $100 billion every year — and that report is from 2010.

According to that mobility research, in 2009, 3.9 billion gallons of fuel were wasted, alongside 4.8 billion hours of time, because of traffic. Tesla and others are trying to solve the first part of that problem, but time lost is damaging to our psyches as well, according to the National Institutes of Health:

“Persons who lived in areas with greater vehicular burden and who reported the most traffic stress also had the lowest health status and greatest depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that traffic stress may represent an important factor that influences the well-being of urban populations, and that studies which examine factors at only one level (either individual level only or ecological level only) may underestimate the effect of the social environment.”

Environment matters. While I live on a relatively peaceful street, our bedroom faces Overland Avenue, a rather busy road. I’ve used a white noise machine to sleep for decades regardless of where I live; here it’s a necessity, the only way I can sleep. It’s not only sitting in traffic that’s dangerous to our health. The sounds it creates don’t help either.

Musician and naturalist Bernie Krause writes about the damaging effects of noise in his book, The Great Animal Orchestra. He points to disturbing data from a landmark study in the eighties measuring the effects of traffic noise on our nervous system. For two weeks, volunteers slept in uninterrupted quiet, their physiological baseline recorded.

For the following two weeks, they slept hearing traffic sounds. An expectable disturbance was recorded early on; the problem, Krause writes, is that even as the volunteers became accustomed to noise, their bodies were still being stressed. Low-level, persistent anxiety never disappeared:

The measured physiological stress levels were consistently as high as when the traffic sounds were first introduced.

Science shows just how bad sitting in traffic is for you

Living in areas of constant noise has numerous adverse effects, including fatigue and stress, marked by measurable exhaustion, an increase in blood pressure, negative attitudinal shifts, and a constant release of stress hormones, some of which play a role in cardiovascular problems. We’re tied into whatever environment we live in. As research continually shows, urban regions are not conducive to good health.

There’s even been a relationship between domestic violence and traffic in — you guessed it — Los Angeles. A 2018 study on the matter, published in the Journal of Public Economics, states:

“We find that extreme traffic increases the incidence of domestic violence, a crime shown to be affected by emotional cues, but not other crimes.”

Humans are responding in their own ways. In a gig economy where many people work remotely, the younger generation is driving less. Fewer cars are not great for the auto industry, yet it’s certainly a boon for the planet. Those people still need to get around, however, especially in a gig economy where many rely on the economic incentive of delivering food and other people. The idea that the problem will solve itself due to millennial habits is lofty at best.

Taking mobility services seriously isn’t only good policy, it’s necessary for public health. At least some legislators are recognizing this. Los Angeles transit agency, Metro, has announced a “Mobility on Demand” service, in which low income riders can share a car to public transportation destinations. And while Elon Musk made headlines last month as his first hole opened to the public, other LA residents shut down his dream of beachside expansion due to NUMBY—not under my backyard.

Car pooling, as with the Metro plan, is an incremental help, yet nowhere near what we need to combat the physiological stressors traffic wages on our bodies. Believing growth to be exponential is a byproduct of capitalism, not nature. The consequences of our creations simply aren’t worth the physiological and psychological damage they inflict.

A solution starts with self-reflection. A cheeky yet insightful post I once read nails the truth: You aren’t sitting in traffic, you are traffic. Only when we recognize that we’re each part of the problem will we begin to seriously consider appropriate courses of action. Until then, the podcast and satellite radio industries will continue to boom.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.