5 quotes from the “Tao Te Ching” to help bring balance to your life

- Finding a sense of harmony can be difficult when facing the struggles of modern life.

- The Tao Te Ching shows us that the search for balance has challenged people across cultures for thousands of years.

- Instead of struggling, the Tao Te Ching recommends we flow with these challenges and embrace the contrasts within us.

Sometimes it seems as though we are living through an era that’s perpetually off balance. Each day, the news brings us stories of conflict and political polarization. People search for, but can never find, that elusive work-life balance. And the challenges of modern living fill our lives with stress, burnout, and a never-ending time famine.

While it is true that the world can be volatile and life confusing, this perspective also misses a vital point: Whether as individuals or as a society, we have always struggled to find balance in our lives. Our time isn’t special in this regard; it’s been a constant human endeavor. That’s why thinkers across the ages and from disciplines such as religion, philosophy, and science have attempted to offer their own answers to help.

More than 2,000 years ago, during China’s Warring States period, one such book provided insightful, if often enigmatic, answers: the Tao Te Ching.

Nameless is the beginning

According to legend, in the sixth century B.C., Lao Tsu served as the keeper of the imperial archives. Witnessing the decay and corruption of his society, he resolved to leave it behind and ride into the western desert. When he reached the Hangu Pass gate, he met a guard named Yinxi. Yinxi instantly recognized Lao Tsu’s wisdom and begged the sage to help society by writing down his teachings. Thus, the Tao Te Ching was born.

Then again, maybe it was the fourth century B.C.? And did Yinxi meet him at the Hangu Pass or the western gate of the capital city? And when did Lao Tsu meet Confucius in person and earn his respect?

The truth is that scholars can say precious little about the origins of the Tao Te Ching and less about its author, Lao Tsu. Even his name, which translates literally to “Old Master,” is more an honorific than a designator that might indicate family ties, place of origin, and the like. As a result, the figure of the Old Master is something like a mirror: You see what you put in.

For religious Taoists, he is a divine figure who is thought to personify the Tao itself — that is, the unified order of the Universe. In philosophy, he is the central figure of one of the three main schools of thought that shaped Chinese culture and society and, by extension, those of East Asia. Meanwhile, many modern scholars argue that he is pure legend and not a historical figure at all.

Like its accredited author, the Tao Te Ching is a multifaceted maze of understanding. Separated into 81 pithy chapters composed in verse, the Tao is one of two fundamental scriptures of the Taoist religion (the other being the Zhuangzi). Its message is paradoxical, more than a little counterintuitive, and oftentimes self-contradictory. For some readers, these qualities express the complexity and nuance of the text. For others, they signal that it is not the work of a single thinker but a collection of oral proverbs circulating around the second half of the third century B.C.

“Paradox is the essence of the Tao Te Ching, so much so that even scholars with a solid grounding in classical Chinese cannot be sure they have grasped what the Old Master is really saying in his pithy maxims,” Victor Mair, a sinologist, notes in the afterword to his translation.

For such a short, terse work, its subject matter is also incredibly far-ranging. Depending on the chapter being quoted, it can be a political treatise on proper statecraft or a philosophical exploration of ethics. At other times, it acts as a metaphysical revelation, unveiling the underpinnings of the Universe and offering mystical insights. It can also serve as a guide for finding satisfaction in a life lived in simplicity.

The Tao Te Ching and the pursuit of balance

With that said, there does appear to be a through line connecting these various facets together — at least, as much of a through line as you’ll get with the Tao Te Ching. That is the importance of balance. Whether looking to the cosmic order, to society, or to ourselves, the text stresses the need to find balance and bring our pursuits in line with harmony.

Whether you are approaching the Tao Te Ching for his philosophy, its practical advice, or in a more spiritual sense, the need for balance is its pervading lesson in helping people find either their way or the Way.

Here are five verses to help guide you in finding that balance and that also serve as a primer to important concepts in the Tao Te Ching.

Chapter 8

The highest good is like water.

Water gives life to the ten thousand things and does not strive.

It flows in places people reject and so is like the Tao.

While yin and yang is perhaps the best known of Taoist symbols, water is the principle analogy of the Tao Te Ching. Water’s properties best encapsulate the otherwise ineffable Tao, and as such, Lao Tsu teaches his readers to act in accordance with water.

How does one do that? Consider how water behaves. As Mair notes, when it is appropriate, water can sit patiently in a pond, or it can flow as a stream. It’s non-confrontational. It makes room for everything that enters it and accommodates any situation by assuming a new shape. It is humble, always flowing down to the lowest level. Finally, it is yielding and reticent.

Those characteristics may seem like a call to be a wallflower, submit to others, and never assert yourself. But that’s not the case. As the Tao states in Chapter 78: “Under heaven nothing is more soft and yielding than water. / Yet for attacking the solid and strong, nothing is better; / It has no equal.” Stone represents people who are immovable, confrontational, and overly assertive, and while it may seem like the stronger of the two substances, it is water that carves canyons to ultimately find its way.

Note also how water’s characteristics aren’t just inwardly focused. Being humble, non-confrontational, and accommodating can help us build cooperative partnerships and meaningful relationships — and in doing so, help us achieve balance with the world as much as with ourselves.

Chapter 29

So sometimes things are ahead and sometimes they are behind;

Sometimes breathing is hard, sometimes it comes easily;

Sometimes there is strength, and sometimes weakness;

Sometimes one is up and sometimes down

Therefore the wise avoid extremes, excesses, and complacency.

Avoiding extremes and excesses is the very definition of balance. If we live a life of gluttony, we become unhealthy. If our diet is too strict, we become miserable. If we are always working, we’ll drain the joy and meaning from our lives. If we’re always lazing about, we miss out on the satisfaction of doing something well. You can no doubt think of many other examples.

None of this is to say that the search for balance is easy or that we’ll always be successful. As this verse suggests, we’ll sometimes find ourselves leaning toward one extreme or the other. The challenge then is to not grow complacent or give in to despair. Remember that difficult things will get easier one day; the easy road cannot continue forever. A person’s aim then shouldn’t be to conquer the moment and to force it to fit their desires. It should be to fulfill their purpose and flow with the moment.

Chapter 42

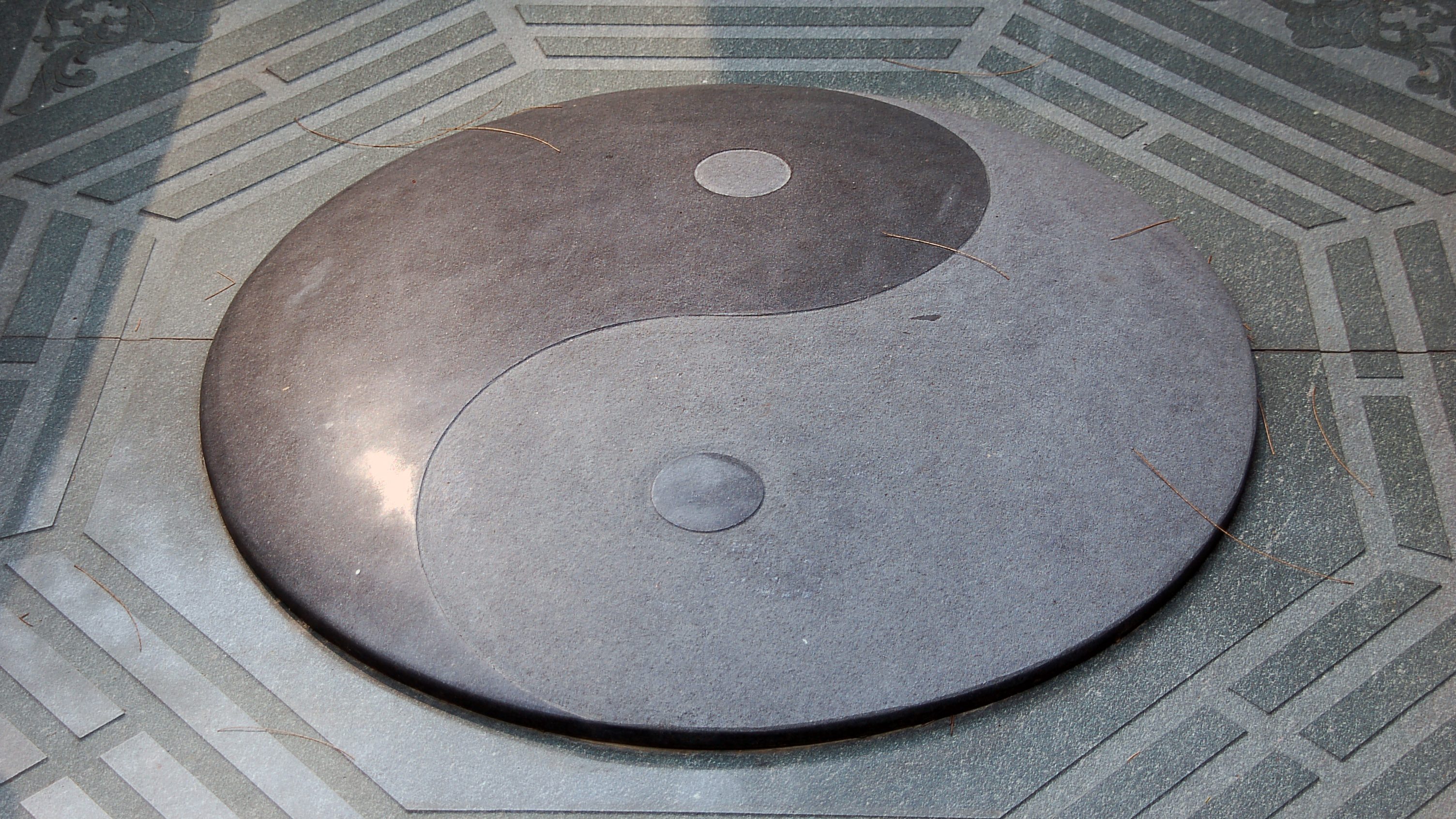

The ten thousand things carry yin and embrace yang.

They achieve harmony by combining these forces.

People hate to be “orphaned,” “widowed,” or “worthless,”

But this is how the wise describe themselves.

Despite its prominence in pop culture, yin and yang is only mentioned directly in this chapter. It is alluded to elsewhere — for example, Chapter 28 states: “Know the white, / But keep the black!” — but its rarity doesn’t speak toward its importance in the Tao Te Ching.

The “ten thousand things” is a literal translation of the Chinese wan-wu. Sometimes translated as the “myriad creatures,” the phrase refers to all the beings that exist in the Universe. From the book’s metaphysical perspective, all beings originate from and are nurtured by the Tao, which is both unified and without existence. Even the gods are part of the Tao. (If you return to Chapter 8, you can again see why water, which sustains life for the ten thousand things, is favored as a symbol of the Tao.)

Here, the point is that every person houses contrasts within them. We have our yin side and our yang side. Our masculine side and our feminine side. Our serious side and our playful side. Our rational side and our emotional side. And so on.

To find balance, we shouldn’t favor one side and ignore the other and neither should we pit these qualities against each other. They are a part of us, and we should accept and embrace them equally. That includes those qualities that we might find embarrassing and unacceptable. Such qualities don’t make us moral or immoral, worthy or unworthy. They just are.

This chapter ends with the teaching, “A violent person will die a violent death!” That seems like a rather extreme takeaway until you realize that the violence in question is the oppression of one quality over another. Whether that oppression is personal or social, translators Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English* write in their comments: “The wise do not seek to triumph in this way.”

Chapter 63

Practice non-action.

Work without doing.

Taste the tasteless.

Magnify the small, increase the few.

Reward bitterness with care.

See simplicity in the complicated.

Achieve greatness in small things.

“Non-action” is a translation of the Chinese wu-wei, and at first glance, it seems like another philosophical call to chill out, roll with the punches, and let the world pass you by. But here, translators bump up against the issue that wu-wei has no true English equivalent. In the Taoist sense, “non-action” doesn’t literally mean “no action.” Rather, it defines actions that are frictionless, non-interfering, and effortless.

There are many different ways to think about wu-wei. In traditional Taoism, it can be a laissez-faire political view or a genuine desire not to take part in human affairs. Leo Tolstoy’s anarcho-pacifism seems inspired by the concept, and Alan Watts views it as simply not forcing things.

“Wu-wei as ‘not forcing’ is what we mean by going with the grain, rolling with the punch, swimming with the current, trimming sails to the wind, taking the tide at its flood, and stooping to conquer,” Watts writes.

Today, we may view a type of wu-wei as flow state or being in the zone. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi outlined six key factors that compose flow state: sharp focus, mindfulness, a sense of control, an altered perception of time, intrinsic rewards, and the absence of second-guessing. In other words, it becomes “work without doing” because doing feels like your natural state within the moment.

To help you get in the zone, it helps to strip away complexities that interfere and distract. Instead, magnify the small by focusing on what’s the most important to the task at hand and that you can do well. Make those the small things that you can build upon.

Chapter 81

The wise never try to hold on to things.

The more you do for others, the more you have.

The more you give to others, the greater your abundance.

The Tao of heaven is sharp but does no harm.

The Tao of the wise is to work without effort.

As mentioned, the Tao Te Ching recognizes that humans are social creatures. We have a powerful instinct to congregate and work together. The better the people around us do — whether that’s our families, our workplaces, or society at large — the better we do.

As such, the Tao Te Ching teaches that the wise don’t try to hoard things or moments or achievements because it recognizes that these things have no value in and of themselves. It is only in relation to others that these things inherit value, and when we give or share them, we spread out their worth. That can be in the form of charity, assistance, social gatherings — you name it.

And modern research in positive psychology is catching up to the Tao’s centuries-old wisdom. Research has shown that prosocial behaviors boost our health and mental well-being. Even something as small as a random act of kindness or expression of gratitude flows out from the giver to make other people happier. Even if people aren’t the recipient of such generosity, simply witnessing can be a source of happiness, fulfillment, and awe.

“So is [giving] selfish or selfless? Well, it’s neither and both; it’s self-full,” psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar said in an interview. “Self-fullness synthesizes the best of both worlds, giving oneself and giving others. And they work together, reinforcing one another in an upward spiral of generosity and benevolence.”

Finding your Way

For all its paradoxical sayings, for all its mysticism and associated legend, the Tao Te Ching is also a remarkably practical book. Its advice is applicable to anyone searching to bring balance and harmony in their lives — which is anyone living in the last, say, 2,000 years. I think that goes a long way in explaining not only its continued influence on Chinese culture but also its proliferation around the world.

It’s also unique for works of its time in that it does not couch wisdom in ritual or providence or even a specific school of thought. Rather, the advice of the Tao Te Ching is (often) experiential. You must find your own way to nonaction, embrace your contrasts, and understand, well, your way. The Tao isn’t a map of an eternal path; you have to walk it through the life you live every day.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

* A note on translations: Translating any ancient text comes with challenges. These include cultural connotations, words with no equivalent, and the quality of manuscripts scholars have to work with. The Tao Te Ching offers an extra layer to these challenges given its terse style and paradoxical leanings.

As such, it’s worth noting that the quotes featured in this article come from Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English’s translation. If you are using a different version, these verses may read strikingly differently, leading you to unique and perhaps contradictory insights. In a way, that’s appropriate. As Lao Tsu writes in his famous opening line: “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.” (Well, that’s one translation anyway.)