Man apparently cured of type 1 diabetes following new stem cell therapy

- Type 1 diabetes results from the body’s inability to produce insulin.

- The apparent cure came from an infusion of stem cells that differentiated into the type of cells the body needs to produce insulin.

- Concerns remain that the patient’s body may reject the foreign cells.

This article was originally published on our sister site, Freethink.

Brian Shelton wept.

He checked his blood sugar, ate a meal with his ex-wife, checked his blood sugar again, and wept.

His insulin levels were perfect. The type 1 diabetes that had caused him to crash his motorcycle, faint in a yard, and forced him to retire from the postal service, was gone.

The diabetes cure was an infusion of stem cells that turned into the type of cells the body needs to produce insulin — cells that had never worked in his life before.

“It’s a whole new life,” Shelton told the New York Times’ Gina Kolata. “It’s like a miracle.”

In just the year before Shelton’s treatment, he had suffered five severe, potentially life-threatening episodes of low blood sugar, USA Today reported.

Now, Shelton’s dramatic results have those in the field cautiously optimistic that Shelton’s stem cell-based procedure could be a cure for diabetes.

The dramatic results have those in the field cautiously optimistic that stem cell-based procedures could be a cure for type 1 diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes: Diabetes comes in two varieties that lead to the same problem: the body cannot keep its blood sugar levels in the right place. In the case of type 2 diabetes, the most common form of the disease, the body does not utilize insulin correctly.

In the case of type 1 diabetes, like Shelton had, the body is wholly missing the cells that create insulin. Called islet cells and found in the pancreas, type 1 diabetes appears to be caused by the immune system wiping them out.

Type 1 diabetes can prove lethal in short order if patients do not receive injections of insulin, and it can cause amputation, kidney transplants, and blindness.

Artificial insulin is the standard treatment, but it can be extremely expensive, and artificial pancreases — which have now been approved for children — can make managing the condition easier, but are not a cure for diabetes.

There is a known type 1 diabetes cure: transplanting islet cells from a donor’s pancreas, or the whole pancreas. But it is far from practical — there just aren’t enough healthy, donated pancreases out there.

Which is why Shelton’s stem cell results have researchers optimistic — but guarded.

“It is a remarkable result,” UCLA diabetes expert Peter Butler, who was not involved in the trial, told Kolata. “To be able to reverse diabetes by giving them back the cells they are missing is comparable to the miracle when insulin was first available 100 years ago.”

To develop the treatment, researchers had to reverse-engineer how the body grows the pancreas to begin with.

A dad vs. diabetes: The stem cell treatment Shelton received this past June is the result of decades of work by biologist Doug Melton, who began work on a cure after his kids developed type 1 diabetes.

Melton looked to embryonic stem cells as a potential diabetes cure. Stem cells have the capability to become any kind of cell — including islet cells. But coaxing them to become functional insulin-producing cells took decades of trial and error.

Melton’s small team had to figure out which chemical signals, in what order, work to create islet cells, Kolata explains; in essence, they needed to reverse-engineer how the body grows the pancreas to begin with.

In 2014, they found it: their stem cell-derived islet cells began producing insulin. They worked as a diabetes cure in rodents. After his company was acquired by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, it was time for the next step: human trials.

Shelton was patient number one.

A cure with a cost: Shelton was infused with the cells, which soon went to work producing insulin and regulating his blood sugar, curing his diabetes. While the results are exciting, aside from the fact it’s only one patient so far, it’s not a silver bullet.

Chief among the concerns is rejection. Just like in an organ transplant, an infusion of embryonic stem cells means Shelton needs to take immune system-suppressing drugs to ensure his body doesn’t attack the foreign cells. Shelton told Kolata the immunosuppressive regimen causes him no issues, so far, and it’s much easier to deal with than not making insulin, but it is something to keep an eye on.

Vertex is also looking to run “future studies using our encapsulated islet cells, which hold the potential to be used without the need for immunosuppression,” Bastiano Sanna, executive VP, said.

The success of a similar technique in Canada is a sign of hope that an outright cure for diabetes may be coming soon.

The study Shelton is involved in is on-going, taking place over five years and enrolling an estimated 17 patients; according to their study listing, Vertex does not expect to complete the study until 2028.

Experts told Kolata that they want to see the results of the trial thus far, which has not yet been peer-reviewed and published. Only further research will suss out if adverse events may arise, or if the treatment is temporary.

Not alone: Shelton’s news comes as a team at the University of British Columbia has announced similar promising results, GEN reports.

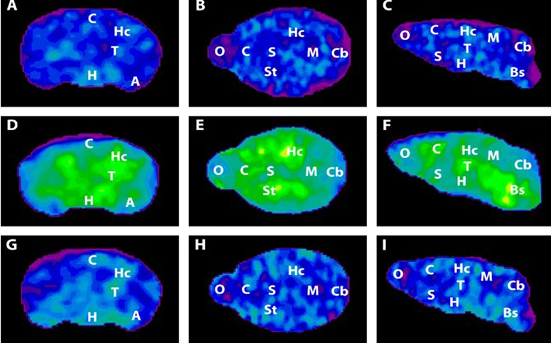

Patients in the Canadian study, which has been published in Cell’s Stem Cell journal, used a different type of stem cell, surgically implanted on small, credit-card thick devices.

“Our findings demonstrate the incredible potential of this stem cell-based treatment. With further research, this treatment could one day eliminate dependence on insulin injections and transform the management of Type 1 diabetes,” UBC professor Timothy Kieffer, the study lead author, said.

While the UBC patients did not produce enough insulin to eliminate their need for it, the follow up period, which lasted up to a year, found that their insulin requirements had decreased by 20%, and they spent 13% more time in their optimal blood sugar window.

Still, the success of a similar technique in Shelton is a sign of hope that an outright cure for diabetes may be coming soon.

When Melton told his family the results, they wept, too.