5 Zen masters and what they taught

- The idea of a Zen master is well known, but not everyone can name one.

- Zen masters have provided insights into the mind and examples of alternative ways of living we can all benefit from.

- Here are five of the greatest Zen masters who have left an impact on the world.

The term “Zen master” is a strange one. There are titles in the various schools of Zen that are close to “master,” but the English term is general and vague. Despite this, many people would still be able to point to a Zen master if they encountered one. Often eccentric, frequently intelligent, and always surprising, Zen masters are living examples of another way of looking at the world and experiencing life.

Here, we consider five Zen masters, what they taught, and how they lived their philosophy.

Bodhidharma

The semi-legendary founder of Zen was an Indian or Persian monk named Bodhidharma, who traveled to China during the 6th century to teach meditation. Early texts on notable Buddhist teachers in China include him and note his dedication to meditation as a method. The stories about him got more complex after he was retroactively crowned the first Zen Patriarch.

While most stories on Bodhidharma were likely written to increase his prestige, the legends around him lay the foundations for the lives of other monks. Upon arriving in southern China, he was asked to lecture on Buddhism to a large crowd. Not wanting to disappoint, he got onto the stage and meditated in front of the crowd for some time before getting up and leaving. At the end of his career, supposedly at the age of 150, he tested his followers to determine if they understood him. He decided that the one who offered no reply understood Buddhism the best.

The centrality of meditation, often called “wall gazing” in the early texts about him, was central to his understanding of Buddhism. Exactly which form of meditation he used is unknown, but it is generally held to be something similar to Zazen — the style of meditation that has come to define Zen practice.

Mazu Daoyi

Mazu Daoyi was a Chinese monk who taught during the Tang Dynasty and invented several teaching techniques that would later become indispensable to many schools of Zen. While his monastery was one of many in Southern China, and his doctrine was generally in line with existing theory, Mazu answered an important practical question facing Zen in the 8th century and set a standard many abbots have striven to reach.

At the time, there was a debate between northern and southern schools about how to reach enlightenment. The northern camp tended to be gradualist, favoring rational reflection on scripture, lots of meditation, and a step-by-step movement toward a true understanding of the world. The southern schools, while still using many northern techniques, argued that enlightenment was a sudden thing that could not be reached step by step. Instead, enlightenment, or “seeing into one’s original nature,” as they often put it, would strike all at once and relied less on rational reflection than intuition.

The southern schools won that round of the debate. However, they failed to answer the question of how to bring sudden enlightenment about. That is where Mazu came in, inventing teaching techniques that eventually became common at certain monasteries. They continue to influence many people’s understanding of Zen.

Hoping to help students overcome the rational part of their minds that often got in the way of enlightenment, Mazu developed shock tactics. He would shout at students, call their names as they left rooms, knock them to the ground, and reply to their questions with nonsensical retorts in hopes of startling them out of their typical mode of consciousness. By showing students that reality was right in front of them and that it had no obligation to satisfy their inquiring, rational minds, he hoped to give them a taste of enlightenment — or dirt, as it sometimes ended up being.

Dōgen

The founder of the Soto school of Japanese Zen, Dogen has been praised as one of the greatest thinkers in Japanese history. Rejecting an aristocratic life to become a monk, he was ordained at the age of 13. Despite learning from many leading figures in 13th-century Japan, he was unsatisfied with Japanese Buddhism as it existed at the time and sought new teachers in China.

Before getting off the boat in China, he encountered the cook of a Zen monastery whose knowledge of Buddhism surpassed his own. Encouraged, Dogen wandered China looking for a teacher and eventually found one in Tiāntóng Rújìng. Like many other great Zen masters, Rujing emphasized meditation, which Dogen took to heart. After reaching enlightenment while studying under Rujing, Dogen returned to Japan to start his own school.

Dogen’s teachings are best shown in his book the Shōbōgenzō. Like many other teachers, he stressed the importance of sitting meditation. He favored shikantaza, a meditation where the sitter is aware of their thoughts but does not interact with them. Doctrinally, he argued for the unity of practice and enlightenment itself, the universality of Buddha-nature, and the combined internal and external nature of virtue.

He also addressed the sudden or gradual enlightenment question by positing that “all who were ever enlightened … practiced Zazen without Zazen and became instantly enlightened.” He suggests that anything can be meditative, that those who achieved seemingly sudden enlightenment were practicing meditation all the time, and that this makes meditation all the more important. This places him closer to the “gradualism” side of the argument as a result.

Ikkyu Sojun

A student of the Rinzai school of Japanese Zen during the 15th century, Ikkyu was introduced to Zen as a child when it was increasingly corrupted by political involvement, commercialization, and a lack of focus. Ikkyu became the great Zen iconoclast and is revered as both saint and blasphemer.

Studying under a difficult abbot in an isolated temple near a lake, Ikkyu meditated at night in a boat. He reached enlightenment suddenly at age 26 after being surprised by a crow. At 46, he was invited to lead a temple, but grew sick of it in a mere ten days.

In a resignation poem, he noted that more Zen could be found in meat, wine, and sex than in the monastery. He would know, given that he regularly broke his monastic vows to indulge in all three and regularly wrote against celibacy. Disturbed by the commercialization, political intrigue, and general failings of the monastery, he left to wander Japan.

He spent the next several decades as a vagabond. This allowed him to interact with people from all levels of Japanese society, write poems critiquing the focus given to poetry in monasteries, and compose prose on Buddhist philosophy. A record of his (mis)adventures can be found in his poetry and in a number of folk tales.

At the end of his life, he was appointed the abbot of a monastery in Kyoto in hopes that he would help rebuild it after the Onin war. Never fully comfortable with this role, he later reflected on it poetically by saying: Fifty years a rustic wanderer, Now Mortified in Purple Robes. He is also remembered for helping to inspire the Zen tea ceremony, his excellent calligraphy, and several ink paintings. His often adult-rated poems are also highly regarded, if not widely read.

Thích Nhất Hạnh

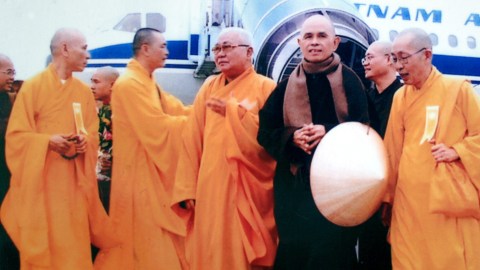

A student of the Thiền school, the Vietnamese interpretation of Zen, Thích Nhất Hạnh was perhaps the second most famous Buddhist monk of the 20th century, after the Dali Lama.

Entering a monastery at the age of 16, Nhất Hạnh was an active man and an eager learner. He left his first Buddhist academy because he felt it did not offer enough coverage of modern, secular subjects. After finding another, he also began taking classes in modern science at Saigon University. Around this time, he began writing, teaching, and taking up anti-war activism. His calls for unifying the various Buddhist organizations in South Vietnam drew the ire of his monastic superiors. His calls for peace led to the South Vietnamese government accusing him of being a communist and of committing treason.

Unable to return to Vietnam until 2005 — the communists didn’t like him either — he settled in France and established the Plum Village Monastery. He lived in France until his final return to Vietnam in 2018. During the decades in between, he became a world-famous activist and teacher.

His teachings form the basis of the Plum Village tradition, which combines ideas from several Buddhist schools and highly emphasizes mindfulness practice. Modern mindfulness practice owes a debt to his 1975 book The Miracle of Mindfulness.

He is also considered the inspiration for “engaged Buddhism,” a term he coined. Engaged Buddhism aims to combine Buddhist practice with social action on many issues. It is increasingly popular, and the Dali Lama has commented favorably on it.