Philosophy of objectification: Why everything changes when someone looks at us

- Jean-Paul Sartre argued that when we are seen by another person, our entire being is wrenched into a public display. We live “for” others instead of ourselves.

- Frantz Fanon made use of this idea in his black existentialism. He argued that black people are fixed in a way white people aren’t.

- Simone de Beauvoir applied it to the female condition. Women are forced to learn they “must” be looked at, and it objectifies them uniquely.

It’s a beautiful day in the park and there’s no one else there besides you. Having a moment, the kind of peculiar turn that all of us have, you begin to skip and sing a childish song. It’s out of tune, and the lyrics are half-remembered nonsense, but you don’t care in the slightest. You’re living a dance of pure joy. It’s a moment that exists between you and the uncaring universe.

Suddenly, you notice there’s a man sitting on the bench up ahead. He’s trying to look away, to save you the embarrassment of his being witness, but you know he’s seen you. He’s seen you in all your insane glory. You turn scarlet. Your dance becomes a respectable walk. You try to hide your song in a cough.

The French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre called this moment The Look. It’s a great introduction to the key ideas of “en-soi” and “pour-soi” — ideas that resonate with most people and are central to the philosophy of race and also feminism.

Living for myself

Sartre’s great work, Being and Nothingness, is a curious mixture of dense philosophical analysis playing alongside hugely readable anecdotes. The book is a trove of ideas, many of which feature heavily in modern sociological commentary. One key element in his work is the distinction between something existing “in-itself” (en-soi) and “for-itself” (pour-soi).

In brief, en-soi refers to all those things that are fixed, passive, and defined. Most often, they are the objects we encounter in the world, from cutlery to gerbils. Pour-soi, though, is our dynamic, personal experience. It’s our awareness directed outward at the world. It’s the “me” that’s doing things and “being.” It’s you, right now, wherever you are, looking out at things.

For Sartre, The Look (sometimes translated as Gaze) is when “The Other” forces us to see ourselves not as pour-soi but en-soi. It is when we, the subject of our life, are made into an object or some background prop. When someone Looks at us, we’re forced to see ourselves as if from outside. As Sartre wrote, “I see myself because somebody sees me.”

Seeing myself through your eyes

Sartre’s idea of The Look is not just about being self-conscious. The Look of another will often go on to create “modifications in my structure.” It changes the entire way we see ourselves. We experience ourselves not as ourselves, but as through another’s eyes.

One huge ramification of this is how we become acutely aware of our body. When we’re alone, our body is something we largely ignore. It’s just an extension of me. When another sees us, though, our body comes into existence as an object. It’s something to be examined and judged — as en-soi.

When this happens, we find we flatten our hair, wipe our mouth, or sit up a bit straighter. We present ourselves rather than live ourselves. We are a feature to be displayed, and our attention (always so resolutely directed outward) comes to look on itself. It’s navel-gazing and self-consciousness, and it’s unavoidably human.

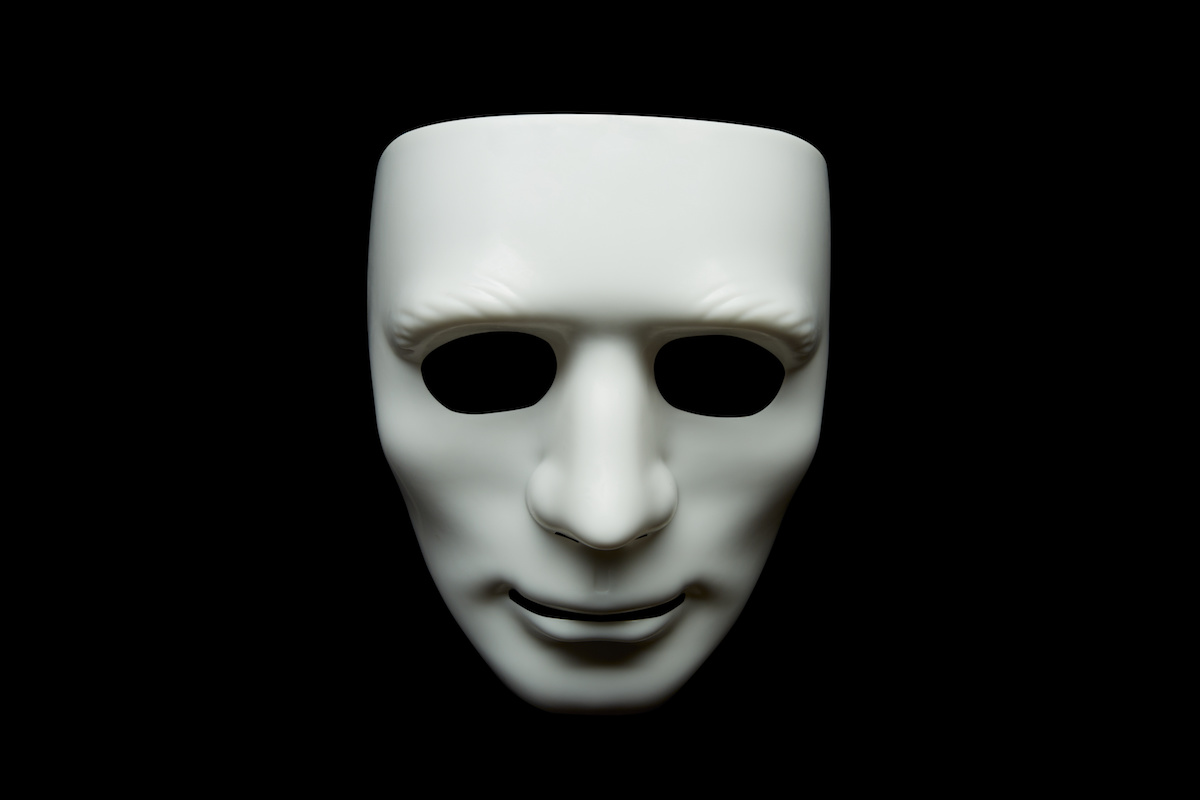

Black skin, white masks

Sartre’s ideas (as well as his frequent public lectures, appearances, and publications) came to dominate so much of the intellectual zeitgeist of post-war Europe. His exploration of The Look has had huge application, in large part because it’s just so relatable. But Sartre’s idea also became a central feature in the philosophy of race.

Frantz Fanon, a French Martinique and black existentialist, revisited and examined the idea of The Look in his book, Black Skin, White Masks. For most white people, the color of their skin is not a feature, but rather the default or norm — born both of biases and centuries of being both a majority and those with power. The black person, though, is made acutely aware of their skin by The Look of others. A black person’s skin color is a feature of their being that it’s not for the white person. As Fanon writes, “When people like me, they like me “in spite of my color.” When they dislike me; they point out that it isn’t because of my color. Either way, I am locked into the infernal circle.”

In many cultures, Blackness is Other. It is alien, abnormal, and minority. The problem, according to Fanon, is that this sense of Other becomes internalized, becoming how people start to see themselves. They are aware of their black skin in a way their white friends or colleagues simply aren’t. As he writes, “As long as the black man is among his own, he will have no occasion, except in minor internal conflicts, to experience his being through others.” However, being constantly seen as black goes to fix and trap the subject (our pour-soi) in objecthood (en-soi) — but also an inferior, lesser one. He goes on to write, “I sit down at the fire and I become aware of my uniform. I had not seen it. It is indeed ugly. I stop there, for who can tell me what beauty is?”

Sexual objects

Working and writing parallel to Sartre (as well as inspiring, editing, and likely developing his ideas) was Simone de Beauvoir. The idea of The Look features heavily in her great feminist work, The Second Sex.

In her sections on Childhood and The Girl, de Beauvoir argues that early on in a woman’s life they learn that their role is to be watched. They are to be ogled, judged, chosen, and eventually taken by a man. It’s a cruel and terrifying moment in a young girl’s development, when sometime around puberty she realises that she no longer exists as a person in herself, but as an object to be seen. As de Beauvoir writes, “The [pubescent] girl feels that her body is escaping her, that it is no longer the clear expression of her individuality; it becomes foreign to her; and at the same moment, she is grasped by others as a thing: on the street, eyes follow her, her body is subject to comments; she would like to become invisible; she is afraid of becoming flesh and afraid to show her flesh.” (My emphasis.)

De Beauvoir goes on to argue that the issue is confused further in how women come to accept “being looked at” is their lot. At this point, she writes, some women seek and even enjoy attracting The Look of others — but only in a way that preserves an element of them. Most women can easily tell the difference between a look and The Look. The former is something relatively benign, something (de Beauvoir argues) women even want.

But the latter is much more pernicious. It’s an invasive, predatory, objectifying, and leering thing. It’s both scary and dehumanizing. As she writes, “[the girl] would only like to be seen to the extent that she shows herself: [but] eyes are always too penetrating… masculine desire is an offense as much as a tribute.”

The Look is everywhere

The Look is something that alienates, judges and reduces minorities or prejudiced groups worldwide. But it’s also something we all know and can appreciate. It’s the shame of being spotted doing something silly, crude, or wrong. It’s the self-consciousness of being judged and then judging ourselves. It’s the moment when we stop living life as we want to and start living it to the tune of another.

The Look is where our private self is dragged into a public domain to be examined and fixed. It’s when we appreciate that the eyes are far more powerful than we ever knew.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.