Read this book if you want to understand what drives inventors, engineers, and scientists

- Inventors may be inherently gifted, but they generally require the right circumstances to produce brilliant results.

- They usually “sign up,” implicitly sacrificing part of their lives.

- The Soul of a New Machine presents a realistic look at what drives their world, made enjoyable by a compelling story.

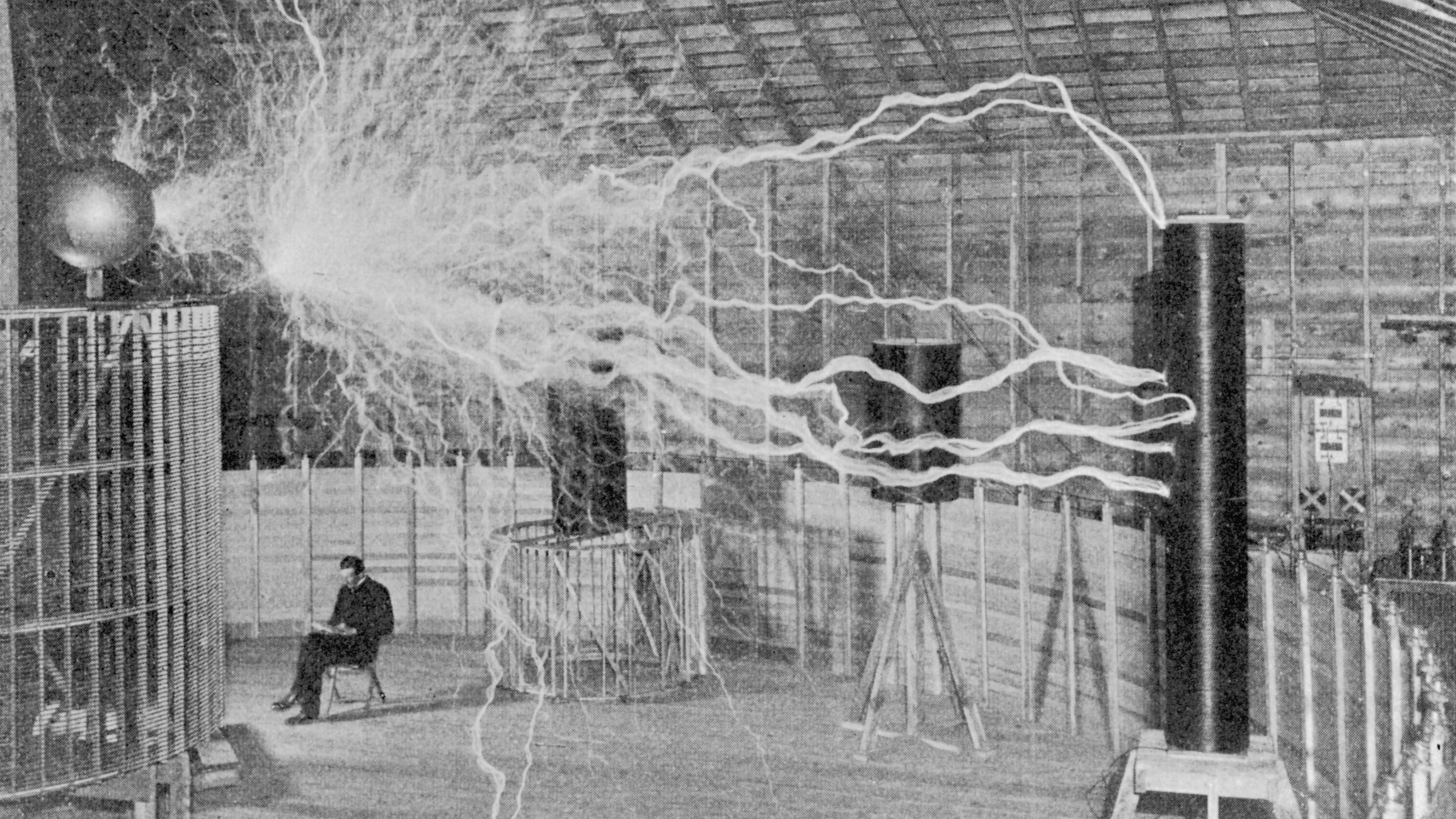

Did Nikola Tesla dream up wireless power because cogitating in front of a giant coil scrambled his brain? What inspired Einstein to imagine riding a light beam? The spark of intuition is a sexy idea, but it’s a woefully incomplete understanding of the accomplishments of researchers and inventors. What conditions drive their success? What mentality must they adopt? How does the greater creative process, beyond the elusive stroke of genius, work?

The Soul of a New Machine provides a rare level of insight into these questions. Much like The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a reader who has lived in the world it describes immediately recognizes truth in its observations. While Tracy Kidder’s story follows a group of computer engineers, it could just as well describe the work of many groups of research scientists, tech innovators, and other pioneers. While it points out the golden moment of a new idea, the book’s forte is living inside the lengthy struggle of invention, empirically discovering its nature.

The book’s foremost observation is the ritual of signing up. Nearly everyone who has chased the dream of producing cutting edge research or technology has faced this reality (or taken the blue pill and quit). Kidder provides a neat definition: “By signing up for the project you agreed to do whatever was necessary for success. You agreed to forsake, if necessary, family, hobbies and friends—if you had any of these left (and you might not if you had signed up too many times before).” Throughout the story various people encounter their moment of decision: will they sign up and give over their lives (or walk away, to live on a commune in Vermont)?

This concept defines not only the personal lives of these (mostly) men, but the spirit behind their labor. Even after you’ve signed up, you’re not being forced to neglect your outside life. You do it willingly because you accepted the deal in order to accomplish something new at all costs. You feel internally compelled to work in a windowless basement, far into your nights and weekends. This concept is foreign to the 9-5 worker who ducks out early on Fridays. It’s usually also the required price of success, or a shot at it, in the competitive and difficult effort to birth something new, beyond the horizon of what is known. Rarely do 9-5 workers beat people who’ve signed up.

Those who sign up aren’t paid overtime; they aren’t doing it for the money. Upon closer study, it appears they’re driven by being where the action is. When (if) they succeed in some extremely hard project, they get the chance to be a part of the next extreme effort to build something entirely new. They get to stay out on the edge. The book describes this with the (somewhat archaic) metaphor of getting the chance to play pinball: as long as you win you get to keep playing.

It’s clear that this game is for the young. The managers of the team are mostly in their early thirties; the men who sign up for the action are in their twenties. They want to get it on the big chance to do something new, rather than grinding out rote 9-5 work that bores them. All of them want to stay at the pinball controls. However, after the all-consuming battle is finished, most of the older men move on to other work.

A clever manager is the story’s unusual protagonist. He shields, manipulates, and shuns his men. As a result, the team believes that the heart of the machine is created solely from their ideas and gumption. It takes form only by their labor and hardship. Our protagonist never takes the team’s side: he appears as one of many obstacles arrayed against them. The team must fight competitors around the world and within their own company. The work is somehow both crucial and unsupported. The managers mockingly dub this mushroom management: “keep ‘em in the dark, feed ‘em s(tuff), and watch ‘em grow.” And yet it’s simply a crusade, a motivation as old as time.

Revelations about the clever manager lend the story a sweet and thoughtful conclusion. He silently supports the team in ways they never see. This gives him the feel of a genius, a picture the book strives to paint. Yet, what portion of their success is foresight and what portion is jumping in blind and catching a few breaks? What part is talent blossoming under excellent leadership, and what part is working beyond exhaustion and distorting reality? In some places there is a great deal of guiding instinct and intelligence behind the difficulty and chaos. In others there may be only chaos.

The Soul of a New Machine integrates these ideas into a compelling and enjoyable story of people. Kidder peppers the work with humorous jargon and technical background, but it’s subsidiary. The greater point is the suspense of the struggling project and the stories of the sympathetic engineers, straining to produce something from nothing on a ludicrous timeline. Read it to understand and visit the real conditions that incubate breakthroughs in engineering, science, and invention.